Megan Dunn – 18 November, 2013

Good art is hard to sell but McLeavey has faith. Faith is a recurring theme. McLeavey values art as more than a commodity. Art is presented as a spiritual quest. McLeavey's belief is infectious; his ability to pass on this reverence is the secret of his success. It's clear he often doubted his practice, wondering if he should up-size the gallery and move the business to Auckland or overseas. In the end his commitment to Cuba Street has paid off.

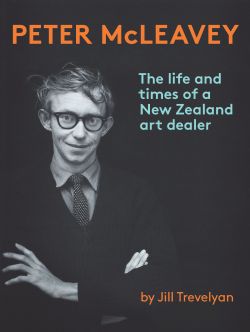

Peter Mcleavey: The Life and Times of a New Zealand Art Dealer

Jill Trevelyan

Hardcover, 496 pp, over 200 b/w and colour illustrations

RRP $64.99

The Matterhorn was gridlocked at the launch of Jill Trevelyan’s new biography Peter McLeavey: The Life and Times of A New Zealand Art Dealer. A harassed bouncer policed the Cuba Street entrance refusing to let art goers in without an invitation: thou shalt not pass. Complaints. Consternation. The crowd of well wishers gathered outside the Matterhorn all felt they had some small stake in Peter McLeavey’s biography and did not need an invitation to prove it. Family members soon emerged at the entrance to smooth any ruffled feathers and let the ‘uninvited’ VIP’s proceed at pace. I’d been forewarned that the physical invite was more than cursory and came prepared. The Peter McLeavey book launch was the Wellington art event to be at.

As McLeavey notes in the introduction, “all good galleries are essentially autobiographical.” Exactly. Published by Te Papa Press, Trevelyan’s biography is the first on McLeavey and covers the forty-five year history of the gallery including the careers of many definitive New Zealand artists: Colin McCahon, Gordon Walters, Toss Woollaston. McLeavey is such an attractive subject because his story is intertwined with the evolution of New Zealand art. The launch of his biography was an opportunity to acknowledge a life’s work, to take our hats off to the man in the hat. But I’m sure many people in the audience also hoped to catch a glimpse of their own lives in the book’s hallowed pages - or at least read a footnote about a friend of a friend.

Rumour has it over 600 people were at the Matterhorn. It felt like it. I could barely make it beyond the bar. Not a bad place to be as the speeches began.

Olivia McLeavey read out the speech Peter had written for the occasion, including this quote from a Denis Glover poem; “I do not dream of Sussex Downs/Or quaint old England’s quaint old towns/ I think of what may yet be seen/ In Johnsonville or Geraldine.” Humourous and humble, Glover’s poem has remained a source of inspiration to McLeavey, validating his decision to take his stand here. McLeavey’s speech evoked an earlier cultural landscape, the land of the long white cloud back before Colin McCahon was our big ‘I Am.’

He went on to acknowledge author Jill Trevelyan and thanked the artists and his family, including his partner, Hilary McLeavey. I was equally touched that he acknowledged early art dealers like Helen Hitchings and Barry Lett. At the end of his speech, Olivia McLeavey told the crowd Peter was, “a bit of a shutterbug” and drew our attention to the photographs that lined the walls of the Matterhorn. Peter’s photographs showed off the many sultry, ramshackle guises of Cuba Street.

John Reynolds spoke last. He talked about a mid-afternoon meeting he’d once had with Peter at Smith and Caughey’s cafe. McLeavey had warned Reynolds before this meeting that he had something to tell him. Reynolds was rife with anxiety: what did a mid afternoon meeting mean? He knew he was not the first artist on Peter’s list of Aucklanders to visit but he wasn’t the last. Reynolds entertaining speech captured some of the formality and ritual Peter McLeavey is known for; he compared the art dealer’s manner to a Vatican emissary. Reynolds’ anecdote also highlighted one of McLeavey’s central qualities: mystery. The audience at the Matterhorn waited to hear what it was McLeavey had to say that afternoon in Smith and Caughey’s cafe. Finally the punch line was revealed. Peter McLeavey shared this quotation with John Reynolds, “live secretly.”

How secretly?

In the context of a biography launch Reynolds’ anecdote was well timed. On page 398 of the book is an invite to McLeavey’s seventieth birthday party: a Photo-shopped image of Peter McLeavey next to Sharon Stone on the cover of a Woman’s Day magazine. The headline reads ‘Peter and Sharon tell all’. So, do Peter and Jill tell all in this biography?

Trevelyan begins with the lives of McLeavey’s parents, railway worker, Leslie McLeavey and his fashionable wife, Betty Tiernan. The early chapters depict McLeavey as a young intellectual - a serious reader - growing up in a provincial society. My favourite insight into McLeavey’s character occurs at the end of Chapter Two. Returning to New Zealand onboard the SS Southern Cross, McLeavey abandons the semi-autobiographical novel he has been writing by throwing it into the sea. Touché. I admire that young writer’s steel. The decision to discard the book is an act of taste. And taste is an art dealer’s stock and trade.

Trevelyan’s primary focus is the birth of the gallery and the growth of modern art in New Zealand. Containing a complete list of exhibitions from 1968 to 2013 and 42 pages of notes, this biography is immaculately researched; a historical resource that will be cited by students and curators for years to come. McLeavey is renowned for his analogue approach and Trevelyan has had full access to the gallery archives, including correspondence, exhibition files, and diaries. Her research is blended unobtrusively into McLeavey’s story. The biography reads chronologically but is a deft weave of artists and key events.

Viewers familiar with Luit Bieringa’s 2009 documentary The Man in the Hat will recognize overlapping information. The book shares some of the same quotations and photographs. That’s not a necessarily a weakness however.

McLeavey held his first exhibition in his bedroom on the Terrace in 1966, then moved to his current Cuba Street premises in 1968, often working 60-hour weeks to cultivate a stable of artists and collectors, “selling dreams.” “It was a Clark Kent sort of Life,” Mcleavey says, referring to his early days working part time at Graur’s Electrical and Battery Services. At midday he finished his shift, changed into a suit and tie and went to work as an art dealer. The gallery did not make a profit for the first three years. Trevelyan highlights the fiscal realities of running a small business. In darker moments throughout the biography

McLeavey relates to Willy Loman from Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman.

Peter McLeavey emerges in these pages as a man of letters. His correspondences with artists are esoteric and personality driven, tender and terrific. The letters still seem fresh even though it’s hard to imagine a younger generation of artists making some of the passionate statements committed to paper. E.g. McCahon writes to McLeavey; “Painting must operate on a most basic level…like pigs fucking. That’s what it’s all about.” I’m not sure I follow McCahon’s simile. Maybe I don’t know enough about pigs? Or maybe I don’t know enough about painting? Either way I like the oink on offer. McLeavey describes Catholicism as the skein of his relationship with McCahon. “I was a believer. Colin liked that.”

Good art is hard to sell but McLeavey has faith. Faith is a recurring theme. McLeavey values art as more than a commodity. Art is presented as a spiritual quest. McLeavey’s belief is infectious; his ability to pass on this reverence is the secret of his success. It’s clear he often doubted his practice, wondering if he should up-size the gallery and move the business to Auckland or overseas. In the end his commitment to Cuba Street has paid off. How McLeavey knew which artists to show remains slightly elusive. Trevelyan doesn’t dwell on issues of artistic merit because she doesn’t need to. Nor does her biography drill down into the ratios of artists in the McLeavey stable from Auckland vs. other areas of the country.

The professional relationships McLeavey ended are revealing. Don’t mess with the chaise longue. Merlyn Tweedie still holds the record for the shortest show at the gallery. Richard Killeen describes her unauthorized paint job on the chaise longue as one of those “mafia type, horse-head-in-the-bed sort of situations you never forget.”

McLeavey’s letter to Billy Apple is another brilliant example of the dealer as author.

“I note your request for me to amplify my decision to discontinue handling your work. All I can add to my earlier letter is that I’m tired. Tired.”

I love that final full stop like a small exhausted sigh; a one word sentence of weary brevity.

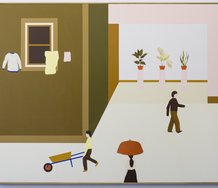

McLeavey’s longevity is owed in part to his ability to divine the talent of successive generations, exhibiting artists as diverse as Richard Killeen, Julian Dashper and Yvonne Todd. The late Don Binney speculates, “he was living through different sub-epochs of cultural change. In a way each one was incompatible sequentially with the last, and it was either him or his artists who had to go.” Binney’s comment sheds light on how McLeavey has managed to stay in business for over forty years. The artists that book end the gallery’s history have different thematic concerns, the representation of New Zealand and its landscape are not centre stage anymore.

In June 2010 Peter McLeavey wrote to tell friends and associates he had Parkinson’s disease. Olivia McLeavey has since taken over the day-to-day management. The history of the gallery is a national inheritance. The running of the gallery is a family business. In the past couple of years artists have left the stable, Andrew McLeod and Liz Maw. Others have joined, Ben Cauchi, Octavia Cook. Trevelyan’s epilogue does not go into details about the politics of these recent developments. Instead the biography ends on a letter from Peter to Auckland painter, Andrew Barber. “How do you protect your gift; how do you keep it from becoming formulaic. The answer lies in the future.”

Peter McLeavey: The Life and Times of a New Zealand Art Dealer is a portrait of vision. McLeavey remains enigmatic, his character left intact despite the inclusion of candid information. And every biography has its omissions. Trevelyan’s book is defined by her subject’s composure; grace.

In this desecrated age of open information we still need to live secretly.

Megan Dunn

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.