Mark Amery – 14 September, 2013

The Christchurch Art Gallery touring exhibition The Hanging Sky, represents the gamut of everything I like and take issue with large painting. Things start well. The big rock faces and skies, and magnetic abstracted representations of Mokomokãi or Toi moko, all with their air punctuated by tumbling bird ciphers, are powerful. The exhibition (and book) moves into a rich exploration of skywriting and the visual treatment of text. And yet here I start to find myself questioning the scale…

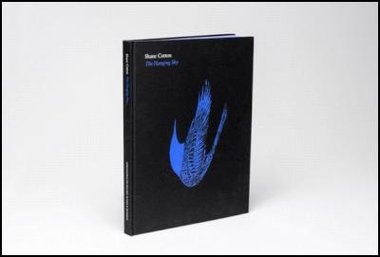

The Hanging Sky: Shane Cotton

Editor: Justin Paton

Essays by Justin Paton, Robert Leonard, Eliot Weinberger, Geraldine Kirrihi Barlow

Design: Aaron Beehre. Photography: John Collie

192 pp, hardback , foil-stamped cloth cover, blue page edges

72 full colour plates

Size 390 x 294 mm; weight 4.10 kg

ISBN 9781877375255

Published by Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna O Waiwhetu, 2013

A confession. I have been struggling with big painting of late. They fill big public gallery and corporate foyer walls nicely, but too few have a Rothko or McCahon sized visceral wallop to carry the visual bombast. Too few immerse me, charge me, change me.

Am I falling out of love with painting? Not exactly. Painting has to work harder to engage. Images come in a flood, increasingly digitised, ever more compressed and miniaturised. Painting, with a weight of historical baggage, is surrounded by a plethora of other media that relate in quite different ways to the world. And so on.

Of all the painters I can think of Shane Cotton is wrestling with this the most. I admire the boldness and rigour of his fluid investigation of painting, our contemporary conflation of different media, our cannibalisation of imagery, visual languages and pictorial techniques - and all the trouble it brings. Moving, in this new century, his viewpoint skyward he manipulates imagery in a charged, storm cloud-laden ether (the digital and spiritual space between things). His paintings express an anxiety over displacement, fragmentation and ungroundedness (the ‘dis’ and ‘un’ prefixes come up repeatedly in writing surrounding his work), both universal and culturally specific. The work is distinctly chilly.

And yet a wrestle it is. The Christchurch Art Gallery touring exhibition The Hanging Sky, takes in a selection of Cotton’s work from 2007 to 2013. It represents the gamut of everything I like and take issue with large painting. Things start well. The big rock faces and skies, and magnetic abstracted representations of Mokomokãi or Toi moko (tattooed Maori heads), all with their air punctuated by tumbling bird ciphers, are powerful. The exhibition (and book) moves into a rich exploration of skywriting and the visual treatment of text. And yet here I start to find myself questioning the scale. The elevation of uncertainty the work conveys at this large size bothers me. There’s an emptiness to the grandeur, as if taking on the vacuity of advertising at its own game. By the time I reach the suite of more recent work, with its library of cut and paste collage of co-opted, manipulated imagery, Cotton’s lost me in a self-referential design game. The work has lost its potency as paint, its rationale for being up large on canvas.

Which is where conversely the power of The Hanging Sky book kicks in. Many of the paintings work better in this mode and at this more intimate human scale. It’s a terrific piece of publishing. It would be a misnomer to call it a catalogue. It contains more work than the exhibition, allowing the viewer a better sense of the scope of Cotton’s experimentation with his vocabulary (particularly in the midpoint years of 2010-11). As something you flick rather than pace through, perhaps the book is the best mode of representation for what Paton calls a painting practise in motion. While an exhibition tends to define and contain, a book relies on a narrative of progression and change.

The book’s strength is arguably reflective of the fact that the Christchurch Art Gallery has been (as it has dubbed itself) “a gallery without walls”. It is lavish in its electric Persian Blue page edges and big scale, and yet it is not padded out. It exists to support the scale of the paintings.

A single page here is A3, a doublepage spread A2 - poster sizes. You hold it as a distinct object to immerse yourself in the work. Cotton has long worked with the design language of the street poster and graphic arts. His work then has a distinct charge at this scale. At this size the experience is also far different from what we are increasingly familiar with holding: the phone, pad and laptop screens. This book doesn’t fit in a handbag or briefcase. In this way it feels like a book made for this time, just as Cotton’s paintings in their visual language extend widescreen arrangements of icons, and the optical effects of the flickering liquid crystal display.

It’s not so long ago that an active printing practice was a common side activity for a painter. Cotton breaks down perceived boundary lines between the ends of the design spectrum. Particularly when, as he did with his last survey show in 2003 he created with Eyework design limited edition posters. Our notions of value with printing and the object are changing. Take the recent “most expensive album in New Zealand history”, the recently released Chills live album Somewhere Beautiful. Featuring a Cotton 50cm x 50cm screenprint it retails at $6500 (The Chills’ Martin Phillipps commenting to the Otago Daily Times that, “it’s probably an investment more for Shane’s art than the album at that price tag.”)

The Hanging Sky meanwhile is on sale at $120. With excellent photographic reproduction by John Collie and elegant design by Aaron Beehre it deserves to be a game-changer in terms of art book publishing. The sort of book you buy regardless of your art purchasing ability, because it offers you something your digital devices do not.

The process of painting remains integral to Cotton’s work, but comparing exhibition to book I question whether the painting is always the strongest experience. A series in 2008 in which images shot through with blue are stretched on a white page backdrop work far better in print than on the wall. A series of target works (acrylic, photo etching and aquatint, 2009-12) take a long wall to exhibit, but for all their delicacy and design strength they absorb my attention better as I flick through them on the page.

The language of design of course is not where Cotton’s works’ relationship with books ends. The works are veritable libraries of imagery and texts colliding, colluding and corroding. The works offer themselves up to be read, yet now also assert the deadliness of doing so. Readings constantly fade, warp or are crossed out. The work becomes more about the importance of the space in-between things, and the unreliability of reading that which punctuates it.

This gives their presentation in book form an extra charge - for the reader it’s an active engagement in the complexity of reading images. Robert Leonard’s title for his essay, ‘The treachery of images’ gets this beautifully. It itself is taken from a Cotton Hamish McKay exhibition, which is in turn stolen from Magritte -the title of his famous pipe painting (stating ‘Ceci n’est pas une pipe’). Such acts speak of the piratical mongrelisation culture involves, as so often vividly visualised as a form of violence in Cotton’s work.

Given Cotton’s rejection of being too easily read, its no surprise the writers in this book work to open his work out rather than close it. All are excellent. Leonard is good on Cotton’s positioning, or more the slipperiness of his positioning: his wish to engage with the space where positions move and meet and become problematic. His ruminations on ‘Maori as Vampiric’, based on hearing Cotton’s favourite film is Nosferatu, is an entertaining, vaguely useful segue-way in considering the tension between modernity and the older spiritual realm beyond.

Geraldine Kirrihi Barlow is of Irish, English and, like Cotton, Ngapuhi descent and a Senior Curator at Monash, Melbourne. In other words, she is well positioned to comment on both this works grounding and its floating hybridity. Its reflected in the strength of her writing: able to consider with some depth the presence of Toi moko in the work, and express the real world present charge of Cotton’s use of imagery through poetic phrase: “Disarticulated, these heads are like the smashed memory cards of defunct devices…” or “Cotton brings us fragments from history, from ‘incidents’ past, but casts them in the light of this ungrounded age, this economy of flickering, ever in motion, images.”

As guide, exhibition curator Justin Paton writes experientially of ‘six encounters’ with Cotton’s work, stretching over the time-span of the exhibition - the writing often brilliantly, breezily evoking what he says Cotton tries to do as a painter: “sound out and activate space”

Principal place upfront however is given to American essayist Eliot Weinberger, known for his conflation of prose and poetry. He reflects Cotton’s work as about space, movement of the past on the page and opening up interpretation. Weinberger makes the stories and spirit of our catalogue of native birds, present and extinct, alive as a performance, as a dance. It reads like the score of a choral work brought to life: ghost birds sing through the movement of words, colons and speechmarks. Like Cotton, Weinberger connects heaven and earth by charging up with play the unknown, dreamlike space in-between.

Mark Amery

Recent Comments

Ralph Paine

I get it Mark that we’re living in an age of cynical opportunism, but I doubt seriously that Cotton is ...

Mark Amery

Hi Owen, leading question! Of course not. I think he clearly likes to work to scale and is working to ...

Owen Pratt

Mark, are you suggesting that Cotton has purposefully made large bombastically, unsuccessful works, that come to life in the catalogue ...

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 7 comments.

Comment

John Hurrell, 10:06 a.m. 14 September, 2013 #

Thanks Mark, for your extremely useful review here.

It would be good to get some more discussion about this book. I feel - from my own close look at it - that Shane's images have moved away from painting and are now filmic. They're movie stills for some imaginary blockbuster. It would be great to have him team up some some hothot animator, and activate his subject matter with movement.

Ralph Paine, 9:48 a.m. 15 September, 2013 #

Painting, cinema, writing... Each preserves ‘images’ in its own way. Each is a different adventure. But are not all three already animated ("activated") by movement?

A very basic schema: painting is an immobile set of forces which we animate in our minds, walking in the gallery space; a book of writing is stillness incarnate until we animate its saying by following the sentences, turning the pages; but cinema is automatically in motion, introducing into our stillness a very direct animation.

Cotton chose painting as his adventure. There is no "drift" from this. In fact, I think he had absorbed the idea of the "filmic" right from the start. Upon setting out he had already transferred the thought of cinema into the realm of his painting studio, and thus into the specific problematic of that realm. And he had transferred the idea of writing too... To be painted: cinema, writing.

Locally—as with other painters of his and an earlier generation—McCahon is the great precursor.

John Hurrell, 11:01 a.m. 15 September, 2013 #

I think, Ralph, you are being more than a little precious about the 'own way' of painting - possibily provoked by my use of the dreaded word 'blockbuster'.

Some of the grey works in this book could be mistaken for photographs. And if Mark Braunias has successfully collaborated with an animator then - if so inclined (and he may not be) - it is a possibility Cotton might wish to explore. Heather Straka (another example) has successfully straddled both painting and photography, excelling in both - artists can choose to operate in several 'adventures' simultaneously.

Ralph Paine, 3:32 p.m. 15 September, 2013 #

Well yeah, artists can choose to conduct several adventures in one lifetime. And well yeah, they do. Perhaps with them, locally, Len Lye is the great precursor. Maybe.

Some artists lock up the studio never to return. No big deal.

And no big deal then that I think Cotton is a painter and that that's his adventure. Not even a big deal that I like setting up precious little schemas whereas you like speculating in puppy-dogish manner about what artists might do.

Someday, wow, it would be real cool bananas if....

Meanwhile, I look forward to getting The Hanging Sky: Shane Cotton outta the library.

Yeah, many thanks Shane: so far it's been WAY COOL (seriously!).

Owen Pratt, 6:25 p.m. 15 September, 2013 #

Mark, are you suggesting that Cotton has purposefully made large bombastically, unsuccessful works, that come to life in the catalogue so that he can maintain some kind of shamanistic shapeshifting aura?

Seems unlikely but I am intrigued as to the how and why the scale and medium can produce these wildly different (unintended and presumably unedited) effects.

John, between yourself and Mr Amery, can I look forward with eager anticipation to the first Shane Cotton Flick Book?

Mark Amery, 1:38 p.m. 26 September, 2013 #

Hi Owen, leading question! Of course not. I think he clearly likes to work to scale and is working to convey big things, but I am personally finding that not as convincing, and I also question how much of making big things is about tailoring to big gallery walls and the walls they might be purchased for (with big prices). As a viewer I find I'm not as affected always. While it works for some of the work, others the scale leaves me cold.

So its more scale, and sometimes media.

The idea of these works animated as John suggests is something I hadn't considered (Reuben Patterson an artist who's worked in this way) but as Ralph says is really Shane Cotton's prerogative - his most successful paintings already shimmer and move heaps without the need of flick books and animation - these are some of the best of the work from the last 10 years.

Ralph Paine, 4:23 p.m. 27 September, 2013 #

I get it Mark that we’re living in an age of cynical opportunism, but I doubt seriously that Cotton is much motivated by some square-yardage/$$$ ratio. From what I can figure he and his various gallerists have been managing to sell heaps of S M L XL Whatever-sized works ever since his début in the early nineties. In any case, I’d like to think (and you somewhat agree) that his motivation for painting ‘big paintings’ arose—and continues to arise—from a more hybridized ‘n’ historical zone: one encompassing the supply-store/studio/gallery/museum nexus, with all its attendant challenges, problems, experiments, potentials, etc; but also the different genealogies involved. Sure, money is an important practical aspect, but put simply: (some) painters like to try their hand at large scale work because it’s part of the adventure.

But if in your view Cotton has had his successes and failures in the ‘big painting’ department, you want to link his recent ‘failures’ to a gnawing disenchantment within yourself toward contemporary ‘big painting' in-general. In other words, it’s become for you a Zeitgeist thing, one in which the miniaturisation of the image ecology has lessened the impact of the XL...

Art tourism beware!

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.