Warren Feeney – 29 December, 2013

Johnston's narrative is about an artist who happens to be living in the Pacific, and is heir to European traditions of printmaking; Albrecht Durer, Honoré Daumier, Francisco De Goya, J. J. Grandville, George Stubbs and Paul Klee. Cleavin comprehends the potential of the print as a political tool, and satire as an assured means to consider the gap between appearance and reality.

Melinda Johnston with T. L. Rodney Wilson.

Lateral Inversions. The Prints of Barry Cleavin.

Hardback, 288 pp

RRP $55

Christchurch: Canterbury University Press, 2013.

Recounting more than five decades of etchings and drawings by Barry Cleavin, Lateral Inversions. The Prints of Barry Cleavin is distinct from the majority of recent books surveying the work of New Zealand artists. Unlike, for example, Ron Sang publication, Pat Hanly, (2012) or the Christchurch Art Gallery’s Shane Cotton the Hanging Sky (2013), Lateral Inversions is not a book that overtly announces the grandness of its intentions.

Far more modest in its physical dimensions, it also seems to intuitively offer commentary on where printmaking is currently situated in the hierarchy of the visual arts in this country. A potentially less rowdy presence on the coffee table and also a more intimate reading experience, it nevertheless retains a thoroughness of enquiry around Cleavin‘s practice in a text by Melinda Johnston that encompasses 120 prints and drawings (1996 - 2012), complemented by astute, personal memories of the artist by Cleavin’s recently-deceased, longstanding friend, T. L. Rodney Wilson.

Lateral Inversions is the story of a master printmaker, an influential educator and arts advocate. Senior lecturer in printmaking at the University of Canterbury from 1978 to 1990, and Officer of the New Zealand Order of Merit (ONZM) in 2000 for services to the arts, Cleavin also emerges as an artist whose practice remains separated from many of the issues and ideologies central to New Zealand art over the past five decades. Cleavin’s oeuvre has tended to be indifferent to ‘distance looking our way,’ national identity and perceptions about the country’s cultural status internationally.

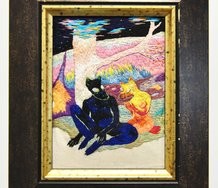

Cleavin’s Sacred Cow No 4 (After Sutton), 1974, confirms that his attention had generally been focused elsewhere. William Sutton’s iconic Nor’ Wester in the Cemetery is literally confined and impounded. Cleavin comments: ‘We… only have only got so much history to actually build our heroes in.’ Instead, Johnston’s narrative is about an artist who happens to be living in the Pacific, and is heir to European traditions of printmaking; Albrecht Durer, Honoré Daumier, Francisco De Goya, J. J. Grandville, George Stubbs and Paul Klee. Cleavin comprehends the potential of the print as a political tool, and satire as an assured means to consider the gap between appearance and reality.

T. W. Rodney Wilson’s recollection of his time with Cleavin as students at the University of Canterbury School of Fine Arts in the early 1960s, may offer some clues as to why Cleavin felt it unnecessary to aspire to belong to a local tradition of art making. Wilson details the limited resources of the School of Fine Arts and its lingering allegiance to the English Kensington System of art education. Equally telling are his disclosures about an arts community characterised by its innocence and ignorance - Christchurch’s public gallery, the Robert McDougall Art Gallery, hanging paintings by John Piper and Ivon Hitchens upside down, and students from the School of Fine Arts, attempting to construct a localised modernism at the Canterbury Society of Arts gallery in ‘self-consciously avant-garde 20/20 Vision shows.’ Cleavin’s formative practice is incisively described by Wilson as a ‘hybrid art school, grafting an emerging interest in contemporaneity and internationalism onto a regionalist academic tradition.’

Cleavin’s graduation from the School of Fine Arts in 1966 however, did coincided in a brief and beneficial interest in New Zealand in printmaking, according it a respect that had never been bestowed upon it previously or would be again. The exhibition New Zealand Graphics 1966 at New Vision Gallery in Auckland and the establishment of the New Zealand Print Council, (of which Cleavin was a foundation member), signalled that printmaking, at least in the mid-1960s, was of significant to an emerging contemporary art. The expressive formalism of artists like Hanly and Ralph Hotere appeared like a regeneration of traditions previously consigned to the 19th century. Yet, even a cursory glance at Cleavin’s prints reveal that his practice was as removed as it was connected to the spirit and direction of printmaking at this time. Meticulous and skilful in the execution of his prints and his ability to record the detail of his subjects, Cleavin’s etchings demonstrate little interest in the gestures of expressionism or abstraction.

If Lateral Inversions has a subtext it is about the ways in which Cleavin’s practice pays so little attention to the agenda of the country’s art commentators, curators and galleries. Johnston argues that satire - as a means to consider and open up a complexity of ideas, conundrums and truths - is fundamental to the experience of his art. And if his work has, in the best traditions of printmaking, given due attention to the meticulous and skilful execution of its subjects, Cleavin has accorded satire equal consideration - a means of expression in the visual arts, equally uncommon in New Zealand art. (How many other artists have understood the value of satire? Tony Fomison and Jacqueline Fahey? - the list is a short one.)

However, most criticism levelled at Cleavin has been focused on his ‘detachment’ from the subjects his narratives dissect. In the early 1980s, a series of erotic prints were panned by Cheryll Sotheran, because ‘the sexual bias the works display severely limits their value as serious social commentary.’ (On this occasion, Cleavin’s prints were an easy target. The emergence of feminist arts practice during this period ensured that Cleavin’s ‘objectification’ of his subjects was a perfect culprit for deconstruction.) Wider public controversy surrounded the inclusion of such images in Cleavin’s touring exhibition, Ewe and Eye (1982 - 1984). A Nelson City Councillor described one print as a ‘grotesque, distorted attempt to display the human form,’ and requested that the Council’s annual grant to the Suter Art Gallery be deferred. Johnston addresses such criticisms, arguing that the ‘explicit’ content of Cleavin’s prints recognise the complexity of all realities and consider human behaviour as something far more than a ‘simple black and white framework’ - any perceptions about Cleavin’s objectification of his subjects, is merely evidence of the quality of their execution and prevents his art from descending into sermonising.

Essential to Lateral Inversions is Johnston’s assertion that Cleavin’s work belongs to a history of European printmaking, and that the artist wholly comprehends and embraces its conventions and customs: Satire and irony, the exposition of the gap between appearance and reality, or the evident paradox that frequently exists between the print’s title and its narrative. Johnston identifies a commonalities of themes, reoccurring motifs and imagery. Irony frequently occupies centre-stage. For example; the smiling mask-face the artist wears in Self Portrait - a face to get him through the trials of life; animals assuming the habits and behaviours of people, complicating our grasp of the nature of human behaviour, (The Tribute, 1974, or, And They’re Off, 2004); and titles that serve to further obscure our reading of the image. (M. Duchamp Ascending HIS Staircase on a Bicycle, 1986, or, Moeraki - A Place to Rest by Day. 1991).

Yet, curiously, Cleavin’s prints are at their best when the ingenuity of titles and the enigma of his narratives, surrender themselves to the authority of the image. For example; the ambiguity of spatial relationships in Jeanette Looking, 1978, and the way in which this locates the figure nowhere and everywhere - Life-drawing model suspended in time, or individual adrift and dislocated, anxious or fulfilled in a particular moment?

And on occasions, a pun like, A Host of Allegations - Some not fully Substantiated, can overstay its welcome. Yet, this print remains a perplexing image. The repetition of the skeletal alligator as metaphor for an edition series of prints and its design and cumulative beauty, partake in a narrative that humorously touches on the brevity of existence.

Johnston and Wilson also comment on the supreme authority of Cleavin’s imagery within his practice: Wilson notes:

Cleavin’s images are enigmatic and elusive… [yet] they are so full of references to images, ideas, words, books, manuals and other things outside them that they often entice the viewer into an attempt to unravel their meaning. To approach them in this way is, in my mind wrong.

Johnston reaches similar conclusions, observing that objectivity alone, may only lead the viewer into corners. She notes that in Cleavin’s world ‘nothing is as it seems’.

If there is a place that Cleavin occupies in New Zealand art, it is his position as part of a generation of post-war artists who advocated for a broader consideration of what New Zealand might be. Although beginning this review by contrasting Lateral Inversions with Ron Sang’s publication, Pat Hanly, the work of both artists shares much in common: Art as a means to consider the political; to scrutinise male and female relationships; European traditions of art making as a kind of anchor to their practice, and their understanding of art as all-embracing in its ideologies - the personal, political, national and international. A shared and genuine faith in art’s ability to make a difference.

Warren Feeney

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.