Sophie Violet Gilmore – 29 September, 2015

The word 'sublime' in this case has presumably been adopted from Kant, and taken to mean something like 'the superiority of reason over nature'. To paraphrase Kant haphazardly, the 'mathematical sublime' relates to the sensation of reason's superior ability, when confronted with something empirically immense, to recognize the existence of infinity beyond the imagination's capabilities. With a particular type of wisdom, Thompson presents infinity as held together by sellotape.

Martin Thompson has become a recognizable figure around Dunedin since moving here from Wellington several years ago. Instead of staying hidden away in the mythical lair of a studio, Thompson can be seen almost everyday in a café or bar or bus stop on the main street, holding a pink folder crammed with papers, meditatively drawing. This kind of modified plein-air approach means that most of his works carry some trace of the environment they were produced in; forensic smears of coffee or cigarette ash or dirt exist on each of his works in pleasing counterpoint to their meticulous, calculated construction.

Thompson’s exhibition Sublime Worlds, his first presentation at the Dunedin Public Art Gallery, shows a variety of works he has produced since the mid 1990s, which grow increasingly zealous and ambitious. In 2005, his work was (quite appropriately) included in the American Folk Art Museum’s Obsessive Drawing exhibition. Since then, Thompson’s work has been shown in the Brett McDowell Gallery (on ongoing proponent of his work) and several other galleries throughout New Zealand.

Thompson is, according to the fashionable phrases, an “outsider” or “self-taught” or “visionary” artist, and in theory, the exhibition of Thompson’s work in a Public Gallery represents a critical point in his transition (or induction) into the art institution. Regardless, the compulsive nature of the drawings, their condition as a kind of personal intellectual exercise, gives the enjoyable feeling that even if Thompson’s work was never seen by anyone other than himself, he would continue methodically producing it. His reasons for creativity are entirely personal and sincere; the exhibition exists less as a controlled outward demonstration than an affecting immersion into an artist’s interior world.

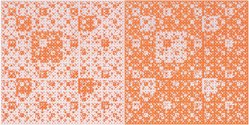

The works are all ink drawings (in a variety of electric hues of felt-tip pen) on grid paper. Particular sequences of grids are shaded in complex patterns devised by Thompson, who demonstrates, in each of the works, an idiosyncratic kind of mathematical genius, as well as a strict adherence to a personally created aesthetic code. Each series of works (or indeterminate size) is devoted to one colour, and each work is composed of two panels, a light and dark, or “positive” and “negative” version. The “light” panel is always displayed on the left, and whether the light or dark panel is the inceptive side in each work is one of the mysteries at stake.

A major development occurred some years ago in Thompson’s process, in which he started to cut out already-shaded sections of the paper with a scalpel and relocate them elsewhere with carefully applied sellotape. The artist reformulates the sequence of his pattern with each restructure of the medium, meaning, as in the case of Untitled (Blue), that these patterns can become bafflingly complicated. The gallery wisely chose to frame two drawings in reverse, to illustrate this technique. The artist clearly delights in complexity for its own sake.

The works, all named Untitled, readily summon to mind a variety of inorganic, non-natural metaphor. In particular, Untitled (Orange), with its sequential square forms, recalls the geometry of 80s video games like Pac-man, or the QR-codes on products or advertisements that you’re supposed to scan with a smart-phone. The alternating depth and flatness presented in the works, along with their systematic structure could be seen as a visualisation of the mind of a computer. This is particularly ironic, considering that some of us have seen the artist producing these works at first hand, a fact reinforced by the proudly displayed coffee-smears. Conversely, some of the works seem more closely (perhaps intentionally) aligned with the repetitive forms of nature. The sharp, shard-like forms of Untitled (Blue), together with its polar blue colour, reflect the mysteriously intricate and precise forms of snowflakes.

The obvious care and dedication involved in each the drawings is one of their most enjoyable aspects, and the repetitive, structured assemblage involved in each of them gives them a textile appearance. Some share certain similarities with the structure and devoted craftsmanship of William Morris designs. Apparently Thompson once said he thought his drawings would work well as wallpaper.

All of the Untitleds recall the child-like wonder of kaleidoscopes, as pure, unfurling geometric form, with the added difficulty, however, that they are rectangular - rather than circular to fit the eye. The shape of the paper works as a physical container for the abstraction of the patterns within, the page acting as a cross section of the possibility for infinite repetition which each pattern presents. While some of the works are determinedly static, others possess a purely optical potential for oscillation and movement. Untitled (Green) has a circular, mandala-like composition, in which layers of pattern appear to echo perpetually outwards from the centre, like the ripples around a fallen drop of water.

Seeing Thompson’s practice as a reflection on the nature of the infinite perhaps sheds light on the (profound, or just punchy) title of the exhibition, Sublime Worlds. His work certainly does immerse the viewer in its own, peacefully abstract world, possessed of its own fortified laws and conditions, a kind of environment for the eyes and the brain alone. The word ‘sublime’ in this case has presumably been adopted from Kant, and taken to mean something like ‘the superiority of reason over nature’. To paraphrase Kant haphazardly, the ‘mathematical sublime’ relates to the sensation of reason’s superior ability, when confronted with something empirically immense, to recognize the existence of infinity beyond the imagination’s capabilities. With a particular type of wisdom, Thompson presents infinity as held together by sellotape.

Given the increasing ambitiousness of the works over the period covered by the exhibition, and the artist’s evident proclivity for complexity, it will be interesting to see how Thompson’s work evolves in the future. Ultimately, the most exciting aspect of his work is that, without hesitation, the order of his microcosmic universe is fearlessly obliterated and recomposed through the incision of a scalpel.

Sophie Violet Gilmore

Recent Comments

John Hurrell

More sad news. Martin Thompson has died. He will be sorely missed. His wonderful graph-paper grid drawings are fascinating works. ...

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 1 comment.

Comment

John Hurrell, 7:50 p.m. 8 September, 2021 #

More sad news. Martin Thompson has died. He will be sorely missed. His wonderful graph-paper grid drawings are fascinating works. So unique! Bouncing around with positive/negative snowflakes.

https://www.stuff.co.nz/entertainment/arts/126320155/acclaimed-obsessive-artist-martin-thompson-has-died

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.