Daniel Webby – 1 May, 2014

Clearly history is an important factor in becoming situated, but there is a balance to be struck between looking backward and imagining forward. This same distinction could be thought of in terms of describing and interpreting, or loath to say, theorising. As a journal Reading Room 6 would have been much richer for the inclusion of contemporary attempts to come to terms with the important question which resides at its core.

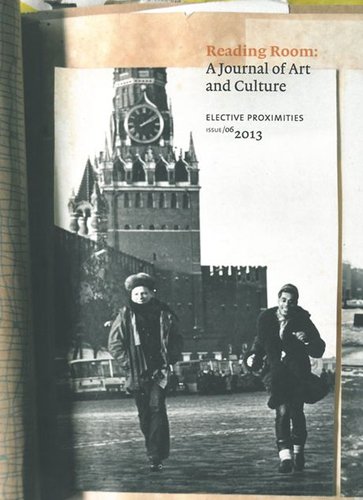

Elective Proximities

Edited by Christina Barton, Natasha Conland and Wystan Curnow

Managing Editor: Catherine Hammond

Published by Auckland Art Gallery, 2013

There’s an inevitable flattening which accompanies the term globalism. Not to invoke the spectre of homogeneity which accompany various accounts of globalisation, simply an acknowledgement of the losses which occur when systems theory attempts global scalability. Knotty n-dimensional particulars are shredded, pulped and laid out to dry as a surface not so much smooth as uniformly lumpy. And across this surface are ascribed markets, networks, ecologies or any number of competing conceptual maps which implore us to consider the flows, accumulations, emergences and disappearances across the system as whole. Culturally, politically and economically the specific and concrete make way for the general and abstract in a form of mapping which seeks not only to represent our individual experiences within a wide range of discontinuous and divergent realities, but also to set the terms for our navigation within such.

And it is this question of navigation which I find crucial in the discourse of globalism. There is no denying interconnection and circulation as defining features of contemporary experience, but how to make use of the vast conceptual constellations which are charted, attenuated as they are by equally vast aggregated data-sets, in order to plot a course, or perhaps of primary import, to come to terms with where we might be situated. With this in mind, I was excited by the prospect of the Elective Proximities issue of Reading Room, from Auckland Art Gallery’s E H McCormick Research Library, as “a situated response to the imperial claims of globalism”.

Etymologically “situated” extends from “site”, inferring a specific location, but situated can also be thought of in terms of the negotiation of place across both site and sign (or map). In this later sense, becoming situated is a process of orientation and of establishing bearings rather than seeking a fixed determination of place. Wystan Curnow further expands on the theme in the introduction to Elective Proximities, describing the editors’ desire for:

“…a geopolitics of situatedness and connection whose terms are more fluid and less predictable than those laid down by oppositions like centre and margin, local and global, isolation and assimilation”.

And this short paragraph starts to describe the tensions at play both within the current geopolitical landscape and, I suggest, the political imaginaries called upon to orient us toward its reshaping. With intrinsic and stable meanings deconstructed, fluid terms are called on as a form of political resistance, a rewriting of the power relations embedded in language. However, J G A Pocock expresses a wariness for such processes in the first essay of Elective Proximities, ‘Deconstructing Europe’, which explores the terrain emerging from such semantic destabilisation whereby:

“…all history is invention, and that invention is alien and an imposition; any context in which the self might find meaning is imposed on the self by some other, with the consequence that the self is always false, an imposition or imposture against its own unrealisable existence.”

In a gesture which mirrors the essay’s theme of relocated (dislocated) cultural heritage, Pocock summons the owl of Minerva, an ancient Greek symbol of wisdom and erudition, to carry the reader through a travelogue of empire, drawing out questions of identity across historic and contemporary European territories, arriving at a lament that:

“…we may be looking into a world where the post-modern which is indifferent to history lies side by side with the pre-modern which cannot rule history and is ruled by it”.

The scope of the essay is broad, to my mind too broad - “this essay is designed to ask questions about the voice of politics and history in the conversation of mankind” - but coherent and offers a very clear position. Writing as the neoliberal economic revolution was well underway, Pocock meditates on his contemporary situation (1991) as ushering in a post-political, post-industrial, post-modern ideology in which:

“…affluent populations wander as tourists - which is to say consumers of images - from one former historical culture to another, delightfully free from the need to commit themselves to any, and free to criticise while determining for themselves the extent of their responsibility.”

Pocock’s critique is focused on “post-modernist intelligentsias” but it is his rich understanding of European history, with accompanying historiographical readings of such, that constitutes the substance of the essay. In a sense the repeated polemical jolts which return the reader to an awareness of the problem that is the writing of history; the potential for political agency in constructing an account of history; and the erosion of this agency as a feature of post-political market communities gets in the way of what is an effective counter to these same arguments; namely, that critical accounts of history are indeed possible.

In contrast to the weight and density of the problems Pocock describes, his responses to such are glib and offer a fragile foothold in the unstable landscape outlined, seemingly unable to leave behind the logic under attack; as critique of post-modern thought, Pocock’s essay is thoroughly post-modern in approach.

Perhaps Frederic Jameson provides an interesting footnote here - from The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism (1984), Jameson outlines the task which Pocock’s critique necessitates:

“This is not then, clearly, a call for a return to some older kind of machinery, some older and more transparent national space, or some more traditional and reassuring perspectival or mimetic enclave: the new political art (if it is possible at all) will have to hold to the truth of Postmodernism, that is to say, to its fundamental object - the world space of multinational capital - at the same time at which it achieves a breakthrough to some as yet unimaginable new mode of representing this last, in which we may again begin to grasp our positioning as individual and collective subjects and regain a capacity to act and struggle which is at present neutralized by our spatial as well as our social confusion. The political form of Postmodernism, if there ever is any, will have as its vocation the invention and projection of a global cognitive mapping, on a social as well as a spatial scale.”

In contrast to Pocock’s pressing arguments for the production of history, Anna Parlane’s ‘Goes Most Anywhere: The Vehicle as Motif in the Art of Michael Stevenson’ provides a welcomed rhetorical distance with which to view the processes of history as rambling and aleatory.

Following Stevenson from his time as a student in Auckland, his early painting practice in Palmerston North to an exploration of the trans-national projects he is now well known for, Parlane’s writing is wonderfully poised and thoroughly researched, carrying the reader effortlessly through the work under consideration.

Broken into four periods, Parlane’s structure plots a movement toward the more fluid terms outlined in Curnow’s introduction. ‘Mongrel regionalism’ discusses Stevenson’s exploration of itinerant cultural forms such as the Ford Falcon in his painting practice of the late 1980’s. ‘The Balance of Payments’ looks at the economic and political forces which were the material of Stevenson’s 2003 Venice Biennale project, ‘This is the Trekka. The Price of Autonomy’ focusses on Stevenson’s Argonauts of the Timor Sea, Parlane drawing parallels with the precarious journey from Darwin to Indonesia taken in 1952 by Ian Fairweather aboard a bricolaged raft to Stevenson’s own precarious position as cultural producer navigating a “global network based on relentless movement and transaction”.

The final period is titled ‘Theory of Flight’ and opens with a description of Jose de Jesus Martinez; a Nicaraguan born Panamanian mathematician, philosopher, solider, poet, playwright, pilot and body guard who constitutes the central narrative thread in Stevenson’s A Life of Crudity, Vulgarity and Blindness (2012) presented at Portikus gallery in Frankfurt. And while the biographical information provided by Parlane adds a textual richness, it is her simple description of the exhibition which most deftly demonstrates Stevenson’s ability to build outward from appropriated narratives to construct material propositions not fully reducible to language. In material terms the show consisted of a near life-size replica of Martinez’ single-engine aircraft, installed in a glass roofed attic - visible from outside but not accessible. A shaft added to the exterior of the gallery carried light from the attic space down two floors to a darkened exhibition space where the light was reconstituted in the form of a camera obscura projection onto the gallery wall.

In my mind, interpretation of the work is all but unnecessary and Parlane refrains from doing so, offering a few simple pairings with which to consider it. The image and its object. History and its agents. Autonomy and its cost. To return to the situated response proposition of Elective Proximities, this work, and Parlane’s writing, makes material one of the most difficult to apprehend trade-offs in the movement toward fluidity, namely that “exquisite mobility is ephemeral” and to which I would add, impossible to touch and to hold.

In contrast to the conceptual maps offered by Pocock and Parlane, Phil Dadson’s contribution to Elective Proximities provides a more subjective view of interconnectedness. A delicate and unassuming suite of writing, collectively titled ‘Sound Stories’, Dadson’s intimate renderings of encounters, situations, and exchanges experienced in numerous locations around the globe are rich with the textures of people and place. While sound forms the basic currency of the writing, this currency circulates in many forms through performance and celebration, suburban and remote settings, pornography and bird sanctuaries, and featured on several occasions is the latent geological voice of song stones.

I would highlight one story in particular, titled ‘TSCHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHH,’ in which Dadson recounts a literal “culture jamming” exercise carried out while travelling through Chile. Under the guidance of a local host, the sound indicated by the title was projected in voice by Dadson and driver at an in-car device, the sound preventing electronic road-user tolls from being collected. While my rendering is reductive, the action as described by Dadson has a compelling resonance - a low-fi response to control technologies.

Following Dadson’s personal reflections on the experience of place through sound, the journal includes a round table discussion between Lee Weng Choy, Michelle Antoinette, Jon Bywater, Joselina Cruz, Sophie McIntyre, Viviana Meja, Joyce Toh and Nina Tonga, titled, ‘Where I’m calling From: A Roundtable on Location and Region.’

Lee Weng Choy, a curator based in Singapore, starts the conversation by asking the group to locate themselves. Stating a particular interest in intersected nodes over points, Choy implores participants to describe in real and imagined terms their current location, tracing the “trajectories and detours” via which this location was arrived at. The responses are varied, but tend toward a reading of geographic trajectories as career path.

The conversation livens up after introductions are out of the way, exploring themes of regionalism (What is it? Who decides the terms of definition? How should it be situated in relation to dominant narratives?), ethno-geography (Is this the form of knowledge being produced in international biennale? What views are being privileged and why?) and the practice of curating with these prior considerations in mind.

Choy’s own account of cultural consumption in the global art market makes for disheartening reading:

“Curators, critics and artists often speak about global society’s increasing appetite for consuming cultural difference. Part of this desire for the other is the desire to make it instantly available, to erase the separations between distinct places and cultures. The impulse to map is over-determined by many desires but one of them - to command a privileged view from above - is precisely about having the power to see it all and render distance abstract.”

For me the most vivid accounts of place are brought to light as considerations of contested spaces, discussed in concrete terms. As Jon Bywater comments, “Location is not something to be settled and put aside, but an action more than a fact”.

One such response comes from Nina Tonga, a doctoral student and teaching fellow at the University of Auckland who discusses Yuk King Tan’s Island Portrait which explores “dollar diplomacy” in the Cook Islands - the provision of resources, in this case Chinese civil engineers, as a means of gaining influence in the region. Such real world implications of the themes under discussion appear infrequently in the conversation - there is mention of the “refugee issue” in Australia, a nod to colonisation, and a discussion of naming conventions but each seem rhetorically positioned and resist asserting a position. In a sense Pocock’s arguments become quite telling and as Choy describes, distance, as in the space between people, places and cultures, seems rather abstract.

Christina Barton’s ‘Together/Apart: Regional Networks in a Global Age: Imagining the Pacific in 1976’ provides a view of two early attempts to position New Zealand as a cultural hub in the Pacific region, the South Pacific Festival of the Arts and the First Pan Pacific Biennale.

Peter Brunt’s contribution ‘Nicolai Michoutouchkine and Alio Pilioko: The Perpetual Travellers’ provides us with a view of this nomadic pair as they collect artifacts from around the Pacific toward the establishment of Esnaar, an “anti-museum” and home in Port Vila, Vanuatu.

‘The Weight of The Light From Above Brought to Bear On the Froth of the Waves on the Sea’ by Andre Vida offers a snapshot of collaboration across sound, poetry and motion, with Lawrence Weiner’s text sculpture awkwardly recast as title.

‘Mildura Sculpture Triennials, Australia’ by Jim Allen and Eric Riddler’s ‘Sculpture in Sunraysia: New Zealand Artists at the Mildura Sculpture Triennial’ provide two views of this now extinct triennial phenomenon, while Charlotte Huddleston’s ‘A Little Knowledge Let Loose on an Untrained Mind: Jim Allen as Educator’ is a very focussed essay on the influential teacher and artist.

To return to the proposition of this issue of Reading Room, that is as “a situated response to the imperial claims of globalism” and with the consideration of navigation in mind, the retrospective focus of a majority of the writing is disappointing. Clearly history is an important factor in becoming situated, but there is a balance to be struck between looking backward and imagining forward. This same distinction could be thought of in terms of describing and interpreting, or loath to say, theorising. As a journal Reading Room 6 would have been much richer for the inclusion of contemporary attempts to come to terms with the important question which resides at its core.

That said, having moved back and forth through this text on several occasions, it is the image of a small plane, tucked into an attic and reflected onto a wall several floors below that I cannot shake. With the attendant question of whether to orientate toward the image or the object (alongside the other pairings Parlane has offered) the work presents a certain figure of doubt, but it is a doubt made concrete, and as such, in a path toward becoming situated, perhaps a good start to place.

Daniel Webby

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 1 comment.

Comment

Owen Pratt, 9:31 a.m. 3 May, 2014 #

Small plane Cessna or small plane tessera?

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.