Will Gresson – 1 November, 2016

As recently as 18 months ago, new research revealed that mealworms were able to safely digest and compost Styrofoam, something that for many years had been perceived to be resistant to biodegradation and consequently one of the most ecologically damaging materials from a conservation point of view.

In Percy Bysshe Shelley’s Ozymandias, the celebrated poet describes the remains of a statue out in the desert, as told to him by a traveller from an “antique land.” Across the piece’s two stanzas, he juxtaposes the fearsome might of the ancient titular King (the Egyptian pharaoh Ramesses II, here identified by his Greek name) with the weathered decay of the statue itself. Looking at GREENHOUSES, Aude Pariset’s new body of work currently showing at Cell Project Space in London, the words inscribed on base of the statue immediately come to mind:

My name is Ozymandias, king of kings:

Look on my works, ye Mighty, and despair!

It’s a bold threat, made from a position of great authority; a singular statement of total dominance and unrivalled power. It is also beautifully contrasted by Shelley in the poem’s final lines:

Nothing beside remains. Round the decay

Of that colossal wreck, boundless and bare

The lone and level sands stretch far away.

The hubris of human endeavour and pursuit, laid bare by the inevitable passage of time, is increasingly interwoven with our discussions about Global Warming and the Anthropocene. We are simultaneously aware of our own unavoidable demise, both individually and ultimately collectively, and yet we attach the utmost importance to the creation of physical and metaphorical statues and ornaments, mere trinkets perhaps one day to be found in the shifting sands of a desert by those who come after us and wonder what all the fuss was about. At the same time, this awareness of human fragility and in particular the effect of human endeavour on the natural environment means we now find ourselves at a moment of incredible technological development in terms of environmentally conscious research and practice.

In GREENHOUSES, perhaps the most striking element of the exhibition owes much to this increased awareness and investigation. On the floor of the two gallery spaces, sit two repurposed Ikea bed bases fashioned into makeshift vitrines. Both contain blocks of Styrofoam being slowly demolished by a colony of mealworms. As recently as 18 months ago, new research revealed that mealworms were able to safely digest and compost Styrofoam, something that for many years had been perceived to be resistant to biodegradation and consequently one of the most ecologically damaging materials from a conservation point of view.

To suggest that these works represent a heavy handed evocation of the idea that we are all, in the end, ‘eaten by the worms,’ is to understate the importance of the turn that is happening here. While in Shelley’s poem, time is the great enemy that ultimately achieves the King’s destruction, here time becomes a weapon; a way to mitigate the damaging affect these man made materials have on the natural environment and transform ‘decay’ into a positive force for continued survival.

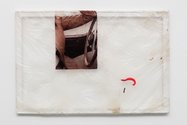

This idea is heightened by a series of framed works installed across the wall of the larger space, with a single larger work hanging in the small back space. Again featuring repurposed materials (stock picture frames rather than traditional painterly frames for canvas), these works are made using hand-made bio-plastic, and what appear to be collaged magazine cuttings. The images are all slightly disconnected photographs of luxury items (fine clothing, a groomed horse, the wheel of a luxury yacht), their futility emphasised by the negative space of the plastic which appears somehow decayed, as if yellowed with age or previous use. They symbolise wealth, attainment, the celebrated acquisition of the signifiers of ‘the good life.’ It’s a demonstration of wealth that has since replaced the once exclusive power of royalty like the long-dead Pharaohs, but one which is portrayed as equally ephemeral in these delicate and semi-transparent works.

Bookending the works are two simple black archivist’s wheels, found on old library bookshelves to help search through material. These two items are so small one might almost miss them on first glance, yet their highly loaded presence brings many of the exhibition’s central concerns to the fore. From a historiographical point of view, they symbolise the way we increasingly understand archives and history as a body of constructed narratives, rather than merely unbiased, factual accounts. In the same way that we scour an archive to find the sources which best fit our case, so too do we reconstitute our past to carefully curate our present. Time can be malleable, and as such, can be both a blessing and a curse depending on our particular agenda. The wheels also offer a subtle contrast with the wheel of the luxury yacht found in one of the framed works. Whereas the yacht speaks to a false hope of longevity, the accumulation of wealth and the pursuit of leisure activities, the archivist’s wheel perhaps is the real symbol of what might ultimately define us.

In collaboration with the artist, Laura Preston has written a beautifully lyrical text that serves as both an entry point to the exhibition and an opportunity for critical reflection. In one figure, she discusses ‘the Mechanism,’ an object discovered in a shipwreck off the cost of Antikythera by divers around 1900. The object is believed to be a way for the Greeks to understand the world around them, described here by Preston as a kind of time machine or perhaps a clock. “As with a clock it offers a way of rationalising natural phenomena by superimposing a series of dials upon the sky,” she writes, “and without needing to cast a shadow.” The link between ‘the Mechanism’ and the archivist’s wheel is clear, but Preston acknowledges this by also referencing a statue of Hercules found alongside the mysterious object: “he once symbolised the overcoming of earthly desires (if that is at all possible) and the earth itself as a consumer of bodies (could the opposite also be said?).” In contrast then, she writes “the recovered Mechanism shows a much more sympathetic relation to the earth, reading it’s fluctuations and acknowledging its cyclic (biodegradable and regenerative) nature; an ethics that may be extended to working with the archive.”

From a curatorial standpoint, the works feel like they fit in with some of Cell Project Space’s previous exhibitions. It’s tempting to draw parallels between the concerns of Pariset’s GREENHOUSES and other “post-internet” artists like Yuri Pattinson or perhaps Harry Sanderson, with their focus on the way technological advancement has influenced our construction of images, or the narratives we tell ourselves. Thematically perhaps, it feels the most similar to the group show m-Health, which saw several artists responding to “aspects of our changing social and natural environment and the responsibility we have towards it.” Ultimately however, Pariset’s work also feels separate from these by way of their fragility and formalist elements, as distinct from the slicker presentation of her digitally engaged peers. Perhaps it’s simply an acknowledgement that one day, nothing will remain of these objects either.

Will Gresson

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.