John Hurrell – 16 September, 2014

The ubiquitous 'rawness' means you can almost taste the dirt in your mouth or smell the smoky remnants of burning wood - induced by visual qualities that are not seductive. These are disturbing, confrontational photographs that are not about ocular pleasure but internal mental states. A geographic wilderness becomes a psychic ‘wild-ness'. Instead of panoramic tourist vistas we have the abject and bodily, peculiar (if not foul) images that reach inwards to frenetically shake - rather than look out to calmly admire.

The dry desert areas in the Californian region are an endless source of fascination for Kiwi art lovers. One of the hits of last year’s Auckland Triennial was Amie Siegel’s film (transferred to video) Black Moon (2010), set in the Californian desert, and one of the highlights of Bruce Philips’ fascinating exhibition Unstuck in Time, currently on at Te Tuhi, is the extraordinary film by the Otolith Group, Medium Earth (2013), that looks at the San Andreas Fault.

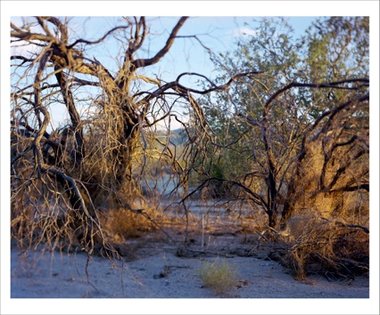

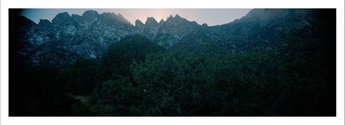

As with some of Joyce Campbell’s earlier shows, the botanical life of the Los Angeles region is of considerable interest to this artist, as are landforms and waterways - often seen in her New Zealand projects. Out of the Wash consists of a line of unframed photographs pinned lightly to the main long wall of Two Rooms’ narrow upstairs gallery. Her nine images centre around a road leading to a small town called Mecca, its turnoff being the site of a rest stop for truckers and a local illegal dump (with supplementary abandoned detritus collected by flash floods). The desolate sandy landscape, with its occasional clumps of tussock, is intermittently peppered with scruffy twisted trees, their stunted gnarled trunks accompanied by wiry ‘clouds’ of entangled dry leaves, pods, twigs and doubled-over branches.

What is interesting is the irony of the show’s title and just how unattractive these (seemingly) stunted dusty trees are, the perversity of their withered and parched arboreal settings as chosen photographic vistas to be apparently contemplated. The opposite of lush or romantic landscapes, Campbell’s wind-blown forms of woody vegetation are mixed with abandoned dirt-coated manmade rubbish of plastic, metal or fabric that is trapped within or alongside them. Some of the trees look black, leafless and dead, uprooted (possibly by floods) or even burnt. Compositionally a few almost look random, as if drawings incorporating swirling charcoal marks or rubbings - strange scratchy explorations of rotating energy.

These shots have quite a mood, one that goes further than desolation or mere dreariness. They are extremely raw, and have a gleeful repugnance, an aggressive viewer indifference, an in-your-face antagonism towards the niceties of element placement. In an odd way this suggests they are more about Campbell herself than the outdoor location or final exhibitable artefact. There is a sense of interiority, of process at work, almost like spontaneous graphic mark-making that is reliant on movements of the hand.

The ubiquitous ‘rawness’ means you can almost taste the dirt in your mouth or smell the smoky remnants of burning wood - induced by visual qualities that are not seductive. These are disturbing, confrontational photographs that are not about ocular pleasure but internal mental states. A geographic wilderness becomes a psychic ‘wild-ness’. Instead of panoramic tourist vistas we have the abject and bodily, peculiar (if not foul) images that reach inwards to frenetically shake - rather than look out to calmly admire. The image of the raven flying low over the road seems to confirm the ambience of the ominous trees, albeit less subtle and overtly melodramatic - as if Jason Greig has suddenly visited California. It’s an intriguing exhibition that is full of surprises.

John Hurrell

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.