John Hurrell – 27 August, 2017

What is a little surprising about this exhibition is the high percentage of painting or drawing, and lack of interest in moving image. There is an emphasis on manual manipulation or touching of materials, with some deferral achieved via selection of other artists' work.

Auckland

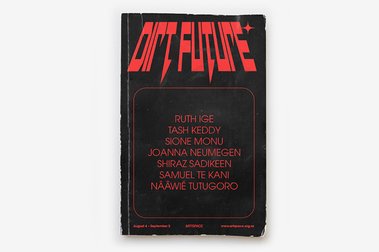

Ruth Ige, Tash Kennedy, Sione Monu, Joanna Neumegen, Shiraz Sadikeen, Samuel Te Kani, Nââwié Tutugoro

Dirt Future

Curated by Bridget Riggir-Cuddy with Cameron Ah Loo-Matamua

4 August - 2 September 2017

This show is an annual project constructed to present work from new artists in Artspace, this time between the departure of one director and the arrival of the next. The seven individuals have been organised by Bridget Riggir-Cuddy and Cameron Ah Loo-Matamua to create a nicely organised space, with each contribution given lots of room, and an annex out the back with a heaped table presenting relevant research material, artists’ notebooks—and a wall displaying some working drawings. The title of the show has a clever ambiguity: it could be about death and the burial of our species; it could be about a globally developing agrarianism.

What is a little surprising about this exhibition is its high percentage of painting or drawing, and lack of interest in moving image. There is an emphasis on manual manipulation or touching of materials, with some deferral achieved via selection of other artists’ work.

Nigerian Ruth Ige’s dark toned oil paintings celebrate her own skin colour by rendering parts of her umber body amongst views of worn clothing and glimpses of room décor. As politicised objects they use fragmentation and gesturalism to respond to Auckland-as-Place via a contextualised mood of alienation and disquiet, and tight technical control of the medium.

Shiraz Sadikeen’s rollable vinyl paintings and ‘laminated’ drawing constructions seem to represent two different poles: one spacious and airy; the other compacted and dense / one coloured, shiny and thin; the other grey and white, matte and thick. The organic paintings—with blobby and blank human-caterpillar’ faces—contrast vividly with the ultra-obsessive, intricate, multi-scaled rows of doodly ‘maggot-people’ drawings or print-outs on pads. The work seems vaguely related to that of Susan Te Kahurangi King, but although it has loose, spontaneous sections, overall it is much more preplanned, grid focused and preoccupied with different sized modules.

Nââwié Tutugoro contributes two subtle site-specific ‘sculptural drawings’ made of fabric, one a blue tarpaulin that dominates the gallery ceiling with a watery cobalt expanse, and the other, a loose silver ‘safety cloth’ suspended from a wall in a nearby room, and which—using an electrical fan—flaps and clicks noisily. No handmade marks here, the work is all about positioning and aural, kinetic or extensional domination of space.

The large, ‘notepaper-lined’ painting by Joanna Neumegen, with its rubbed-on tiger balm, ironic self portrait and attached angel wings, provides tropes for personal freedom and release that act as foils for the symbols of exclusion and obstruction she has placed on the other side of the wall: a grilled security window and door. A clever device using the partitioning wall as a kind of conceptual fulcrum.

Tongan artist Sione Monu is usually known as a photographer. His images are currently on display at Fresh and will then come to the new Objectspace. In Artspace four abstracted landscape drawings from him show small flaglike rectangles swirling out of the sky and over the land, the abstract remnants of an earlier series on Pacific bodies. The pastel drawings, his Untitled Mana Woman series, are anti-narrative—calculatedly thwarting bodily representation and interpretation—though if some of the earlier works (done with the Witch Bitch collective) had been included, the later conceptual and formal development might have been clearer.

The Garden of Failure, Samuel Te Kani’s sculptural installation, with its dark illumination, wonky lettering, extinguished candles and general ambience of awkwardness and rejection of finesse, has an angular carved ‘Polynesian’ god in a shrine, gradually being covered with vines and flickering LEDs. Its conspicuous fatalist mood fits the atmosphere of much of the remaining show with its stringy, splintery, hacked-out doorways and raw pencil work.

Shortland Street’s transgender actor Tash Keddy’s corner installation presents various portraits and cityscapes by artist friends on the walls, and a table raised high on a stage, laden with rotting fruit. The assorted proffered delicacies, now growing furry with mould and suppurating, reflect the juxtaposing graphic processes of other contributors like Shiraz Sadikeen, the much faster physical movement of Nââwié Tutugoro’s architectural modifications, and the frayed entrance-way textures of Joanna Neumegen; a subtle ‘mirror’ in sympathy with the rest of the show.

John Hurrell

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.