Warren Feeney – 26 July, 2012

There is a shared modesty of scale and a mutual paring back of imagery that renders these works smart, skilful and rich in potential narratives. Equally, there's a welcome degree of self-depreciation in the telling of stories, revealing a pleasure in making art - and also in associating oneself with the great traditions of the same.

Is a group exhibition by six post-graduates from the School of Fine Arts in Christchurch a great idea or a curatorial problem? This was an issue raised in April this year in the annual exhibition of post-graduate work at the SFA Gallery by curators Barbara Garrie and Chloe Geoghagen. In their introductory note to the show, Master Plan, they challenged the premise that the participating artists had good reason to be in the same exhibition space with one another: ‘In focusing on a given group of artists who have studied at the same institution…. these exhibitions often showcase a disparate range of concerns and approaches within the artists’ own professional practices.’

It may only be coincidence but Mea Culpa, a group exhibition curated by Senior Lecturer in Painting at the SFA, Roger Boyce, could be perceived to be taking up the challenge laid down by Master Plan. In its title, Boyce seems to be pleased to declare that this exhibition is all his fault and yes, he argues, it is possible to put together a coherent and empathetic body of work by post-graduates and place them within the same room.

A cynic might argue that the title of the show, Mea Culpa, simply side steps the problems of group exhibitions, acting as a generalised statement that allows the work of the participating artists to sit together - for whatever reason. The essay by Andrew Paul Wood in the exhibition catalogue suggests this may be so, describing Mea Culpa as a show that ‘brings together a diverse range of skilled and talented artists with varied approaches to the problem of how to make art.’ Yet, I remained unconvinced by such claims. Works in Mea Culpa by Matt Akehurst, Julia Croucher, Adrienne Millwood, Sophie Scott, Rosa Scott and Emily Hartley-Skudder establish warm and intelligent conversations with one another.

At the very least, these artists all share a respect and interest in one another’s work. There is also a shared modesty of scale and a mutual paring back of imagery that renders these works smart, skilful and rich in potential narratives. Equally, there’s a welcome degree of self-depreciation in the telling of stories in Mea Culpa, revealing a pleasure in making art - and also in associating oneself with the great traditions of the same.

So claims that these artists make works, typified by ironic commentary seem questionable. Does a knowing art historical or literary reference merely play to and flatter an audience - as Wood implies - or is it capable of something else? Mea Culpa seems to be about something else. One of the pleasures of this show is the appropriation of images by artists who reveal their affection for - and connection to - source material rather than considering it as simply evidence for a deconstructing narrative. Emily Hartley-Skudder ‘s Vanitas with Candlestick and Yellow Skull takes a painting genre fixated upon the meaninglessness of life to somewhere else and back again. The sweetness of her Vanitas painting, the larger than life colours and sense of unreality, is all the more poignant in its commentary on the brevity of childhood as it reconstructs a memory better than the reality it recalls.

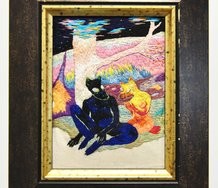

Millwood’s Tracksuit appears as a larger-than-life Kodak slide transparency from childhood, an ephemeral projected image. Millwood’s iconography is nicely poised between figuration and abstraction. Where an artist such as Kate Woods had dealt with similarly ambiguous relationships, Millwood seems less distanced from her subjects - these are organic, intimate images that encourage empathy, recognition and a sharing of memories and values.

This precarious balancing act between formalism and story telling is also shared by Rosa Scott and Julia Croucher. In Seek, Scott plays on a tension between the potential drama of an image and her command of materials and surfaces, while Julia Croucher assembles a summary form on a work on paper in which the figure appears to only just transpire from its surface. The economy of subject in Figure Study 6 only serves to heighten its erotic charge.

Sophie Scott’s Ghost Ship 1 and Ghost Ship 2 similarly reveals or allude to the detail of their subject through absence. Cutting complementary shapes from a cargo ship photograph in identical images - the void of one implicitly transpires in the other. This is a considered image; travel, transport and the premise of building and constructing - the machinations of civilisation in progress and the transient nature of such activity.

Matt Akehurst’s Object 15 could have been conceived from an assembly kit for do-it-yourself modernism. A work waiting to dry before parading itself in a gallery and a bit-player in a Henry Moore retrospective exhibition, as well as an object that wishes for more than it will achieve. Object 15 is an art work that encompasses innocence and the gravitas of its own world weariness, and in this sense, it directs attention to the ‘something else’ that inhabits Mea Culpa. All these artists have chosen their iconography well, assembling evocative storylines that offer the promise of resolution but deliver something far more engaging as oblique and authoritative narratives.

Warren Feeney

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.