Sophie Violet Gilmore – 5 June, 2015

'swfer' takes pride in its intellectual difficulty by including three works which staunchly reference the dematerialising, disembodying processes of digital technology. Echoing the depthless surfaces of computer and cellphone screens, there is almost nothing in terms of aesthetic experience on offer, for the exhibition is calculatedly empty to the point of being depressing. Yet underneath the hazardously minimalist exterior lie fathoms of chilling conceptual intricacy.

The broad societal shift (in both the production and distribution of information) from analogue to digital over the past twenty years is something which many people seem terribly worried about. While the period when social interaction and media products had some material basis in reality is often nostalgically viewed as more trustworthy and sensible, the digital realm (computers; the internet and its technological agents) operating according to seemingly incomprehensible abstract processes, is perceived as hostile and unpredictable. Such anxieties are latent in the work of Luke Munn - a digital artist who has previously worked as a web designer and animator in both the corporate and arts sector - in his show swfer at the Blue Oyster Gallery.

swfer takes pride in its intellectual difficulty by including three works which staunchly reference the dematerialising, disembodying processes of digital technology. Echoing the depthless surfaces of computer and cellphone screens, there is almost nothing in terms of aesthetic experience on offer, for the exhibition is calculatedly empty to the point of being depressing. Yet underneath the hazardously minimalist exterior lie fathoms of chilling conceptual intricacy.

Each visitor to the exhibition probably absentmindedly uses a range of digital technologies every day, but by drawing out and making strange particular components, Munn seeks to make the viewer wary of their all pervasive presence. He is particularly interested in the relationship (or lack thereof) between the body and these technologies. The effect of digital experience on the body is investigated as a troublesome process of abstraction, codification and regulation.

The opening of the exhibition was accompanied (as is typical for Blue Oyster) by a performance work, this one - created by Munn - entitled High Touch. The piece, performed by Nada Crofsky-Rayner, involved her wearing headphones and quietly reciting an arbitrary sequence of phrases taken from tumblr.com each time another body brushed past hers. Reactions from the gallery’s visitors were tellingly varied, with some listening intently while others did not even notice.

As well as presenting the ironic possibility of digital code being run through the body instead of a purpose-built machine, and considering the frightening possibility of digital logic being seamlessly integrated into the body, the work highlights the innocuousness of internet interactions by contrasting them with affectively charged, real-world activity.

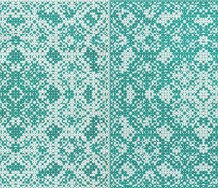

The incongruous relationship between the binary simplicity of the digital and the complexities of embodied human desire are neatly demonstrated in Code Swishing, a real time projection of a constantly refreshing (and functioning) webpage enlarged to display numerous three letter acronyms. Each pixel is hugely distorted, the colours encoded in the page disarticulated to an almost painterly effect.

These acronyms are inspired by those used in the (already nostalgic) personal columns of newspapers, in which particular phrases, being charged per letter, are abbreviated for economic reasons. Munn, however, conflates the phrases pertaining to solicitation with those which are simply condensed software names. In this way, the title of the exhibition, swfer, could relate to either ‘single white female’ or ‘shock wave flash’. Apparently, the codes cycle according to a particular pre-programmed sequence, but this sequence, like most of digital technology, is indecipherable and seemingly random in its function.

The ill-fitting condition of the digital, as an agent of human sexual interaction and its predatory aspects, is further explored by the piece, iChat, a link displayed in the gallery to simulate the kind of chat room set up by state agencies to lure and expose paedophiles. Conversations between various unsuspecting targets, who speak only with the letter ‘x’, and the invented 14 year old ‘Katy’, play out against a garishly feminine pink and leopard print background.

iChat demonstrates - along with the range of murky ways that sexuality plays out in the internet - the unique capacity for the digital to build simulated subjectivities which need no referent outside the workings of the technological apparatus. Through this work Munn demonstrates one of the more insidious tendencies of the digital world: that it makes possible, and also relies on, a kind of severance of the subject’s (or ‘user’s’) mind from their body, obfuscated through the apparent freedom and choice (in social and sexual activity) which it falsely appears to offer.

Throughout swfer, tiny elements related to the digital experience are played up and made mystifying, such in SeeDee, an audio recording of the white noise of a hardrive which echoes loudly and perpetually throughout the gallery. Along with the mantra-like audio recording, the artwork consists of a CD-Rom, perturbingly hosting an invisible trace of semen. Bodily activity spurred through digital use is shown as futile and perverse.

However, this aspect was not the reason why SeeDee was for me the most effective work in the exhibition. The display on a pedestal of the CD-Rom drive gave it a strangely anthropormorphic quality, the round CD slot appearing like a cycloptic eye, perhaps alluding to the way that we conceptualise computers according to the structure of our own minds, with ‘memories’ and ‘drives’. The mystical sense of a personality being connected to the CD-Rom through its display, brings to mind the intensely creepy computer ‘Hal 9000’ from Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: a Space Odyssey. This villainous computer perhaps acts as an ideal metaphor for the digital as Munn conceives of it: able to replicate human speech, emotions, and interactions despite only existing as bodiless software, and with an eventually murderous inability to negotiate its own programming.

A plethora of issues can be read into Swfer, pertaining to existence in the digital world, including the nature and possibilities of digitally-based artworks. One of the most interesting elements of the exhibition is that the gallery isn’t really where the artworks are located; instead the Blue Oyster venue acts like a router, an organizing hub through which the artworks intersect on their intangible pathways. The very slight physical presence of the artworks in the building (a web address made static as an inscription on a wall) perhaps attests to the limits of materiality which can be achieved in digital art. While the exhibition aims to shed light on and amend the seedy disjunction between the ‘user’s‘ body and their existence in the digital environment, it also makes clear the problems when attempting to reinsert the body into digital experience through art.

Despite illustrating the apocalyptic process of interpellation which the digital apparently inflicts upon each of its disembodied users, Munn offers no glimmering possibility of opposition at the end. There can be no ‘bright side’ to the digital for that realm is presented in swfer as a hypnotically closed circuit which can never be interrupted. Ultimately I was left to wonder if, like all forms of resistance to the transformative, compulsive logic of the internet, the exhibition, as clever as it is, falls into the same desperate trap of futility. By arguing so forcefully for the all consuming treachery of the digital, does Munn pre-emptively direct his works towards a meaningless destiny? Does he do this on purpose?

Sophie Violet Gilmore

Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.