Warren Feeney – 16 October, 2014

If there is one specific connection between the curious art of Brickell and Maseyk that unites them entirely, it is the legacy of the paintings of Michael Illingworth, an artist who in the 1970s was a neighbour to Brickell. Although it is questionable as to how reconciled Illingworth was to living on the land or getting back to ‘nature', the spirit of Brickell's art conjures up an intimate association with the Coromandel landscape that remains pervasive in Illingworth's paintings.

Dunedin

Barry Brickell

His Own Steam

13 September 2014 - 1 March 2015

Paul Maseyk

One Pot Wonder

12 July 2014 - 30 November 2015

An initial glance at the handouts for the survey exhibitions, Barry Brickell, In His Own Steam and Paul Maseyk, One Pot Wonder, might suggest differing perspectives about the attitude of both artists to vessels and pots. Brickell provides the gallery visitor with a 1970s-inspired, personalised A3 handout, while One Pot Wonder includes an elegant and modest contemporary catalogue with a concise gallery text about the artist’s practice.

Such differences might be expected because both artists are famous for the idiosyncratic nature of their work. Yet this deliberate pairing of exhibitions of their ceramics in the Dunedin Art Gallery confirms that these artists are thoroughly connected in spirit. Of course, Maseyk was mentored by Brickell and has identified him as an influence, so the decision to simultaneously include both shows in the same gallery is not inappropriate. In comparison to the vessels and pots of all their contemporaries, this pairing also directs attention to the work of two potters identified as ‘outsiders.’ (Sex seems to stalk the work of Brickell and Maseyk - it is all over their practice, either blatant or implicit). Maseyk assembles work that looks like pottery’s answer to the ‘geek-inspired’ paintings of Jess Johnson and Brickell’s vessels and containers act as an affectionate response to the paintings of Tony Fomison.

Brickell and Maseyk also share a presence as makers of large pottery and domestic ware. In His Own Steam and One Pot Wonder are about containers and vessels for the home. There is a scale that tends to take control of every room that they are placed in - and this further highlights a commonality of attitude. Both are indifferent to the expected or given limitations of their materials. Brickell forms terra cotta pots from coils on a scale that might have seemed impossible in the 1960s and Maseyk reinvents the surfaces of his pots using unglazed slip decoration as though he were working on stretched canvas.

How could a New Zealand potter like Brickell in the late 1950s, (admiring the refined aesthetics and self-imposed modesty of the Anglo-Oriental pottery movement), have responded from half way around the world with works so intimately connected to Melanesian and Pacific art and culture? And then there is the Driving Creek studio and home on the Coromandel hills with its train station and purpose-built track. Utilising clay deposits as the material of his practice and regenerating the bush and hillsides of the Coromandel via income from the sale of his pottery - Brickell’s practice and the Driving Creek Studio represents a conceptually rich and evolving arts project in which the boundaries between art and life are entirely blurred.

Maseyk’s One Pot Wonder brings together ten years of objects of surprise and wonder - not just in their scale and brilliance of colour or obsessive attention to detail, but in his democratic selection of imagery that takes in more than 3,000 years of Western art and history. Geometric Greek vases painting shares centre stage with war comics, and advertisements for sex are placed in the company of Matisse’s Woman in Blue (1937). Maseyk’s pots are commanding three-dimensional objects, domesticated and made intimate by their transformation as by-proxy canvases for images, patterns and designs that meander around their forms, all looking as though they are in the company of old friends.

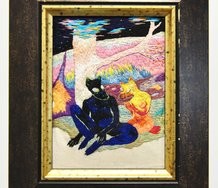

Yet, if there is one specific connection between the curious art of Brickell and Maseyk that unites them entirely, it is the legacy of the paintings of Michael Illingworth (1932-1988), an artist who in the 1970s was a neighbour to Brickell. Although it is questionable as to how reconciled Illingworth was to living on the land or getting back to ‘nature’, the spirit of Brickell’s art - drawing clay from the location and constructing pots and figures that radiate rebirth and fertility - conjures up an intimate association with the Coromandel landscape that remains pervasive (even if only as the subject of the artist’s desire) in Illingworth’s paintings.

And there is also that cheeky playfulness and mischief-making that typified Illingworth. The matter-of-fact full-frontal nudity and genitalia in a painting like Adam and Eve (1965), or landscapes occupied by silhouetted male and female forms, bonded to the natural world and procreation. In Illingworth‘s paintings, nature and humanity are both targets for full and frank disclosure, and Brickell and Maseyk have consistently made vessels and pots that are similarly out to provoke and unmask with an equally dismissive attitude to perceptions about good behaviour and manners.

Warren Feeney

Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.