John Turner – 10 January, 2016

The academic activities linked to the opening of the Beijing Photo Biennial are particularly interesting and worthwhile, offering a wide range of speakers and insights into the complexity and contradictions of filtering photography through the one party political system that finances most of China's photography circles in one way or another.

Beijing

The Second Beijing Photo Biennial and Symposium

15 October - 29 October 2015.

I

Were it not for a blog to my wife by a Chinese participant two days before it started, I would have missed the opening of the Second Beijing Photo Biennial, themed Unfamiliar Asia and its associated Asian Wisdom academic symposium. Having missed the opening of the First Beijing Photo Biennial, Aura and Post Aura in October 2013, my enquiries to a number of people and institutions, including CAFA (Central Academy of Fine Arts) Museum, the main organiser, and its affiliate Three Shadows Photography Art Centre were to no avail.

Last-minute press releases seem another Chinese characteristic and The Three Shadows Photography Art Centre’s notice of their special Biennial contribution, Chinese Photography: Twentieth Century and Beyond arrived on 8 October, just a week before the Biennial opening. It made no mention of the Biennial itself that it was a part of.

This contrasts noticeably with the public relations awareness of the Lianzhou Foto Festival held in an out-of- the-way rural city in Guangdong Province, not to mention the publicity blitz surrounding the commercial Photo Shanghai fair. Following a presentation at Photo Shanghai, the Lianzhou Foto Festival also held a press conference in Beijing, in the 798 art district, at Ullens, on 12 October, with not only their director, Duan Yuting, present, but also this year’s guest chief curator, Christopher Phillips, from The International Centre of Photography in New York. Their festival, billed as Expanded Geographies, started on 21 November 2015 and ended on 10 December. Their English website with the unfortunate acronym (http://www.lipfart.com/) only lists the first five years of their festival (2005-2009) on the Invisible Photographer Asia website as of February this year. And the typically chaotic, overdesigned, Chinese only website: http://weibo.com/lianzhoufoto?sudaref=www.baidu.com#_rnd1445309365259 is not as helpful as it could be to fathom their offerings, but mouse clicks do take one to images from this and past festivals. The festival itself, unfortunately, seems to have given up running its own website.

II

The academic activities linked to the opening of the Beijing Photo Biennial were particularly interesting and worthwhile, offering a wide range of speakers and insights into the complexity and contradictions of filtering photography through the one party political system that finances most of China’s photography circles in one way or another.

The CAFA Museum is well designed, with a spacious lecture theatre adjacent to its cafe and ground floor exhibition areas, and CAFAM is a generous host, providing not only morning and afternoon refreshments for participants but also a packed lunch.

Keynote speeches were followed by a panel discussion, in turn followed by questions from the audience: all with expert translation to or from English into Chinese. Their programme and publications were also bilingual, to a high standard, so it must have been galling when one exception was a prominent visual backdrop that announced the ‘Asian Wisdom Furom’ on the Unfamiliar Asia theme.

Overall, the Second Beijing Photo Biennial encompassed CAFA’s Unfamiliar Asia exhibition, their Asian Wisdom symposium, and a library display, Photo Books: Chinese and Western Photography Publications and Chinese Pictures from the CAFAM Photography Collection, shown at 798 Art District. Linked events were From Pictures to Photographs: the Contemporary Chinese Photography Collection of Charles Jin, and Chinese Photography Since the Twentieth Century shown in the Caochangdi art district. The latter, Three Shadows Photography Art Centre’s survey exhibition, was scheduled for only one week, from 16 to 24 October, mainly for the mysterious Oracle Photo meeting of international curators of photography.

For this Biennial’s theme, Wang Huangsheng, Director of the CAFA Museum and Art Director of the Biennial, dated his programme introduction 10 October 2015, just five days before the biennial opened. This further indicates the whirlwind last-minute approach with which so many Chinese events seem to be completed. Preparations for this Biennial were said to have taken eight months.

“At the First Asian Art Museum Directors’ Forum held at the National Art Museum of China in 2006,” Wang Huangsheng wrote, “my talk focused on Asian boundaries and subjectivity. Within my limited scope of knowledge, the concept of ‘the region’ and the political consciousness of Asia has always been indistinct and diverse, embodying senses of both inferiority and superiority - How are the territories and boundaries of Asia formed? Who drew the lines? How should we as Asians understand the continent’s features and territories? What kinds of perspectives and psychologies from the major countries shape Asia, and how do we avoid self-centrism? Asia confronts a ‘strong’ West (Europe and America), whether we engage with the West or Europe and America, or their regional, cultural, intellectual, colonial, or economic ideas. What are most prominent are ideological symbols and the concept of politics. Therefore, how we “define” the concept and identity of Asia becomes uncertain, complex, and awkward. In addition, Asia’s diverse yet interlinked civilizations and histories, as well as rich and unique ethnic and regional cultures, create diverse values, religions, and customs. This rich yet confusing variety has been caught up in a net of inferiority resulting from superiority, and superiority resulting from inferiority. In today’s Asia, are we aware of our numerous problems? Or are we aware that we are aware of our numerous problems? These were the questions that inspired the curatorial team to propose the theme Unfamiliar Asia. (The curatorial team was composed of Yuko Hasegawa (Japan), Nili Goren (Israel), Chun Wai (Hong Kong), and Tsai Meng, Duan Jun and Wang Chunchen from Beijing, China.)”

Continuing his introduction Wang Huangsheng elaborates:

“Through an international photography biennial, we wanted to raise and respond to the questions of Unfamiliar Asia. We may be placing excessive burdens on photography as an artistic medium, and we appreciate the visual and intellectual responsibility photography carries. However, we believe that, because photography is a way of recording society, humanity, and reality, when photography meets the individual expressive methods of artists, the medium more directly and more sensitively records and expresses what we see and think. It provides a way to visually present observations and considerations of Asian reality.”

III

Unfamiliar Asia Thursday 15 October session

At 1.30pm there were brief formal introductions to the organisers and curators, given as part of a press conference, to start the Second Beijing Photo Biennial. That was followed by a lecture by Yuko Hasegawa, Chief Curator of the Museum of Contemporary Art, Tokyo. She presented a quick overview of the work on exhibition to the 200 people present, of whom most were CAFA students, I would guess. (Like CAFAM’s Foam symposium last year (see EyeContact, 6 November 2014) there was a noticable absence of academics from other Chinese Universities and of Beijing’s most prominent gallerists.) Hasegawa’s was a useful but light introduction that was given more depth in the following days by talks by some of the exhibiting photographers. Considering the historical political friction between China and Japan it seemed apt and slightly surprising to emphasise recent developments in Japanese photography under the rubric of Unfamiliar Asia to the predominant Chinese audience. Picking up on the upbeat ‘girls can do anything’ theme of Sputniko!’s delightul music video, The Moonwalk Machine - Selena’s Step Mrs. Hasegawa optimistically opined that if you want to change the World …. you can do it! (At least in your imagination? Like the ‘American Dream’ before it, the ‘Chinese Dream’, is a well-worn cliche here, and notably so in publicly funded art circles.)

Following afternoon refreshments, the exhibitions were formally opened at 3.30 pm. At 5.50pm participants were bussed to the 798 Art Centre for the opening of Chinese Pictures: from the CAFAM photography collection curated by Tsai Meng and Li Yaochen. CAFAM’s modest collection, started around 2000, consists mainly of gifts from alumni and friends, including work by recent graduates such as Zhang Chao, (who was featured in PhotoForum’s Momento magazine, No. 16, December 2014). As expected, there were some outstanding works on display by prominent Chinese practitioners. And also some mediocre examples. The panorama of Shanghai by Jin Jiangbo (known in NZ via Auckland’s Starkwhite Gallery) was not one of his best works, and the print of Marc Riboud’s 1971 image of a statue of Chairman Mao conducting huge smokestacks of pollution seemed to be a second rate copy, especially when compared to a run of immaculate small gelatin silver prints by CAFAM staff. The catalogue introduction to this modest but growing collection was too generalised to bear much scrutiny:

“In recent years, China has undergone immense changes. This ancient yet modern culture is profound, unique, and multi-faceted. Rapid development and tumultuous change have made China a focus for the world. In this process, too many artists have trained their lenses on China; some are Western photographers seeking out Chinese Utopian fantasies or sheer novelty, while others are internal observers taking critical and contemplative viewpoint. China is a very complex and very large place, so it provides photographers with rich pictorial territories and expansive visual fields. As a result, the pictures made in the land of China should be valued by Chinese museums, institutions, and individuals, which is the primary reason wanted to hold an exhibition of Chinese Pictures… This exhibition is a report on the state of the CAFAM photography collection, but the show also marks a new beginning.”

Included works came from the following (with some international guests): Shigeo Anzai, Cheng Tsun-Shing, Fu Yu, Feng Bingyi, Gu Zheng, Guo Shoutao, He Chongyue, Hiroji Kubota, 9mouth, Jin Jiangbo, Jiang Jianqiu, Jiang Pengyi, Luo Chaoqiong, Lu Heng, Liu Xiangcheng, Ma Yongqiang, Marc Riboud, Qu Yan, Shao Wenhuan, Angela Su, Tian Xiaolei, Wang Guofeng, Wang Ningde, Wei Lai, Weng Naiqiang, Wu Jianxing, Wang Chuan, Agnes Varda, Yao Lu, Yang Tiejun, Yu Fei, Yan Baoshen, Yu Xiao, Zou Shengwu (Yanzhang), Zhang Yuming, Zhang Chao, Zhang Dali, and Zhang Kechun.

The final destination for the evening was a large popular 798 restaurant where I was seated next to the Israeli photographers, Boaz Aharonovitch, Shai Kremer, and Gilad Ophir. This should be interesting, I thought, because I am a member of Auckland’s Palestine Human Rights Campaign in Auckland, and very much against the occupation of Palestine. Aharonovitch, Kremer and Ophir, however, proved not to be blind Zionists but decidedly critical of their country’s brutal aggression under the guise of defence. It had seemed strange to me that Israel was represented so prominently at both of Beijing’s Photo Biennials to date, but discussing this with Bas Vroege, the Dutch chief curator of the ‘international’ facet of the first Beijing Photo Biennial, Israel’s continued occupation of Palestine was high on his list of priorities for showing how photographers deal with violent racial-political conflict. Seemingly oblivious to the momentum of the Boycott Israel movement, or because of it, the Israeli embassy has continued its support of the Biennial.

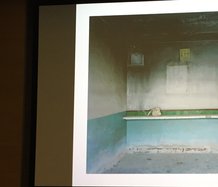

The work of Kremer and Ophir, in particular, is critical of Israel’s military dominance and their occupation of Palestine. They provide visual evidence as notes of these ‘facts on the ground’ but offer no solutions to ending the conflict but did agreed that the concept of two countries (as against the one country concept), has passed its use by date. What China learns from the Israeli-Palestine war is difficult to fathom, because Israel still seems to get favoured nation treatment here.

John B Turner

Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.