Erin Driessen – 25 May, 2012

The black paint was directly poured onto certain works, like 'untitled (flower painting)', so that it blended with the original work and created an even surface. For others, like 'Tukituki River and the Craggy Ranges (Hawke's Bay)', Kennedy made the black patches first by pouring house paint onto sheets of glass. The patches were then laid onto the surfaces of the found objects. These works oddly attain a sculptural presence, as the fabricated holes, are in no sense voids.

Dunedin

Alexandra Kennedy

New Voids: An Exhibition of Interventions with Found Objects

12 May - 3 June, 2012

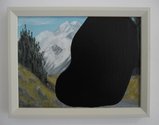

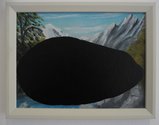

An exhibition of seemingly conventional, uniform landscape paintings is an unexpected site at A Gallery. However, the ideas behind the work of Alexandra Kennedy easily explain the place of New Voids here. Kennedy spent nine months hunting through secondhand shops and garage sales for old paintings. One is a still life - the only hint is in the title, untitled (flower painting) - and the rest are landscapes. She has painted black ‘voids’ onto the surface of each, except for untitled (river and bush) and untitled (river and bridge), whose voids are blue and green respectively.

The black paint was directly poured onto certain works, like untitled (flower painting), so that it blended with the original work and created an even surface. For others, like Tukituki River and the Craggy Ranges (Hawke’s Bay), Kennedy made the black patches first by pouring house paint onto sheets of glass. The patches were then laid onto the surfaces of the found objects. Apparently, they will peel off the paintings and retain their substance, an idea I found quite appealing as I imagined the artist taking the work further, using other objects in conjunction with these thick, tactile additions. These works oddly attain a sculptural presence, as the fabricated holes, like artist Carl Andre’s, are in no sense voids. They ooze out of the original works, or they retreat into them, digging and filling simultaneously.

These plays on perspective speak to Kennedy’s artistic outlook on space. Her work references Russian Suprematism, as well as concepts of the zero gesture, anti-gravity and cosmic space. Kennedy’s work is cynical and almost nihilistic, while its self-referential and circular nature functions dialectically as painting about painting. There is something ominous in the black globs that seem to expand and float, threatening to engulf the gallery space. With regards to the subject matter of the paintings, Kennedy adopts a sardonic attitude towards rhetoric surrounding environmental sustainability and resource consumption.

In untitled (river and bush) and untitled (river and bridge), Kennedy has shaped the blue and green blobs in relation to the curvatures of the landscape in each painting. The blue of the former flows from the bank into the river; the green of the latter follows the tree line and covers all signs of the bridge. Some of the black holes in other works float in the middle, the surrounding landscape clearly visible, while others cover most of the original painting. The choice of landscape paintings could mean many things - New Zealand, a common and conventional form of amateur art, or environmental connotations.

Kennedy is also interested themes of anti-pursuit, destruction, and voids. The expression of these concepts in art is not new. Artist Sol Le Witt buried cubes underground during the sixties, acts which begged the question “Is it there if you can’t see it?” Le Witt would respond, “Does it matter as long as you’re thinking about it?” Then there were artworks which only achieved meaning once they were destroyed, either by the artist or by natural forces like gravity or erosion. They only became artworks not once their objectness was permanent, but when it was irreversibly made invisible. Artist Robert Barry once said, “Nothing seems to me the most potent thing in the world.”

The sixties also bred a strong artistic reaction to the very presence of objects, something which Kennedy feels strongly about. The idea that there are already enough objects in the world, so why make more, fueled much conceptual art. Kennedy’s work cannot be counted as conceptual art, yet its preoccupation with the readymade and non-Euclidean spatial concepts places its inspiration in that art-culture-shifting milieu. Her work seeks to nullify through adding, to disappear through painting. Figurative convention is overcome by nonobjective abstraction.

The choice of landscape is an interesting one to me. An important part of Kennedy’s process was finding that she did recognise these found objects as works of art as well. Readymades are usually explicitly non-art objects placed within an artistic context. How strongly did the subject matter determine the shape or placement of the ‘voids’? If the artist allows the found object to determine the end point, is her objective most evident in concept or process, or final product? Kennedy expressed the idea of “grey goo” consuming the world. Are these orbs that goo in artistic form? Or is the self-replicating whiteness of the gallery a consumptive space; is the white cube really a black hole?

Kennedy’s interventions (or perhaps it is all one intervention, a painting gestalt) are interesting in the proponents they conjure, from Duchamp and Malevich to Kaprow and Huebler. The work in New Voids seems more about process and concept than aesthetic, yet the substance of the voids lends them object status. Kennedy occupies the space between painting and sculpture, and her work carries forward ideas that challenge conventional notions of art process.

Erin Driessen

Recent Comments

Owen Pratt

perhaps dangerously under thinking it there Andrew, the connection between this work and RL Stevensons' 'Treasure Island' seems glaring to ...

Andrew Paul Wood

Meh. You're over thinking it. I doubt it's any deeper than this: http://www.slate.com/slideshows/arts/put-a-monster-on-it.html

Andrew Paul Wood

Ultimately it's origins may well lie in land art intervention http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5AmpyiR6kj8

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 8 comments.

Comment

John Hurrell, 9:07 a.m. 25 May, 2012 #

These seem to be a conceptual hybrid between Tony de Lautour's Revisionist Paintings and Layla Rudneva-Mackay's'blanket' or 'towel' photographs that hide the scenery and person holding the fabric up.

Maybe they are more like Christian Capurro. http://www.eyecontactsite.com/2010/10/something-happened

Erin Driessen, 12:10 p.m. 25 May, 2012 #

I think these are really interesting connections, thanks John. They all say something about the process of interruption and how it can in turn be viewed as continuance or addition.

Tim Nees, 9:24 p.m. 25 May, 2012 #

These works lack the paranoid brittleness of de Latour, the impolite. Or the self-conscious academic-ness of Rudneva-Mackay. The studiousness. It is easy to look at (the reproductions of) these small framed object-images and be intrigued/attracted/seduced. It's easy to imagine the curving hand that guided them, the tip and fall, the slow slide of paint upon the land.

They are considered and polite, and attractive. Beckoning. They are asking to be liked. And rather than negate the landscape, they appear to activate it in much the same way Binney's curvaceous birds capture our attention and ask us to 'look first at me' before we make our way through the land. True, in some the area left to explore has been pushed to the margins by the swollen voids, which makes the amateur brushstrokes as captivating as the texture of the poured paint. Perhaps the overlay holds the landscape rather than hides it - a pause rather than a void, an action slowed to stasis - and caresses the canvas as spilt oil caresses the garage floor.

I'm also of course reminded of the recent 'unfolded landscape' works of Kate Woods, though she has a more alien-interventionist approach, the sci-fi nip and tuck, whereas Kennedy's lineage perhaps is earthier and connects back to Charles Brasch and Landfall and Dunedin and Tekapo and all those creative nationalists who tirelessly tramped through the NZ bush and scaled the peaks drinking rough red wine and flat beer and blessed the spirits that placed them in this place.

Nostalgia takes comfort, here.

John Hurrell, 8:16 a.m. 26 May, 2012 #

If I were a 'Sunday' painter and found one of my endeavours in a gallery with black paint poured over it I'd be extremely upset. I'd see it as a spiteful act of aggression, not 'considered...polite, and attractive.' I'd take it really personally.

Josh O'Rourke, 5:32 p.m. 26 May, 2012 #

Perhaps the artist is reusing these paintings in an act of appreciation, not "a spiteful act of aggression"? Possibly the artist has a 'guilty pleasure' for this style of work, and is paying a form of respect by re appropriating it in this context.

Andrew Paul Wood, 12:55 a.m. 27 May, 2012 #

Meh. You're over thinking it. I doubt it's any deeper than this:

http://www.slate.com/slideshows/arts/put-a-monster-on-it.html

Owen Pratt, 10:18 a.m. 28 May, 2012 #

perhaps dangerously under thinking it there Andrew, the connection between this work and RL Stevensons' 'Treasure Island' seems glaring to me but. When Long John Silver is given the 'black spot' by Blind Pew the curse is reversed when Silver notices the glyph is marked on the text of a bible. Arrr.

The black spot, the sacred and profane (landscape / Sunday painter) the generic curse of being a painter in 21C and the ideas of buried treasure as a rich reward for cultural effort are all present here. Arrr.

Andrew Paul Wood, 12:51 a.m. 27 May, 2012 #

Ultimately it's origins may well lie in land art intervention http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5AmpyiR6kj8

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.