Mark Amery – 30 September, 2014

There’s a constant movement, a tornado of energy that sees all ungrounded and swirling like Dorothy’s house in Kansas. As the images tumble and anecdotes roll, sliding across each other, we watch Kentridge himself (in an odd nod to silent comedy) clambering over parlour chairs, as if trying to break time by going backwards. Relishing a human awkwardness, it’s as if he’s constantly, frantically, tripping over time as a piece of human furniture.

Wellington

William Kentridge

The Refusal of Time

5 September - 16 November 2014

There’s a fair amount of hoopla and plenty of marketing spend around the arrival of this installation, on loan from the Art Gallery of Western Australia, originally commissioned for Documenta 13 in Kassel, 2012. It feels like a return to the Paula Savage years at City Gallery: pulling off coups with blockbusters by significant artists not seen enough here, building on strong Australasian relations.

These have often served the gallery’s attendance figures and popular profile well, particularly when the work has the large room-filling wonderment factor of a Yayoi Kusama, Patricia Piccinini or William Kentridge. The video vitrines under the portico entrance have even returned to their old function - displays for TV advertisements for the show inside, rather than a curated programme of moving image.

This is observation rather than criticism. Without this basic outreach work New Zealand can feel awfully globally provincial in terms of the circulation of significant work. I just wish some of this relationship-building boldness could be applied to national curation.

Kentridge is arguably South Africa’s most well-known artist internationally. He is renowned for the way, through drawings and animations employing stop motion techniques - digitally revitalising the handmade - his work holds a transformative flickering magic and emotional truth in storytelling. I’m no globetrotter but I’ve managed to see and be spellbound by Kentridge at the Sydney Biennale, Auckland Art Gallery and, recently, in an exhibition of South African artists in San Francisco.

Mixing sculpture, spatial soundscape and a 30 minute five channel video work incorporating drawing, theatre, music and dance, The Refusal of Time is billed by the gallery as “his most spectacular to date”. It was also recently acquired jointly by New York’s Metropolitan Museum and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.

All this led to expectations that proved too high.

You enter a large darkened room. Wooden battened, it’s an old warehouse with chairs for you to sit on scattered almost violently at odd angles. No uniformity here, there’s an edge of Orwellian menace as well as melancholy. Film flickers across the walls interacting with collage patches of colour. I think of the artist et al.

A tension with order is suggested. Like some 19th century early industrial factory relic, near the centre of the room a large wooden loom-like mechanism, all well-oiled and carpentered pistons and axles, quietly swooshes wooden cage lungs backwards and forwards. The sculpture appears inspired by Kentridge’s interest in a system that attempted to regulate clocks in Paris in the 19th century, through a central mother clock bellowing air down tubes below the city (recounted as one aural fragment of many).

Akin to an early kinetic figurative modernist sculpture, the ‘elephant’ or ‘breathing machine’ as Kentridge calls it, suggests (though not satisfactorily for me convey) the idea of breathing for the whole room. It is trying to keep time at the centre of an audio-visual swirl of fragments and disembodied movements, an expression of the human fallibility of time, and the machine’s ultimate reliance on strong human relationships and communication.

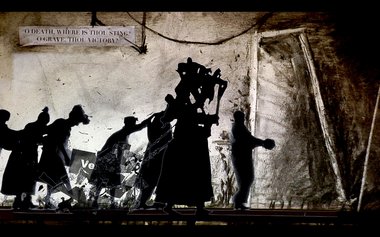

The film has a musical rather than dramatic structure, but remains fragmented. With a conceptual ambivalence to any one way of structuring space and time it resists resolutions of all kinds. It begins with a set of metronomes that fail to stay in sync, and ends with a march of silhouetted figures (cleverly merging collaged constructions and filmed performers), carrying old colonial mechanisms, trying to hold a collective musical rhythm, with the breathing pump of brass music. What might initially seem joyous, ultimately feels like a chained procession behind a coffin heading towards a black hole at the end of time. Even then this neat ending is structurally undone by the inserting of a quick dramatic scene after it.

Between these bookends is a surrealist medley of different approaches to filmmaking, the fast snippety pace recalling Kentridge’s work with scissors and paper. It’s a parade of early cinematic technique, from black and white silent movie pastiches and stop motion collage to drawing that recalls our own Len Lye, all with a stilted jauntiness reminiscent of the pianola or autopiano (whose holes in perforated sheets the procession at the end appears to disappear into). There’s a constant movement, a tornado of energy that sees all ungrounded and swirling like Dorothy’s house in Kansas.

As the images tumble and anecdotes roll, sliding across each other, we watch Kentridge himself (in an odd nod to silent comedy) clambering over parlour chairs, as if trying to break time by going backwards. Relishing a human awkwardness, it’s as if he’s constantly, frantically, tripping over time as a piece of human furniture.

Within the layering, the soundscape is the strongest component (music from long-time collaborator Philip Miller). Kentridge himself is the key narrator, trying to keep up, like some conductor caught in a whirlwind where the pages of the score keep peeling off and filling the air.

Kentridge’s disembodied reverberating voice echoes through megaphones into the space, delays between the speakers stressing how time is reliant on the passage of waves through space. It’s as if you’re in the artist’s head - a dream full of delays, interrupted scenes and overlaid images.

The Refusal of Time is also the result of a collaboration between Kentridge and a Professor in Science and Physics, Peter Galison. The work might be considered a creative lecture on the historical shifts in our grasp on time, ranging from black holes and string theory to Einstein (read the excellent discussion between the pair in the handout first). Also running through the film is an underlying criticism of African colonialism and the cultural enslavement brought about by Greenwich Mean Time. Of making Africa dance to time. Yet this feels piecemeal and difficult to extract from within the work’s whirl.

At its best the work expresses a sense of how we try to connect with each other through time, and how we try to ground ourselves in the modern world through inter-personal transmissions: constantly checking our phones for new messages, crying out, waiting for a response, and in meantime just keeping breathing. It has great heart; the sense of Kentridge trying to make sense of it all, but in the end giving in to the centripetal whirl. It feels personal. It is touching and resonant.

Yet in its deliberate askewing of structure, spatial logic and time, the installation fails to fly. In its ambitiousness and collaborative fragmentation it undoes itself. It’s as if the artist remained too at its centre, failing to get sufficient perspective to compositionally make it really hum.

Mark Amery

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.