Andrew Paul Wood – 2 February, 2018

Fahey's adoption of the heroic mode for the domestic is a powerful gesture of pragmatic feminism, for while one wants to avoid clichéd generalisations about art by women in the 20th century, certainly in New Zealand the careers of women artists tended to be restricted to there until the 1970s. Treating a family spat like it was 'The Oath of the Horatii' is a surprisingly, presciently postmodern deconstruction of traditional art historical ideas about gender, hierarchy and genre.

Christchurch

Jacqueline Fahey

Say Something!

Curated by Felicity Milburn

22 November 2017 - 11 March 2018

Till Homer’s ghost came whispering to my mind.

He said: I made the Iliad from such

A local row. Gods make their own importance.

—Patrick Kavanagh, Epic

Without a doubt my favourite show of the Christchurch summer is Jacqueline Fahey: Say Something! at Christchurch Art Gallery, curated by Felicity Milburn. It’s a lovely example of the relatively compact survey show, and, coinciding with Ann Shelton’s Dark Matter means that CAG is a bit of an ex-Timaruvian fest. In some ways the show forms a sort of coincidental companion to (and shares a couple of works with) another Fahey survey, Where My Eye Leads at Te Uru in the first part of 2017, but that show mainly focussed on the 1990s less well-known work whereas this show is more of a ‘greatest hits’ with an emphasis on Fahey’s fecund 1970s period.

Born of Timaru Irish-Catholic stock in 1929, Fahey studied painting at Canterbury University College (as it was then) School of Art, from which she received her Diploma of Fine Arts in 1952. She was married to Fraser McDonald, a high-profile psychiatrist, until his death in 1994. One wonders if that was an influence on her intensely psychological paintings.

Fahey’s contribution to New Zealand art has been well recognised: an ONZM in 1997 and a New Zealand Arts Foundation Icon Award in 2013. Internationally her work was acknowledged by inclusion in the 2007 survey of feminist art WACK! Art and the Feminist Revolution at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles, USA. Her two volumes of autobiography, Something for the Birds (2006) and Before I Forget (2012), are well worth reading.

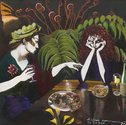

My first Fahey was probably Sisters Communing II (1990), which I would have seen in the collection of Aigantighe Art Gallery in Timaru—from the French Bay period, Fahey’s daughters consoling each other like something out of Greek tragedy, in thick impasto over a collaged in meal clipped from a magazine, against the backdrop of a flamboyant ponga fern. The impasto in Fahey’s works rarely conveys well through photography.

My favourite Fahey is almost certainly My Skirt’s in Your Fucking Room! (1979, Collection of William Dart — of course it is), full of fantastic drama and expression. Both works are in the exhibition and evidence her peculiar gift to take domestic and everyday drama and elevate them to the status of full-blown epic history painting. Suburban Kiwi womanhood apotheosises into Clytemnestra, Electra etc. In that sense it anticipates (but not by much) the classically-inflected postmodernism staked out by American critic Charles Jencks.

Taking his cue from architecture, Jencks defined postmodernism as a counterreformation reacting against modernism by looking back to academic historical humanism in the form of classicism. Of course this was also a terribly flawed way of looking at the postmodern fragmentation of taste hierarchies because it just swapped modernism’s romantic obsession for the transcendental with neoclassical rationalism, and also ignored that formalist modernism frequently drew on classicism anyway.

At any rate, Fahey’s adoption of the heroic mode for the domestic is a powerful gesture of pragmatic feminism, for while one wants to avoid clichéd generalisations about art by women in the 20th century, certainly in New Zealand the careers of women artists tended to be restricted to the domestic sphere until the 1970s. Treating a family spat like it was The Oath of the Horatii is a surprisingly, presciently postmodern deconstruction of traditional art historical ideas about gender, hierarchy and genre. The personal is political, as the old rallying cry of second wave feminism went.

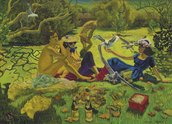

The art-historical awareness is to the fore in Luncheon on the Grass (1982), which is a gender-swap of Manet’s Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe, with clothed women discussing the best bits of the objectified male nudes in a New Zealand urban park setting.

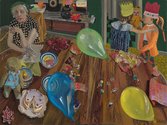

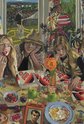

At times the human actors are thrust right to the edge (but not out of) awareness as in The Birthday Party (1974, Victoria University of Wellington Art Collection) which uses an almost lenticular anamorphic distortion to concentrate the viewer’s attention on the debris of a child’s birthday tea—the balloons are magnificent. The young girls in their paper hats, off to the left, are fully engaged in their own play and each other, while an older woman stares out of the picture plane—youth, age, and memento mori.

Such perspectival distortions are a reoccurring feature of Fahey’s work, contributing to their peculiar emphases and unheimlich atmosphere of unease.

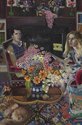

Many of the paintings are very much of ‘women’s space’ as it existed at the time. They aren’t all dramatic. In Sisters Communing (1974, Hocken Collection, University of Otago) the subjects sit contemplatively, one breaking the fourth wall by meeting the gaze of the viewer with a similar expression to the server in Manet’s A Bar at the Folies-Bergère. They are as hieratic as a couple of Faiyum funeral masks. The young girl, playing with her rag doll on the floor, is entirely oblivious to anything else.

In this painting it’s the setting that does most of the acting, and not incidentally, dates it like a kind of time capsule—things familiar from my childhood with which the subjects are adjacent, but somewhat theoretical. A typical suburban Axminster of the time is translated to Orientalist Ottoman fantasia. The bobble rug has an expressionistic richness and depth. The fireplace is a real, recognisable fireplace, and the sack of coal has a legible label of a known brand.

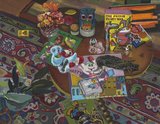

It’s those little trompe-l’œil flourishes, like the bag of ‘Cosy Coal’ and the opened letter from the QEII Arts Council in My Skirt’s in Your Fucking Room!, that anchor the mise-en-scene in time and place, and perhaps, in a similar trajectory to Picasso, leads to the incorporation of collage into the paintings. Indeed, the exhibition includes an example of Fahey’s earliest surviving work, Woman at the Sink (1959, a possible allusion to John 4 perhaps?) in which the artist wields the elements of synthetic cubism far more confidently than many of her male contemporaries.

What isn’t present is anything from the K’ Rd series from the early 2000s with their Bosch-like hell-scapes of pedestrians, cars, and outbursts of random violence. This is perhaps for the best as the deliberate disjointedness those late works wouldn’t have gelled with the classical unity and gravitas of the present selection.

I could pad this out with any number of superlatives, but really all that needs to be said is that this is a wonderful show of wonderful work by a wonderful and hugely important artist.

Andrew Paul Wood

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.