John Hurrell – 4 November, 2015

In looking at the drawn codifications, the conventions of graphically representing natural phenomena or human activities, it is fascinating to compare throughout the rendering of running water, flickering fire, airborne arrows, stacked up hacked bodies, or rows of fighting or obeisant figures. Precise repetition plays a crucial role, where many elements are identical and carefully organised.

Auckland

Indian miniatures from the National Museum, New Delhi

The Story of Rama

5 September 2015 - 17 January 2016

Exhibitions in New Zealand looking at significant aspects of India’s visual art culture are rare, but this richly informative display of over a hundred precious miniatures being presented in Auckland Art Gallery, is on its way home after a few months in Canberra. What a treat it is, for this is one of those rare multilayered displays (in the upstairs Wellesley wing, now painted glorious pink - with matching labels) that will fascinate those who enjoy a good narrative of conflict between good and evil, innovative design, the nuances of abstraction, manual dexterity by mostly anonymous artisans, and the unfolding of plots using structuring devices related to those found in comics.

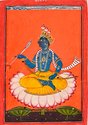

In up to the twelfth century Hindu visual images were confined to carved sculpture or temple murals. However with the advent of the Mughal invasion in the sixteen century (preceded by earlier Muslim invasions of the late twelfth century) came Persian influences, a tolerance of other religious traditions, and a love of books and portable images. These small pictures are amazingly varied.

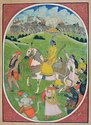

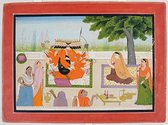

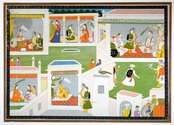

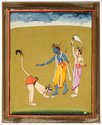

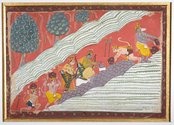

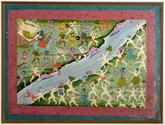

The original Ramayana epic is long and complex, in the manner of say The Iliad, but here its elucidation has naturally been drastically condensed - simplified in order to reach many communities. The hundred and one chosen works, made with opaque watercolour (and sometimes goldleaf) on paper - in their production - span the seventeenth to the nineteenth centuries, and have in their grouping and wall labelling been divided up into seven ‘books’ with the following themes: Childhood (the story starting within a poem by Valmiki, an ancient sage and hermit); The Kingdom of Ayodhya; The Forest; Monkey Citadel; Hanuman; War; The Next World. The main, constantly reoccurring, characters are Rama and his brothers (Rama is a version of the God Vishnu, and often has blue skin), his devoted (incredibly patient) wife Sita, the evil demon Ravana (spectacular with ten heads and twenty arms), and Hanuman the monkey king, with his snub nose and long tail.

Each of the seven carefully sequenced stories uses different visual permutations as miniature illustrations for key moments in the plot. There are over twenty styles or schools, their examples scattered throughout as intricate jewel-like images within the unwinding story. (In fact it would be fun to also see in another show the narrative dismantled, so that the styles did the structuring, regrouped via collective attributes, like say colour palette, compositional format, degree of complexity, degree of technical finesse etc.)

In looking at the drawn codifications, the conventions of graphically representing natural phenomena or human activities, it is fascinating to compare throughout the rendering of running water, flickering fire, airborne arrows, stacked up hacked bodies, or rows of fighting or obeisant figures. Precise repetition plays a crucial role, where many elements are identical and carefully organised. The images attain a musicality through the visual rhythms being deftly set up; spatially distant components interconnected.

The other eye-opener (related to the above) is how many works look unnervingly modernist in their spatial orientation (a few look like early Renaissance as well) - through the flatness of the picture plane connected to the use of aerial perspective, the awareness of apparent negative space (assuming that the paint hasn’t faded) and the oblique projection of rendered house walls. There is an obvious love of geometry in some, and darkened accentuating repeated shapes, usually with symmetry and counter-rhythms.

This is a deservedly popular show where the richness of what is on offer makes visitors reluctant to leave, or else leave planning further trips back. There are so many layers in terms of interpretive possibilities (the cultural significance of the stories themselves; the semantic ambiguities of the visual representations; the spatial and socially hierarchical conventions; the rendering of movement; the observation of animals, architecture and landscape; the mythical and cosmological symbolism) it is saliently worth it for out-of-towners to come to Auckland to see and think about.

John Hurrell

Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.