Andrew Paul Wood – 1 May, 2016

The trendy reading would be to position Harris' paintings as some sort of compromise between traditional concepts of beauty and the uncanny. While this isn't particularly inaccurate, it's also over-egging the pudding slightly. The pleasures inherent in the act of applying paint to a surface justifies itself, as do the forms - part naturalistic, part automatic doodle - which extrapolate themselves into these elaborate compositions.

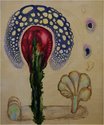

The title of Rebecca Harris’ exhibition at Chambers 241, Pink Sugar Bush, was partly inspired by a 1970s book on proteas - those ancient African dinosaur shrubs that seem as much bird as flower - as are the paintings in all their biomorphic fluorescence. Both paintings and title also both contain a hint of the vulval and vaginal. Georgia O’Keefe on some funky acid. There is a strongly self-conscious, recherché quality to the work, dipping into and synthesising a richly diverse set of forebears and archetypes. Perhaps they’re passports into the Swedenborgian Space of the Spirits.

Each painting is precisely structured around organic rounded forms of translucent colour that remind one a little of the poured varnishes of Harris’ near contemporary at Ilam, Marie le Lievre. On one level there are suggestions of the atmospheric, lyrical, broad other-worldly vagaries of Odilon Redon and Marc Chagall, but then the eye is quickly drawn into the details as though looking at an intricate illustration in a story from the Brothers Grimm or a Victorian fairy painting. There are hints of Max Ernst, Samuel Palmer, Arcimboldo, Bosch, the spiritualist outsider artist Madge Gill, cellular microbiology and even the Voyinch manuscript. No doubt other viewers will be able to furnish their own list because it’s work that lends itself to a rapid stream of thoughts and impressions. That diversity makes it really difficult to categorise or label, which may make it an awkward commercial sell, but it’s that flamboyant miscegenation of sources that appeals to me.

It’s a celebration of the life force principle, a painterly equivalent of Walt Whitman’s “bardic yawp” without the utopian political pretentions. Iä! Shub-Niggurath! The imagery quivers and pulsates luridly, obscenely with it in some cases, but not quite as brightly or in the same pure colours as Pat Hanly. What may have started out in the forms and textures of the humble protea have been transported to an altogether alien, science-fictional planet of polyps and pseudopods entirely. Early pioneering abstractionist Hilma af Klint came to similar technical and formal conclusions in her attempts to diagrammatise invisible inner and outer cosmic forces. The paintings tease at the suggestion of figuration in their ultimately self-contained dream worlds that subvert the expectations of the decorative and ornamental.

These days the work seems to be moving away from the territory of Glenn Brown and Christian Rex van Minnen into something more delicate and formalist, less melting ice cream, more Louise Bourgeois. The Lovecraft-on-Haight-Ashbury psychedelic affectations have been dispensed with (though a suggestion of Heinz Edelmann’s Yellow Submarine bulbousness asserts itself) in favour or a more art-historical sensibility firmly anchored in the Symbolist modernist avant-garde. The compositions are cleaner, lighter. The mannerisms of Redon, often commented on in Harris’ work previously, are still there, but digested into a synthesis with the dense drawing of Unica Zürn and formal logic of Roberto Matta.

The trendy reading would be to position Harris’ paintings as some sort of compromise between traditional concepts of beauty and the uncanny. While this isn’t particularly inaccurate, it’s also over-egging the pudding slightly. The pleasures inherent in the act of applying paint to a surface justifies itself, as do the forms - part naturalistic, part automatic doodle - which extrapolate themselves into these elaborate compositions. Again, another kind of growth and fecundity. Harris’ paintings appeal for their enthusiasm, their verve and chutzpa, and the wonderful obsessive precision of her detailing. It’s powerfully poetic stuff that tumbles out of the artist’s imagination and sings off the surface.

Andrew Paul Wood

Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.