Warren Feeney – 13 August, 2013

There is a clarity and subtlety that gives credence to an exhibition that lets the artworks themselves do most of the communicating. Nga Toi - Arts Te Papa can be consumed and experienced without you necessarily feeling compelled to read the curatorial commentary on the wall as you enter the gallery. Yet the texts provided for each section, in the form of A5 handouts, are valuable, serving to extend the context and detail of the works on exhibition.

Wellington

Collection regrouping

Nga Toi - Arts Te Papa

Ongoing

The re-hang of the permanent collection at Te Papa Tongarewa remains it seems the most consistently satisfying exhibition in Wellington since it opened in April this year. The expanded exhibition space on the 5th floor, addressing long-overdue display issues around that site (as a very long corridor with artworks on the wall) has undoubtedly made a difference - as has the commitment to more regularly changing sections.

This week saw the entrance space altered once again. Warhol Aotearoa brought together - maybe a little too obviously - works by Peter Stichbury, Reuben Paterson and Gavin Hipkins. At the very least Te Papa is delivering on its promise.

Critical to the revitalisation of this institution’s permanent collection is its success in addressing the fundamentals of curating an exhibition. Thoughtful relationships between works of art considered as objects and ideas, rule supreme. There is a clarity and subtlety that gives credence to an exhibition that lets the artworks themselves do most of the communicating. Nga Toi - Arts Te Papa can be consumed and experienced without you necessarily feeling compelled to read the curatorial commentary on the wall as you enter the gallery. Yet the texts provided for each section, in the form of A5 handouts, are valuable, serving to extend the context and detail of the works on exhibition. Well known art historians and arts commentators have contributed short essays. The best are: Francis Pound on Gordon Walters; Rebecca Rice on 19th landscape; Mark Stocker on modernism.

What makes the new presentation worth revisiting is the way in which it surprises despite being a national collection that encompasses so many familiar works. Supposedly representing the ‘best’ of the country’s art, such an agenda has the potential to be a burden; well worn phrases like ‘national identity’ have surely had their moment. And while there are many familiar images (Gordon Walters’ Koru series, Don Binney’s bird paintings or Petrus van der Velden’s Otira Gorge series), be prepared to be enlightened anew.

Gordon Walters’ Koru series in the section titled, Artist in Focus, encompasses drawings, prints, paintings and reproductions in publications that celebrate the broader context of the artist’s work and its status as both design and fine art. In works like Painting No. 7 (1965) there is a regard for him as an international modernist, qualified by the inclusion of reproductions of his work in local journals like Landfall.

In prints such as Kahu (1977), his legacy extends into the 21st century. An elegant, minimal screen print in red and black, Kahu is located in the gallery space adjacent to Black Rainbow, a series of paintings by Ralph Hotere and Michael Parekowhai’s He Kōreropūrā kau mo te awanui o te motu: Story of a New Zealand River (2011). There is a shared sumptuousness and succinct regard for colour in Parekowhai’s work that alludes to Walters’ aesthetic, while Hotere’s paintings seem to acknowledge Walters’ empathetic engagement with an international arts practice enlivened through localised iconography.

In another section, Framing the View, nineteenth century landscape painting is rejuvenated. While its title may suggest a consideration of landscape traditions of the sublime, topographical or picturesque, Framing the View also references photography, furniture and design. Alfred Burton’s photograph, White Terrace from the Top (c.1885), is a view removed and distanced from the present day: a unique piece of the landscape that has vanished, preserved for posterity in black and white. Nearby, Frank Grady’s Table centrepiece, in the form of a Mamaku (tree fern) c. 1890, a small sterling silver sculpture, adds to a perception of the land as a strange and unfamiliar entity, a premise further complemented by a painting by the Messenger Sisters, Landscape with Settlers (1857). The other-worldliness of these works reveals a detachment from home and place for the Messenger Sisters construct a view of life in 19th century New Zealand that is distinctly disorientating. Alongside works like Nicholas Chevalier’s Cook Strait, New Zealand (c. 1884) romantic traditions of landscape painting begin to lose their optimism, and the certainty of ‘framing the land’ becomes highly questionable.

The section titled Emblems of Identity encompasses early modernist paintings from the 1930s and 1940s. The inclusion of portraits by M. T. Woollaston of Rodney Kennedy and Ursula Bethell act as a reminder of the small scale of art works during this period, evidence of a developing modern movement discovered and learnt from books and reproductions. These paintings also confirm the presence of this prominent landscape painter’s other life as expressionist portrait painter.

The highlight of Nga Toi - Art Te Papa is a series of five works by Colin McCahon, all painted in 1947: The Angel of the Annunciation, Entombment: After Titian, King of the Jews, Christ Taken from the Cross and Valley of the Dry Bones. Often included in survey exhibitions of McCahon’s work, they are generally placed within the context of larger and louder paintings like Victory Over Death 2. However, seen together, as they would have been when first exhibited, this grouping more than confirms how intuitively ‘right’ McCahon was as a maker of images. Christ Taken from the Cross is the work of a painter who perfectly understood the conventions of Renaissance composition and German expressionist painting, and reconfigured such traditions through the iconography of the New Zealand landscape. McCahon may have never painted anything better than this series. Appropriately, these works are introduced in the gallery through the placement of a sculpture by McCahon’s tutor in Dunedin, R. N. Field’s Madonna and Child, an image that resonates with the spirit of McCahon’s paintings from the late 1940s.

Being Modern brings a new consideration to local art from the post-war period. Its success again resides in its ability to look beyond painting to encompass furniture, design and craft, in this instance, from the 1950s and 60s. Design and fine art have never looked such good companions. Warm relationships are established between Ben Nicholson’s English Constructivist painting, Feb 2 1947 (Painting J.L.M), chairs designed by Garth Chester (c. 1955), Milan Mrkusich’s Buildings (1955) and Mirek Smisek’s Bohemia Ware Vase (1951-52).

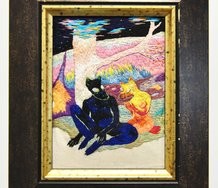

Home, Land & Sea takes in the period from the 1970s to 2000s. This is no doubt the most difficult section of Nga Toi - Arts Te Papa for ensuring that meaningful conversations between works take place. Variations in scale, materials, and philosophies about making and thinking about art in the later decades of the 20th century, typically give life to awkward contemporary curatorial hangs of public collections. Home, Land & Sea however, provides a generous allocation of space for a series of large-scale works that seem pleased to be occupying the gallery together. The application and dripping of paint in John Pule’s Shark, Angel, Bird, Ladder (2008) is shared by Max Gimblett’s Pearl of the Pacific 2 (2004) and echoed in the loose hanging threads of Don Driver’s Blue and Green Pacific (1978).

Gimblett’s work also seems fresh in the way it sits comfortably with other images linked to New Zealand’s relationship with the Pacific. In so doing it re-establishes a connection between his art and place of birth. In this and other instances throughout Nga Toi - Arts Te Papa the substance of good curatorial decisions is evident, revealing that the national museum’s agenda for the arts gives credence to the objects that they hold in their care, respectful of the potential of the ideas, ideologies, and materials and processes that inform them.

Warren Feeney

Recent Comments

Creon Upton

"Baudrillard is to NZ art what Alain Marfat is to NZ shipping." Nice.

Owen Pratt

Baudrillard is to NZ art what Alain Marfat is to NZ shipping.

Andrew Paul Wood

You would have to take that up with Baudrillard, not me

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 6 comments.

Comment

Owen Pratt, 9:38 p.m. 14 August, 2013 #

"the small scale of art works during this period, evidence of a developing modern movement discovered and learnt from books and reproductions."

If Rothko had painted his canvasses at one quarter the scale that he did; would this be the acceptable scale for modern art?

Perhaps the diminutive Kiwi scale is equivalent in isolated colonialism to the Amrican heroic luminism and its overblown gigantism, and a natural response to our environment, rather than some idea of a dim witted parochialism, reproduced images do come with dimensions after all.

Andrew Paul Wood, 1:23 p.m. 15 August, 2013 #

Nonsense - it comes from being divorced from familiarity with Rothko et al's scale due to distance. Hence a number of Canterbury painters of the 1990s were emulating surrealism on a larger scale without realising the orginals they were looking at were only the size of postcards.

Owen Pratt, 10:17 p.m. 16 August, 2013 #

Not so sure about that Andrew, its just an all too convenient piece of received wisdom and one that does artists no favours. Why stop at scale as a received idea; lets say the whole culture is a copy, just a distorted one with little or no understanding of where, when and how real art is made. A sad little reflection on the inside of a silver teaspoon.

Andrew Paul Wood, 12:42 p.m. 17 August, 2013 #

You would have to take that up with Baudrillard, not me

Owen Pratt, 1:59 p.m. 17 August, 2013 #

Baudrillard is to NZ art what Alain Marfat is to NZ shipping.

Creon Upton, 1:37 p.m. 18 August, 2013 #

"Baudrillard is to NZ art what Alain Marfat is to NZ shipping."

Nice.

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.