John Hurrell – 14 February, 2016

In this complex interwoven (but strangely disjointed) essay Steyerl looks at the current (admirable) impatience for profound social change globally, mentioning how judging from statistical analysis by Google Books of word usage in publications in eight languages, since 1920 the use of the concept ‘impossible‘ has halved. Fatalism and negativity has markedly decreased and obviously been replaced by resolute determination.

Auckland

Hito Steyerl

Moving-Non-Moving Images Lab (Duty Free Art)

11 December 2015 - 17 February 2016

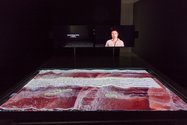

This installation by Berlin-based filmmaker and writer, Hito Steyerl, is a presentation of a recent video that involves two vertical screens (the artist speaking on the right: diagrams, maps and quoted texts on the left), and on a low table in front of the viewer, a sandpit tray on which are also projected (from the ceiling) diagrams, maps and texts - but moving.

Duty-Free Art, her forty minute lecture, is in nine short chapters. Here is a transcript of this zigzagging but very interesting discussion, with some of the accompanying non-moving images.

In this complex interwoven (but strangely disjointed) essay Steyerl looks at the current (admirable) impatience for profound social change globally, mentioning how judging from statistical analysis by Google Books of word usage in publications in eight languages, since 1920 the use of the concept ‘impossible‘ has halved. Fatalism and negativity has markedly decreased and obviously been replaced by resolute determination. Although Immanuel Kant (in Steyerl’s - perhaps questionable - explanation) insisted that time and space were crucial elements to underpin any discussion of anything, Steyerl in her discussion of ‘conditions of possibility’ takes a recent description of contemporary art by the British philosopher Peter Osborne and expands it, emphasising a fictional layering of time and space where there is no accountability, only the use of multiple sites (in transit zones) beyond national borders.

She then zeros in on freeports, tax havens for art collectors who hide caches of art works in ‘neutral’ zones beyond nationality (‘cages without borders’), places like the storage facilities of airports or ‘extraterrestrial’ warehouses of Switzerland or Singapore.

One of the fascinating themes Steyerl draws out is what she calls ‘the PR equivalent of a nip and tuck’ that the Syrian regime uses to ingratiate itself with western cultural institutions such as the Louvre, the Guggenheim Bilbao or the British Museum. Presenting apparent (pre-civil) war correspondence between the studio of celebrity architect Rem Koolhaas (and Richard Rogers too), and officials representing the Assad family, now seemingly made public by WikiLeaks, Steyerl showcases the difficulties of knowing for sure whether these documents are genuine, and discusses the impact of the hacking projects of opposing Syrian groups like the pro-Assad Syrian Electronic Army and the rival faction Anonymous Syria.

While Steyerl seesaws back and forth in her discussion (awkwardly skipping from topic to topic) so you wonder where she is going next, the last chapter is a sort of verbal pun on duty-free art, (a parallel with visual puns that she sets up, blending Osborne’s philosophical diagrams with bombsights):

duty-free art ought to have no duty - no duty to perform, to represent, to teach, to embody value. It should not be indebted to anyone, nor serve a cause or a master, nor be a means to anything. Duty-free art should not be a means to represent a culture, a nation, money, or anything else. Even the duty-free art in the freeport storage spaces is not duty free. It is only tax-free. It has the duty of being an asset.

…But autonomous art could even be art set free both from its authors and owners.

Here she is discussing two museums in Turkey and how they are functioning in ways far beyond the intentions of their architects when built. One is the municipal art gallery of Diyarbakir that she mentions at the beginning and which became an emergency shelter for Syrian refugees, and the other is the museum in Suruç, also turned into a refugee camp. We see in the latter that she has photographed a man looking up into the sky with binoculars, searching for Syrian bombers. In an ironic sense the new forms of art gallery have acquired the beneficial properties of freeports, are geographically shattered and are beyond national boundaries. The Suruç example is in Turkey, but also in the identically named autonomous canton of Kobanê that is situated in Northern Syria. The conventional borders have dissolved, and the shape of the split open territory unfinalised.

Although her subtlety might prevent you from grasping it at first, such fluidity goes well with Steyerl’s downward projections on the sandpit in this show (the mounds alter as curious visitors rake their fingers through the sand), a very clever extension of content into form where segmented discussion, spatially ambiguous diagrams and teaching aids merge.

John Hurrell

Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.