John Hurrell – 25 June, 2012

Much is hidden underground, especially to ensure the stability of spectacular sculpture by artists like Anish Kapoor, Richard Serra, Neil Dawson and Bernar Venet. And even a ‘surface' work like the meandering Buren fence is complicated, with some sections devoid of strands of horizontal wire and hundreds of green and white striped posts perfectly aligned on a north-south axis.

This sculpture park is internationally legendary, and it doesn’t take too long to grasp why - with its gorgeous Kaipara harbour setting and impeccably manicured rolling downs with ridges perfect for silhouetting dramatic works of art. The massive size of the most of the art, and the pedigree of its eighteen creators make this unusual venue essential viewing for serious art lovers. Aucklanders are incredibly lucky to have it so close.

The website is extremely informative - with an excellently informative Rob Garrett article and a bunch of wonderful videos - but as the displays keep changing it is probably always a little out of date. There don’t seem to be Oursler, Orr, Booth, Hotere, Reynolds, Culbert or Roche sculptures now, though perhaps they still exist and Gibbs shows them privately to visitors at night (most of these are light based). Instead there are Venet, Lin, and Thomson displays - works very conspicuous in daylight hours.

When I came with my friend Marian last Thursday, we were incredibly lucky with the weather. It was almost perfect - not too hot for walking and yet not liable to leave you soaked. We thought maybe there might be two or three other cars calling in, but in reality there was a constant stream of visitors within the restricted hours of 10 to 2. I counted at one stage over fifty parked cars and two coaches.

That means that as the roads are placed high up near the ridges you see a lot of walking figures like yourself, inadvertently competing with the sculpture. Traipsing people collectively become another artwork on the skyline.

Not only is the Farm spectacular evidence of Gibbs’ tenacity as a commissioning, self-funding curator (his conversations with these artists finalising their projects can go on for several years) but the foundation-making, engineering and landscaping aspects are phenomenal. Much is hidden underground, especially to ensure the stability of spectacular sculpture by artists like Anish Kapoor, Richard Serra, Neil Dawson and Bernar Venet. And even a ‘surface’ work like the meandering Buren fence is complicated, with some sections devoid of strands of horizontal wire and hundreds of green and white striped posts perfectly aligned on a north-south axis.

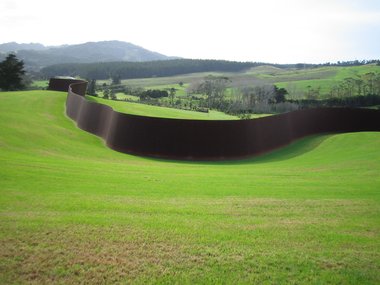

My favourite works are by Serra, Buren and Wang. The Serra alone is worth a pilgrimage. Considering it is made of 56 joined steel plates, each 20 feet high and 2 inches thick, it has a surprisingly soft, delicate, ribbonlike sensitivity along its upper edge - seen only from above. From below, other parts exude a frightening and brutal power, as if it were a swelling dam about to burst.

One surprise is that Buren’s work is rich in humour. From the distance it looks like an impassable electric fence, yet because some portions are only posts, it misleads visitors when they plan to circumnavigate seemingly obstructed fields to reach sculptures on the other side.

The Zhan Wang sculpture, protruding from a pond, is also mischievous. It looks like a pointed rock, painted chrome. It is actually a floating hollow steel form that seems geological - with vaguely human shapes embedded in it. The wind allows it to turn very slowly, anchored in its centre.

Some works are so big they become gross. There is something repugnant - almost strutty and aggressive - about the Kapoor and Venet projects, although it is more the lurid fleshy colour of the taut Kapoor that disturbs. While their complexity gives out a lot (the Venet uses language and mathematics to prod the imagination) they really dominate to an excessive degree. The Serra and Wang in contrast seem delicate - the way they sit in the land. They beguile with nuance.

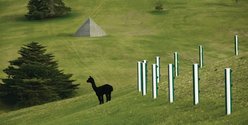

Several sculptures, like those of Wang, Lye and Rickey, use motion, as does an underwater fountain that squirts planar configurations into the sky - possibly designed by Gibbs himself. The other moving element is the livestock. Flocks of moving sheep activate the zones between the sculptures, as do unusually sculptural beasts like ostriches, giraffe, llamas, shaggy haired Scottish cattle, dark brooding yaks and long-horned buffalo. Their odd shapes and grazing patterns really contribute to the ambience because they usually stand out in high contrast to the carefully mown grass.

With this art collection the main aspect as you move around is the shrewd placement of work within the undulating rolling hills. Bizarre forms abruptly pop up, peeking at you from over distant ridges. The Lye Wind Wand suddenly seems to be chatting to the red lipped Kapoor. Spatial distance becomes compressed.

While the aerial photograph on the website suggests that the Gibbs Farm is so immense that four hours visiting might be too brief a period, once there you realise the venue is cohesive, compact and walkable. It doesn’t take too long to see 70% of the works - about two and half hours. In our case, after three and half hours we had seen all but three sculptures at close hand, and as rain was starting to set in, it was time to leave.

However these are the sort of works you need to visit several times in different weathers, walking different trajectories and experiencing different seasons. That way you become familiar with their individual characteristics and the quirks of the surrounding landscape and its vegetation. You really do pinch yourself when you encounter such a stunning, hyper-ambitious collection, your visit taking on a dreamlike quality. For our part of the world it is so unexpected.

John Hurrell

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.