Warren Feeney – 22 September, 2011

As the final exhibition at 183 Milton Street, Charlotte Watson's Exurbia seemed particularly appropriate. Working with discarded kitchen planks and joinery, cut and shaped to form interlocking models of make-shift buildings, Watson encouraged visitors to construct minimalist, architectural sculptures on the lawn in the backyard.

Christchurch

Charlotte Watson

Exurbia

5 September - 2 October 2011

Charlotte Watson’s Exurbia at 183 Milton Street in Sydenham is the last exhibition in a series curated by forth-year sculpture student Tim Middleton who, for the past nine months, has provided senior students at the University of Canterbury with the opportunity to exhibit in his home. His decision to open it as a gallery was born of necessity in response to the absence of exhibition spaces at the School of Fine Arts at Ilam immediately after 22 February.

Watson’s sculptures and drawings are the seventh exhibition and like all previous shows, it has been held without incurring any of the costs of gallery administration, curator fees, light, heating or catering. Neither has it received funding from central or local government. It would be tempting to argue that Middleton has proved the truism that artists will always find places to make and exhibit work - whatever the circumstances. And yes, there is an element of fact in such claims. 183 Milton Street has maintained a consistently high quality of work and provided enough moments of surprise and pleasure in its programme to make it easily comparable with the best artist-run spaces in the country. And all achieved without the support structures, Boards of Trustees, funding or sponsorship that is assumed necessary for the success of such well-established institutions.

Indeed, 183 Milton Street arguably represents an empowering example to artists anywhere in the world - a gallery which has risen above the realities of filling out endless funding application forms to manage and maintain an autonomous arts institution. Yet, although that’s a valid moral position to take, the reality of the current closure in Christchurch of its public art gallery, SOFA, the Physics Room, COCA Gallery, Brooke Gifford, Salamander Gallery, The National, Form Gallery, etc, etc, all suggest that the majority of the arts community would never wish the necessity for spaces like 183 Milton Street on any artist or arts community.

Middleton has made a virtue of challenging circumstances in a gallery space that has been conceived to respond to immediate needs. Whether he wished to or not, however, his home-as-gallery has also turned attention away from familiar models of the art gallery. 183 Milton Street is neither a traditional artists-run space or dealer gallery and public gallery. Rather, it is site-specifically domestic with Middleton’s home acting as installation and environment.

Moreover, if Middleton had selected an average to good series of shows, 183 Milton Street might have only been an admirable project. However, he has chosen the work of colleagues he admires and engages with in daily conversation and debate. The selection process for exhibitions has evolves from discussions between Middleton and fellow students, rather than a curatorial panel, advisory group or board. A connection exists between the artist as maker and the gallery as institution that is not typical of gallery/museum practice in general. The success of 183 Milton Street’s programme resides, not so much in that it demonstrates that artists will continue to make work in difficult circumstances, but in the example it provides to galleries and arts institutions throughout the country to allow practicing artists to become a greater part of the decision making about the shape and relevance of a gallery’s exhibition programme and to provide a more influential role to the artist as stakeholder in such institutions.

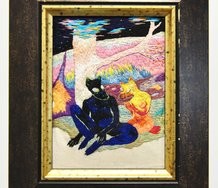

As the final exhibition at 183 Milton Street, Charlotte Watson’s Exurbia seemed particularly appropriate. Working with discarded kitchen planks and joinery, cut and shaped to form interlocking models of make-shift buildings, Watson encouraged visitors to construct minimalist, architectural sculptures on the lawn in the backyard. The gesture of giving over the decision making to the community seemed to ironically comment on the Christchurch City Council’s current request for its residents to contribute to the strategic plan for the rebuild of the inner city. It also seemed a somewhat detached, yet poignant reflection on the kinds of structures being assembled at present throughout Christchurch. The simple, architectural shapes that transpired in Exurbia from the community of artists, family, friends and children that assembled them, appeared as though they may had been formed from the outdoor sundeck that they sat next to. This was art made in suburbia on a scale appropriate to circumstances. It sincerely acknowledged the importance of community and the value of the conversations that artists contribute to everyone’s neighbourhood, but also quietly subverted such a premise as a work constructed on the outer edges of a doughnut city - the artist potentially confined to the margin in almost every sense of the word.

Warren Feeney

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.