John Hurrell – 9 October, 2015

The two adjacent walls linking the two rooms feature paintings dealing with fragmented light so that when you look through the open doorway and compare, you can see on one side McCahon's dark fishing boats flickering on the blue sea (or pulsing balls of kauri blocking out the sun), and on the other, dappled light on the faces, arms and clothing of Henderson's women.

Auckland

Louise Henderson, Colin McCahon, Melvin Day, John Weeks, Wilfred Stanley Wallis, Charles Tole

Freedom and Structure: Cubism and New Zealand Art 1930 - 1960

Curated by Julia Waite

16 May 2015 - 6 March 2016

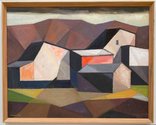

Right now in Auckland there are two exemplary New Zealand historic painting shows, exceptional not so much because of the individual items themselves (though they are exceptional) - but because of the way those items are positioned in the gallery space. Their placement is what is thrilling. One is the Laurence Simmons curated show of Gordon Walters gouaches at Starkwhite, and the other is this assortment of Cubist works at Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tamaki, researched and sequenced by Julia Waite, the Gallery’s assistant curator, and borrowed from various private and municipal collections.

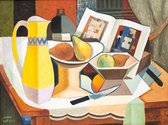

In two linked galleries on the second floor Waite presents forty-five works by the following six artists: Melvin Day (1923 - ), Louise Henderson (1902 -1994), Colin McCahon (1919 -1987), Charles Tole (1903 -1988), Wilfred Stanley Wallis (1891-1957), and John Weeks (1886 -1965). A big ‘landscape / cityscape’ room - split in half by a long partition - has thirty paintings by all six, while the adjacent smaller ‘ domestic interior’ space has fifteen by four (no McCahons or Toles). As a way of figuring out Waite’s thinking in terms of selection and balance, the numerical contribution (not spatial extension) of the individual artists goes: Henderson (17), McCahon (10), Day (6), Weeks (5), Wallis (4), Tole (3).

The two adjacent walls linking the two rooms feature paintings dealing with fragmented light, so that when you look through the open doorway and compare, you can see on one side McCahon’s dark fishing boats flickering on the blue sea (or pulsing balls of kauri blocking out the sun), and on the other, dappled light on the faces, arms and clothing of Henderson’s women. Because this show features a consistent intimacy where the viewer stays reasonably close, the works are sufficiently small to maintain a continuum between the spaces.

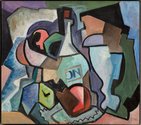

While most of these works (especially those by Henderson and McCahon) were made in the nineteen-fifties, the earliest painting here was made in 1929 (Weeks) and the last in 1971 (Tole). The show aims at presenting the (inevitably belated) impact of Cubism on New Zealand art, the first wave of radical anti-naturalism displaying the influence of Picasso, Braque, Gris, Metzinger and others, a difficult task for an exhibition to deal with when one considers, for example, that much of Weeks’ painting (the work of a crucially vital modernist pioneer) was destroyed in a fire in 1949.

Mixing in exceptionally informative wall labels, Waite provides a highly coherent and elegant orchestration of (Cubist-style) painterly-spatial treatment and subject matter. And while there are other artists who might be seen as Cubism influenced within this approximate time bracket - Rita Angus and Doris Lusk are conspicuous examples - Waite within her fresh examination of this period zeroes in on those she regards as working within ‘sustained investigations.’

The exhibition showcases a rich assortment of varied approaches to Cubism, and amidst the thematic discussions, sometimes curious little ironies occur within the biographical data. For example, think of the Walters Prize and these words which Weeks (the man who introduced modern art to this country) wrote in 1949, when already contemporary art was moving in a direction he regarded as elitist:

…fine art has been segregated far too much from the general pattern of life to be healthy, and has, in consequence, been placed on a pedestal for the benefit of the few rather than being the accepted and natural heritage of everyone.

The main benefit of the labels is that they set out clearly the connections the six artists had with each other, and each one’s different focus - and various shifts within it. Henderson, Day and Wallis learnt a lot from the older Weeks, while McCahon, though a supportive friend of Henderson, looked elsewhere and was beholden to Melbourne painter Mary Cockburn-Mercer. And despite Charles Tole likewise being greatly motivated by Weeks he was also profoundly influenced by other sources - the American painters Demuth, Sheeler and Hartley.

In this show you can circumnavigate the two rooms, matching up the same artists in several locations. Thus you can delve into their distinguishing characteristics, comparing with the others remaining in order to ponder the motivations behind the salient differences. In this country, these are some of the personalities that got the contemporary art ball rolling. A fascinating historical survey.

John Hurrell

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.