Warren Feeney – 19 October, 2012

Working on the notion that New Zealand's most popular painting - as voted on in a television arts programme back in 2006 - is currently inaccessible to the public, Angus' painting of Cass is evident in this show only by proxy, a projected image of Cass on the storage racks at the public gallery accompanied by a checkerboard of additional images that remind the gallery visitor of the numerous ways in which it is considered and valued.

Christchurch

Andre Hemer

Cass Negated

29 September - 21 October

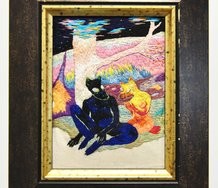

Andre Hemer’s Cass Negated [readers, the name Cass has a bar through it, something this site can’t format - Ed.] is seriously haunting. A blurry, out of focussed spray painted image, Cass Negated is something that looks like it might be Rita Angus’ all-too-famous painting of almost the same name in the act of both transpiring and dematerialising. It is a work that offers a new-found appreciation of Hemer, an artist primarily recognised for his spirited optimism and wit. Cass Negated brings a welcome gravitas and weightiness to Hemer’s practice and a wisdom that strangely enough, now seems to have always been there, just waiting to escape the surfaces of the computer-designed explosions and exclamation marks more readily associated with his painting.

Cass Negated is also a notable exhibition for other reasons. Why did it continue to nag and frustrate me for many days after leaving the gallery? - I loved the Hemer painting, yet this also felt like an exhibition that represented a benchmark for current ideology in arts practice - evidence of the kinds of things that curators and public galleries love to do in the early decades of the 21st century - An exhibition about the exhibition of a painting that includes a painting about that painting? Less generously, Cass Negated might also be considered an exhibition poised between art-world navel gazing and the warm glowing presence of a work that just happens to bring new revelations about an artist’s work.

And it should also be noted that this exhibition is not alone in its self-conscious interest in displaying the tasks, processes and contexts for revealing ways to consider works of art. It’s an idea previously evident in the Christchurch Art Gallery’s curation of Neil Pardington’s The Vault, (2010), an exhibition of behind-the-scenes photographs of artworks in storage and in Fragments, Stories, Myths. The Lives of Lost Art Works an exhibition at the School of Fine Arts Gallery in Christchurch in 2011, which drew attention to the histories and stories that surround works of art. Like Cass Negated, The Lives of Lost Art did not feature the art works that formed the subject of the exhibition. (Okay, they had all been destroyed or lost, but the premise remains.)

Cass Negated the exhibition, demonstrates a fascination with the tasks, processes and duties, undertaken as the core business of an art gallery. So when did the art world begin to assume that its audiences might be interested in what it does from 9 to 5pm? Certainly, the agendas of galleries more than a generation ago in New Zealand could not be more different than the one that Cass embraces. As Athol McCredie documented in his thesis, Going Public: New Zealand Art Museums in the 1970s (Massey University 1999), the first signs of an emerging arts professional, (evident in newly established galleries such as the Dowse Art Gallery, the Govett-Brewster and Manawatu Art Gallery), was all about community involvement, innovative programmes and often political activism. And without wishing to descend to the premise of a fondly remembered ‘golden age’ when galleries remained focussed on direct - often confrontational - engagement with audiences, I remain to be convinced that exhibitions founded upon the tasks and processes in which the art gallery operates and fulfils its objectives, is a great starting point for a curatorial premise.

Working on the notion that New Zealand’s most popular painting - as voted on in a television arts programme back in 2006 - is currently inaccessible to the public, Angus’ painting of Cass is evident in this show only by proxy, a projected image of Cass on the storage racks at the public gallery accompanied by a checkerboard of additional images that remind the gallery visitor of the numerous ways in which it is considered and valued: A projected image of a photograph of Cass by Peter Peryer, an image of Julian Dashper’s appropriation of Angus’ painting, and digitally manipulated projections by Hemer of Cass, all assembled on a single wall in a clustered, checkerboard format at an opposing distance from Hemer’s painting.

I love the dichotomy. One wall of the gallery given over to art history, museum and gallery practice and the visual conversations and appropriations of the art world - and almost in opposition, Hemer offers the viewer this other experience - the silence and singular moment with the work of art - no texts, no labels, just the contemplation of the painted object.

In the discreteness of its hanging and the generosity of space it occupies, Hemer’s Cass Negated seems like a critique on the bustle of activity assembled at the other end of the gallery. It is difficult not to consider this painting, acting in response, with its subject poised to both materialise and disappear. It assumes the guise of a romantic, P. B. Shelley moment - all is vanity: ‘Look on my works, ye Mighty, and despair.’ To his credit, Hemer nicely reconfigures the best intentions of this exhibition, engaging the gallery visitor with a profound and touching reminder about the value of the first-hand experience that an audience has with a work of art.

Warren Feeney

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.