John Hurrell – 27 October, 2017

The eighties oil paintings seem to have conceptually grown out of a series of coloured xeroxes made in 1978 by photographing a rat running over the stomach area of her naked body. The canvases (with their turgid, over-wrought and dense surfaces) don't hold up well thirty years later, but to do them she made fabulous spontaneous drawings on paper with ink and watercolour that still look fresh. Her airy, loose sketches featuring women and rats are the show's highlights.

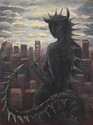

The late Alexis Hunter was hugely admired for her influential pioneering feminist photography, narrative storyboards, and photorealist painting works of the mid seventies, and although she caught the Neo-Expressionist painting wave of the eighties with her frenetic, cathartic and decorative mythic animals series (mythical creatures and women in violent conflict or passionate love making) which brought her a wider audience, the early works-in my view—have a more memorable, startling profundity.

An Elam graduate who moved to London in 1973 and married a publican, Hunter died prematurely three and a half years ago, and so this show is a sample of her art practice, a cross-section—it turns out—of her various strengths and weaknesses.

The eighties oil paintings seem to have conceptually grown out of a series of coloured xeroxes made in 1978 by photographing a rat running over the stomach area of her naked body. The canvases (with their turgid, over-wrought and dense surfaces) don’t hold up well thirty years later, but to do them she made fabulous spontaneous drawings on paper with ink and watercolour that still look fresh. Her airy, loose sketches featuring women and rats are the show’s highlights.

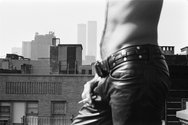

Paradoxically when Hunter handles oil paint, her technique is much more successful in the earlier, very tight, black and white photorealist works that celebrate the (heterosexual) female gaze enjoying the lithe tattooed bodies of construction workers or motorcyclists. Only the working photos for those works are here.

Looking beyond her surface qualities, with Hunter’s oil paintings the images fit generally into a psychodrama embraced by other neo-expressionist painters such as Ken Kiff or Davida Allen, but much more knowing in terms of gender politics and distance from the subjective self. Fierce, righteous indignation is mingled with feral archetypes, double-entendre and self-aware irony.

Of her photos, the early seventies suite, The Model’s Revenge is impressive with its menacing ambivalence, and allusions to a desired female model in a bedroom. It suggests anger at male objectification, mixed with resentment of the contradictory forces of desire and brandished power—with guns as glistening fetish items. These weapons double as phallic symbols and tropes of suppression, but now turned against the oppressor.

Hunter’s extraordinary confidence with her graphic skills, involving deft rendering of facial expression and body language (of symbolic animals as much as humans) are what makes this show worth checking out. The photos are really good but the drawings on paper are sublime. Miles cheaper (if you want to own one) and infinitely superior to the eighties oil paintings.

John Hurrell

Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.