Peter Dornauf – 14 April, 2015

Entering the gallery took on the feel of a glow-worm cave experience, being both simultaneously joyful and slightly unsettling. The rows of equidistant large dots came with a planetary aspect. Against each circle of paint was placed a second circle that became a satellite which from certain angles generated a 3D effect. From looking at what might have passed as stars in the night, the eye then moved across to the giant illuminated skull on the adjacent wall.

I Need You Bad. So sang B. B. King back in the late Sixties. Hamilton artist, Phillip Mcilhagga took up the chorus in his recent show at Pilot, painting the walls of the gallery in an installation of Op Art style pieces that covered the space from top to bottom, ceiling to floor. I need you bad was the title to a show that took four days to complete, but without any direct revelation as to who ‘you’ might have been. Perhaps at a guess ‘you’ could have been a suitable black light UV tube, since painting with day-glow paint in the daytime - even with the curtains drawn - is like painting blind.

But the effect and outcome was stunning. Gallery director, Karl Bayly, had hung white floor length drapes across the windows and door in order to enhance daytime viewing, however it was in the evening, after dark, when the full effect of the work was appreciated. Suddenly in the shadows, under the effect of UV lighting (situated along the floor directly beneath the works) things appeared as if by magic: notably the huge construction of a skull painted directly on the surface of the white gallery wall. Damien Hirst has a lot to answer for. Actually it was three skulls optically fused into one. Its presence was difficult to discern during day time viewing, despite the curtains.

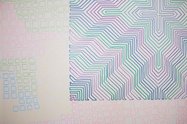

Optical illusion was one common thread here, something Bridget Riley first exploited, but Mcilhagga drew on a variety of eclectic sources in his re-articulation of Op Art forms and styles, taking elements from Frank Stella, the already mentioned Hirst and Riley - together with a touch of Sixties psychedelia.

This sampling approach, playing with visual language, created a kind of extraordinary light show that advanced on from Culbert and Hartigan. It was purely retinal with its configuration of lines, dots, swirls and geometric forms, although the presence of a figurative element in the form of the predominant skull, added an edge to disrupt the pattern, and confound expectation. Lines of regimented dots (circles) and skulls was Hirst’s trick but Mcilhagga’s direct juxtaposition of both images in one room on opposing walls - via day-glow paint - added another dimension.

Entering the gallery took on the feel of a glow-worm cave experience, being both simultaneously joyful and slightly unsettling. The rows of equidistant large dots came with a planetary aspect. Against each circle of paint was placed a second circle that became a satellite which from certain angles generated a 3D effect. From looking at what might have passed as stars in the night, the eye then moved across to the giant illuminated skull on the adjacent wall. These component elements thus became a clever play on obvious universal themes, tricked out in new colour effects.

Across the back wall there also snaked undulating structures made up of hundreds of drawn squares that exploited various colours from different highlighter pens. These organic forms contrasted with a Stella-esque geometric construction created by repeated triangular lines that radiated out from a central cross, forming three dimensional patterns. The final wall presented a large free-hand psychedelic swirl looking like something off a spinning firework, painted in silver but also reminiscent of the spiral arms of some galactic formation.

A variety of glowing colours were employed throughout the series - orange, yellow, green, peach, purple and chrome - adding to the pictorial effect. The fact that the images themselves appeared and disappeared under different light conditions contributed to the uncanny experience.

Galaxies, stars, skulls and ‘binary code’ dots (in a confined and darkly illuminated area) all had the potential to evoke meditations on the great subjects, especially when treated in a completely non-portentous way. While I need you bad might have initially been a reference to a “babe” in the original song, in this new context it seemed also to allude to some apposite philosophy to help the listener get through the night-time terrors of the enormities of space - those same horrors that so frightened the mathematician Pascal.

Peter Dornauf

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.