Terrence Handscomb – 12 March, 2019

The best artists do what they like and don't care about the social, political or cultural consequences because the best art and the best shows will remake those consequences in their own image and likeness.

.

Reading ‘George Hubbard: The Hand that Rocked the Cradle’, an essay by Anna-Marie White and Robert Leonard in Reading Room: Politics in Denial, issue 08.18 (September, 2018).

The most interesting thing about the last issue of Reading Room, the (almost) annual art and culture journal published by Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, is that the discussion comes nowhere near instantiating the very thing it interrogates: cultural insurgency. In line with its editorial theme, many of its accomplished essays speak in confident academic accents about the efficacy and failings of cultural insurgency; about the politics of denial; about the artistic erasure of certainty; but they do so in a tight bourgeois intellectual context that is far from being any of those things.

In other words, Reading Room is a patron-funded, proudly refereed intellectual journal, with a critical mandate and an intellectual and editorial mood that effectively points this mandate away from itself and always to something else. Reading Room never becomes the things it mandates, because its judicious editorial governance prevents it.

The interesting thing here—and it is common throughout institutional culture—is that Reading Room/08.18 does so without itself being tainted by the social, political and intellectual precariousness its essays so keenly champion in others. There is always the editorial luxury of distance that institutional judiciousness bestows and Reading Room is comfortable in this conceit. I call this condition a state of representation, but I own nothing of its philosophical originality.

✽

The best part of White and Leonard’s essay tells of George Hubbard and his brilliant but exorcised 1993 exhibition proposal Brownie Points, which they exhume in ‘George Hubbard: The Hand that Rocked the Cradle’ (pp.30-53). They tell in well-researched detail of Hubbard’s callow but fatal conflict with the sclerotic intractability of Auckland City Art Gallery and the interdictive Māori interests that ACAG sought to honour.

White and Leonard’s discussion proffers insight into two often unacknowledged but opposing states: the intuition and cultural intelligence that can arise from unfettered artistic and curatorial freedom, and its institutional corralling and eventual occlusion. When the later speaks with the canonical voice of cultural authority, its messaging will be final and its intention is expected to remain unquestioned and untainted.

Hubbard’s engagement with the art world was unusual, and for this reason it is extremely interesting. White and Leonard’s case for Hubbard also tenders an insight into a cultural insurgency and a grasp of what could and should be, once the vestige of institutional authority has been ripped away and an open playing field is occupied by a free spirit. Ironically they do so in New Zealand’s most academically self-conscious art journal.

Hubbard came to New Zealand art without the pretext nor the authority of an art education. His was a renegade mutiny (one that was uncaring, unruly, ingenuous, and sometimes clumsy) against the juridical subtexts of both Pākehā and Māori cultural law and the bicultural posturing that both enabled.

He had a cunning disrespect for New Zealand’s cultural institutions. Like many street-level uprisings, his came with the clandestine shrewdness of the socially disenfranchised and their ancient cry for freedom. Sadly, it would be hubris that fed his expectation that the momentary free zone in which he could run wild was a wide-open space, and that his scamper would last forever. Hubbard’s dash lasted for all of the two seconds it took Māori and Pākehā cultural authorities to double-take and form a retaliatory interdict to be served immediately.

Hubbard’s failing was that he did not fully understand the complex manipulations and duplicities that abound when opposing states of representation compete for dominance in a public domain. This is something that is usually learned late after defeat and psychological injury have left deep wounds. Hubbard was like a deer in the headlights and the rest was roadkill.

✽

This is the parable of George Hubbard and his brilliant but exorcised 1993 Auckland exhibition proposal Brownie Points, which White and Leonard exhume. Their essay tells of Hubbard’s unfledged but fatal conflict with the institutional uncertainty of Auckland City Art Gallery with respect to the Māori cultural interests that it sought to honour.

In the end Hubbard ran away. His debilitating capitulation to ACAG and the subsequent devastation and paralysis of his spirit is a sad lesson for all of us. If you are thinking of killing Goliath, don’t wander onto the battlefield with no more than a slingshot. Come with guns!

‘George Hubbard’ is an openly critical historiographic narrative of this (once) young Māori curator who was active in the late 1980s and first half of the 1990s. Hubbard’s shows were embraced by many public art museums for their biracial inclusiveness; but equally rejected for exactly the same reason by a Māori hierarchy of cultural elites who were determined to control their own cultural narratives. Māori would tell their own story, and a culturally illiterate Hubbard would not be their voice.

In 1993 Hubbard pitched an exhibition to Auckland City Art Gallery with the hard-boiled, but hilariously provocative title Brownie Points (Bi-Culturalism and its Consequences). After protracted curatorial compromises and institutional bullying in which ACAG was determined to represent Māori in such a way that would not ruffle any feathers, the controversial but terminally refined show eventually opened in October 1995 with the heavily sanitised title Korurangi: New Maori Art.

The result was that Hubbard’s Korurangi experience killed his spirit. His encounter with a curatorial force that did not respect his loosely expressed need for freedom, ended with him being bullied into submission, a first for him—perhaps his borstal days were different.

Hubbard’s naïvely pitched Brownie Points with its sardonic title, pissed straight on the floor of New Zealand’s newly conceived but highly controlled bicultural lore, an authorised messaging that told the world how biculturalism would be understood in the public domain. But this sort of authority would not tolerate Hubbard’s street-level chortles. With Brownie Points Hubbard’s message was clear: it’s a mess on both sides of the bicultural divide and let’s not pretend otherwise.

One big problem for Hubbard was that his Māoriness was not Māori enough for the cultural elites who controlled the semiotics of representation on both sides of a burgeoning bicultural partnership. To some Māori elites, Hubbard’s representations were inauthentic.

White and Leonard quote Māori artist, writer and educator Professor Robert Jahnke (Ngāi Taharora, Te Whānau a Iritekura, Te Whānau a Rakairoa o Ngāti Porou):

“Hubbard does not speak for Maori people he merely speaks about them. … In order to speak for Maori one must earn the right. This right is not self-imposed but is decreed through genealogy, through acknowledgement or through deed. Even Pakeha may speak for Maori but it is a right conferred by Maori not Pakeha.” (p.37)

Jahnke’s comments followed Hubbard’s all-Māori Artspace Auckland show Choice (1990). Jahnke was a persistent Hubbard critic.

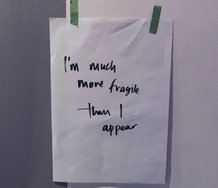

However Hubbard never attempted to ‘represent’ Māori per se. This was not his mandate and he resisted every expectation that he should do so. His own Māori identity, which not unlike his sexuality, was ambiguous and at times fraught with uncertainty and defiance. In his shows Hubbard wanted to represent Māori who were like him.

In the gap between Brownie Points and Korurangi Hubbard was pushed to rename the show and justify why he wanted to include some artists that could be deemed unworthy. This was a cynical move and by naming the politics of his new title Untitled: An Exhibition of Contemporary Maori Art expressed his simmering recalcitrance. White and Leonard quote Hubbard’s unashamedly autobiographical reasons for selecting artists:

“Some of the proposed artists in Untitled have grown up outside of the culture and have returned to find a place for themselves, some have been raised by Pakeha unaware that they have a Maori side to their family, some have Pakeha features and are not physically accepted as Maori, while others have a small percentage of Maori blood which is considered too insignificant to qualify them as Maori. Some of the Maori in Untitled simply do not fit in!“ (p.41).

ACAG legislated against Hubbard with a “Guest Curatorial Agreement,” which in effect meant he would sign away most of his power and all of his freedom. “The Gallery had final say” as White and Leonard put it. (p.40)

As I see it, Hubbard’s principle mandate was his will to freedom, but New Zealand’s bicultural identity politics was where he pointed his curatorial attention. His focus on New Zealand’s burgeoning biculturalism was a cunning exploration of its duplicitous and clumsy rawness. He did this extremely well, but not everyone liked it. Māori elites saw Hubbard’s dilution of what it meant to be a Māori artist a threat to their messaging. Hubbard seemed to lower their requirements of what was needed to represent contemporary Māori in Aotearoa New Zealand’s premier cultural milieu, and this was his eventual undoing.

Hubbard was a sort of Māori Dalit (ill-born “untouchable”—he was the illegitimate son of a young Māori woman who gave birth in a Salvation Army home. Soon after his birth he was spirited away into white middle-class adoption). His personal history drove his defiance and the odd psychological mix of alacrity and deep sarcasm that characterised everything he did. He could be very funny. Hubbard’s ideas for shows often entailed an experimental astuteness that usually involved hilariously sardonic dalliances and sarcastic tiles. For the art world insiders at ACAG this would be too much.

The cautious change of Pākehā attitudes towards biculturalism and the reinstatement of a proud Māori identity with its deep spiritual values, was no trivial matter. If Hubbard’s idolatrous ideas were to spill over into a ‘serious’ exhibition of Māori art, it would voice a bicultural narrative that would touch sensitive nerves on both sides of the cultural divide. Brownie Points‘ legislative reworking under the title Untitled and its final institutional transmogrification into Korurangi would prevent Hubbard’s semi-underground insurgency from burning the whole house down if left unchecked. In other words, Brownie Points‘ failure signalled to anyone who cared that Hubbard’s wild run would not change anything.

It didn’t help that at the time the ACAG curatorial team was trying to exorcise Hubbard from Brownie Points, Wellington City Art Gallery director Paula Savage commissioned him to organise the provocative ground-breaking exhibition Stop Making Sense. In this exhibition Hubbard teamed up Māori and Pākehā artists into often unlikely pairings with each being commissioned to make a work of art for the show. The resulting art was provocative to say the least. The show precipitated a cultural uneasiness for some and was seen as a hilarious intervention for others. Stop Making Sense was a localised Unbehagen in der Kultur, as Freud once put it, of the conflict between the desire for individuality and the expectation of compliance that society presumes. Without doubt Stop Making Sense was a shit-stirring challenge, but despite its unruly artist pairings the show made real a deep seated uneasiness and unholy Disquiet in the Culture.

Hubbard could be the manipulative stirrer that New Zealand art has always needed, and will always need. Anything that would piss-take the self-conscious earnestness and representational conceit that orders New Zealand art, was a Hubbard triumph. It also didn’t help that Stop Making Sense was a well-timed booted kick to ACAG’s sanitising of Brownie Points (Savage was a Hubbard fan) because it highlighted the institutional animosities and conflicts of egos between Wellington and Auckland that had been fuming away since Robert Leonard and National Art Gallery in Wellington took Headlands to Australia in 1992 without properly consulting Auckland. Auckland’s problem was that Headlands enabled the still infamous Walters iconoclasm, the malice of which has not yet abated in this part of the country—its memory still angers and its ghosts have not yet been properly exorcised.

There is a palpable gap between what is said and how it is said. Hubbard’s voice was a revolutionary cry of the renegade, which in New Zealand art meant it would inevitably have to pass through the dense filters of institutional containment, before it could be taken seriously. New Zealand art is mainly supported by private money from patrons. Couple this buying power with the institutional systems that filter the flow (it’s actually a trickle) of public funds, renegade voices like Hubbard’s will eventually be muted. Hubbard was the living breathing body of the outsider who naïvely believed his expectation of freedom would always be met. In this respect there is almost no distinction between artists and curators, who when they are both cut from the same cloth can do great things. Hubbard worked like artists do: it’s all about how it looks and how it feels at the moment of the making.

Hubbard was amongst the artists and curators who will always capture the public imagination by doing their own thing and appearing to get away with it. Always lurking in the shadows are the institutional mandates of insiders who have other interests to represent. Real freedom is rarely tolerated for too long unless it can be extrinsically represented and thereby contained.

The trouble with large self-conscious institutional ventures like Korurangi is that good ideas get the life sucked out of them by the bureaucratic need to justify everything, on paper and in committee. Cover your arse before you commit. Hubbard never curated this way and his process made him light enough to fly. But the Leviathan that Korurangi became meant the extra weight was too much and Hubbard crashed to earth and burned.

The institutional will to justify everything always leads to an excess of representation that gets mistaken for the real thing. With Korurangi Hubbard lost his real-thing-mojo.

When representation replaces pure presentation, what you end up with is a story and a state that is always in excess of that which is merely presented. Artists present, Hubbard presents, institutions represent.

To represent Māori and to articulate exactly what contemporary Māori art was (nobody knew back then but they all had their own ideas) and to represent biculturalism at a crucial time and get it right, was a tough call for any Aotearoa New Zealand cultural institution. ACAG came away from Korurangi completely frazzled. They hid their collateral damage but it was their own fault. They should have let Hubbard run with it and swept away the pieces of fake history that that would have fluttered to earth after the explosion. They could have waited out the time it took for the inevitable fragments of cultural truth to emerge from burnt earth, and then owned them and thereby demonstrate to the world that they were a kick-arse concern. Instead they did what they always do: they owned a curatorial process that was flawed from the beginning. You can’t orchestrate a revolution then call it responsible custodianship. Less so when public funding is involved.

Rather than contain Hubbard, ACAG should have let him have his head and they would have probably ended up with the most honest show they have ever done. The bottom line is that the best contemporary ‘Māori art’ will have to flourish in an art world in which both Māori and Pākehā play only a small part. This has a profound bearing upon what it means for Māori to make art in a brave new world. Michael Parekowhai’s fabled piano, He Kōrero Pūrākau mō te Awanui o te Motu: Story of a New Zealand River (2011)—the one that went to Venice, the one that Te Papa paid a scandalous $1.5M for—was carved by a Pākehā artisan. Should this truth be celebrated or concealed?

The best artists do what they like and don’t care about the social, political or cultural consequences because the best art and the best shows will remake those consequences in their own image and likeness.

Real breakthroughs in art are chaotic, and when they occur no one knows what the hell is going on. Moreover, if an unmediated and unrepresentable state of pure presentation were to appear in art, its force would deconstruct any representational excess that tried to make sense of it. Scandal would be the only thing that could patch over the semiotic wounds in the sovereign discourse. No one could write about that sort of art because they would have no way to represent it. Apart from professional vanity, why would anyone want to? Let history make sense of it, because new representations will always appear and new visual vocabularies will replace old ones and all will be good in the world.

✽

Early on, Hubbard’s arts coming of age percolated through his social engagement with the visually loud but socially snooty apprentice caste otherwise known as “the hairdressers.” These were the colourful representatives of an uneducated socio-economic casting that suited Hubbard’s ideas of origins.

This was Wellington in the late 1980s when residual punk and a newer street-level couture informed sartorial expression; which when coupled with big outrageously coiffured hair, became the standard uniform of the cool people. This was the short-lived age of the hairdressers but their parties were the places where they met the commoners. Educated cool straight kids and marginal art-farts like Hubbard would be tolerated if their hair was good and they met the dress code. Everyone went to select gay bars (there was only one, the tiny Bamboo Bar in the Oaks complex) and clubs where the hilarious sexual theatricality of leather caps, chaps and jockstraps was new.

These places were the most fun because they were places where social marginality was celebrated and where Hubbard felt accepted. ‘Queer’ signified pride and this newly re-appropriated locution was quickly injected into quotidian vocabularies. This was a hubristic time of hard-core sexual expression hastened by a desperate intensity that would portend the AIDS cull that quickly put a stop to everything.

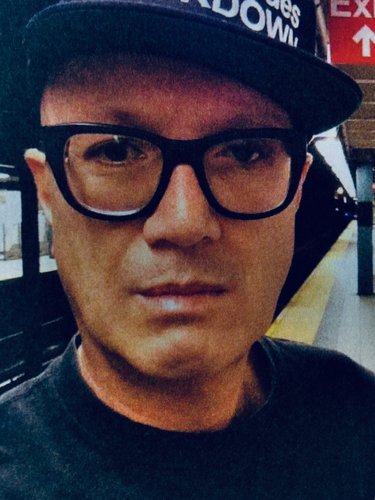

I first saw Hubbard at such a party. He was dressed like a street-level-black-momma-Bess-without-Porgy, but with punky details and a lot of makeup. He looked straight through me, but we all did that.

Eventually we formed an arts alliance that would last until he did a runner. I could be a tough date but George didn’t care because he could be one too. His alacrity could cut through shit. I suspect we gelled because we both didn’t give a fuck about what anyone thought, but we actually did and kept it quiet.

It’s been ages since Brownie Points and Korurangi and we haven’t seen much from Hubbard since. Maybe he will have a second run. Who knows? But if all this reads like an obituary it is because it is highly unlikely that Jedi George could ever recall the force.

Terrence Handscomb

Recent Comments

Ralph Paine

VI. In my view we shouldn’t consider George a victim (unless we're all victims!), and nor should we be resentful ...

Ralph Paine

V. There’s a focus in Anna-Marie and Robert’s essay on George as auteur curator. I kinda get that——fall too far ...

Ralph Paine

IV. It’s important to note here that Choice was an Artspace exhibition, as was Cross-Pollination. So it turns out that ...

Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

This Discussion has 6 comments.

Comment

Ralph Paine, 5:13 p.m. 13 March, 2019 #

I.

Thanks Terrence!

Despite George NOT being dead, not even sort of—you’ll spook yrself with that kinda talk—it was nice waking up this morning to such an inspiring hit of counter-history: I agree 100% with yr assessment of Reading Room... Never down in the fray, always pretending to sit above it. Yeah, so more like Reaping Room, the deadly drone of Official History. I like the way you conceive our historical problem: history is only the NEGATIVE condition of our becoming (becoming-maori, becoming-woman, becoming-queer, becoming-animal, becoming-imperceptible) so how to gear-up our writing machines appropriately?

Yes, it’s almost impossible getting a fix on George's Aotearoa based art-life—like you say, in those days he was rapidly shape-shifting his way through many a different milieu, often secretly. He and I were friends, in a provisional kinda way—but what other kinda friendship is there? Viva the Ad Hoc Adventure! And anyhows, in the art scene we're speaking of here everybody was a good friend, even those who turned out to be enemies (not that that’s what happened with me & George). George was extremely cool, in both senses of the word, and thus somewhat of a well styled puzzle: mercurial, enigmatic, yet always with a very fixed and precise eye, attitude, dress code: he looked good and was good at looking. I considered him an anomalous one, an Original (in Deleuze’s sense), operating from the fractal edge, even when capturing/captured-by the centre (e.g. Korurangi ), often silently disappearing into the dark of the night only to reappear suddenly days, weeks, months later in galleries, offices, on doorsteps, on the street, always carrying some new and interesting artwork, objet, music tape, flyer, catalogue....

Ralph Paine, 5:14 p.m. 13 March, 2019 #

II.

We met in Wellington, 1988. George had written asking if I'd like to have a show at Cupboard Space, his little shop front gallery in I-can't-remember-what Street. Yeah, he was a gallerist before getting into curating, but I don’t think he spent much time trying to figure out the difference. I'd never heard of George, and was unsure how he'd heard of me. The previous year I'd exhibited a series of paintings named The Incest Taboo at (what was then) Artspace's George Fraser Gallery in Albert Park, so perhaps someone had mentioned something positive to him about that. Or maybe he'd seen the Wystan Curnow curated exhibition Sex and Sign. In any case, I wrote George back: “Yeah, I'd love to come down and exhibit a few of these paintings.” He was chill with that, easy, so sometime during the winter a friend drove me to Wellington with 6 or 7 of The Incest Taboo stacked in the back of her car. George and I hung the show together the same day as the opening. We immediately clicked, no hassles, lots of Marlboro Lights. At some point George mentioned he had some $$$ for my expenses: "Forget it" I said, "Let's just buy some Moet for the opening". After that, we totally got each other. I remember Terrence, wearing full tennis whites, calling by during the arvo for a brief bitchy chat... Yeah, Wellington.

Towards the end of his Auckland period George used to hang small shows in a bistro on High St (can't remember its name) and perhaps his very last hang there was a group of hand-painted ceramic plates that Gavin Chilcott and I had made together back in 1995. Funny, I haven’t seen George since, and nor did we get the plates back—they disappeared into the night never to be seen again, although turns out one of them might be in Simon Manchester's collection in Wellington, if it survived the earthquake that is. OK, so George had a way of circulating things on somewhat divergent paths. Everything was intended to travel along some magical tangent, and to keep travelling: one day the return might happen, but always in a somewhat transversal and incalculable manner. Call this an informal economy, an economy of the gift (hau), an economy of intimate expenditure à la Bataille... Whatever descriptor we may wanna use, it's an economy where friendship networks are where one always begins and ends. Nomad hospitality is another appropriate term. Not that in the real this is a conflict-free zone, as these kinda networks (like all networks) require certain forms of resistance, switching, competitiveness (witness potlatches), shifting alliances (contra contracts), noise (e.g. the daily friction caused by the requirement of finding food, clothing, shelter). Perhaps then the word utu (in all its complex nuances) is better suited when trying to describe how George liked to play it in the realm of goods and services.

Ralph Paine, 5:16 p.m. 13 March, 2019 #

III.

But rather than using revolutionary and avant gardist analogies, or producer, independent curator, cultural operative models, these days I'm inclined to view George through a Fourierist lens, i.e. through a utopian-type lens manufactured in the Happy Workshop of the Passions. If La Rochefoucauld understood our virtues as mostly vices in disguise, Fourier flipped this on its head, reconfiguring our vices as mostly virtues in disguise, and thus expressing in his writing a fresh way of transforming society premised on an early kinda Libidinal Economy. In this sense I consider George's outsider, bad-boy persona as one fine tuned in the last instance to the task of anti-repressive and anti-representational commoning... How best to live in harmony with our "natural" instincts and inclinations? How best to love THIS world? How best to live and work and die together in this place, on the streets of this city, any-city-whatever? George exuded a wickedly funny, low theory vibe, a ghetto-style sensibility and natural caution cross-pollinated with enthusiasms for Tino Rangatiratanga and Semiotext(e), Panbiogeography and anti nuclear activism, etc. etc. Yet at the same time he enjoyed very dry and hiply ironic conversation, fine food, wine, and drugs (yes, George was an Epicurean in the best sense of the word), hanging with rap artists, taggers, gallerists, pitching to museum directors, collecting art & objets.

Fourier conjured up his World-System using various mixed groups of passions, all "distributed" and reshuffled via his three Series Passions: i.e. the Butterfly Passion, the Cabalist Passion, and the Composite Passion. The Butterfly Passion is a desire for regular change and variation, a desire induced by the fact that after two hours or so on task we become bored and thus our enthusiasm turns to negativity or indifference. The Cabalist Passion is a desire for intrigue, deliberate plotting, and partisan scheming. And the Composite Passion is a desire for complementarity, for the modulating and blending of different singular tastes and desires to create even more productive and enjoyable experiences. Without him ever talking like this, I believe George more often than not took heart (and no doubt still does!) from the pleasures and possibilities held by all three of Fourier's Series Passions: change it up, plot and scheme, mix it up.

Ralph Paine, 5:18 p.m. 13 March, 2019 #

IV.

It’s important to note here that Choice was an Artspace exhibition, as was Cross-Pollination. So it turns out that there once was an institution where George’s ways were instantly recognised and appreciated as being innovative and exciting. Strange then that Anna-Marie, who these days is working with George on various projects, chose to co-author the essay with Robert. I’m way over it now, but for a while there I retained very strong negative views about Robert’s restructuring of Artspace, his agreed-to-by-the-then-board demands that the constitution be rewritten so as to remove the role of the programming committee and hence that all curatorial decision making power, etc. be given to the director. In my view George's story is a very good example of exactly how well the old ways worked! It's interesting to read in the records of the time of Robert et al.’s Artspace restructuring a bemoaning and critique of curating-by-committee (also see: Anthony Byrt's Leonard-supervised Masters thesis). But what is curating-by-committee, what does a curatorial committee do? And further: are there different examples, different ways of curating-by-committee?

Ralph Paine, 5:20 p.m. 13 March, 2019 #

V.

There’s a focus in Anna-Marie and Robert’s essay on George as auteur curator. I kinda get that——fall too far down the personal is political rabbit hole and there'd be no coming back—but then everything hinges on our understanding of what curating is, of what it is that curators do. But in my view we should never have been talking Auteur vs. Committee. Back in the early 90s the Artspace programming committee was always keen to include different kinds of curating—mix it up!—including auteur curatorship. Clearly Choice and Cross Pollination are good examples, but Derek Cherrie's Billboard Project and Bridget Sutherland & Stephen Zepke's Light Sensitive are others—the later being collaborative-auteur! At other times the committee itself curated e.g. Media-Trix, and so on. Curating is always a collective enterprise, a labour-tech nexus with amazing potential. In this sense, why no mention of George operating in a late-analog/early-digital time frame? Where’s the materiality of (art)history?

Here's another reason why it's gonna be difficult getting a fix on George's Aotearoa based art-life: the art scene (the labouring and the tech that he was once part of) has been utterly transformed, restructured, captured, re-coded, over patronised, professionalised, given false historical spins by new elites, new cultural captains, etc. And here I'd include the Maori world. You’re right Terrence, we’ve gotta remember that George was operating pre-official biculturalism, pre-Foreshore & Seabed, pre-Maori Party, pre-corporatisation of iwi, pre-liberal education's embrace of identity politics and post-colonial studies, etc. etc.

So yeah, it's worth viewing contemporary art as something folded deep inside that somewhat more amorphous beast called global culture. These days I like Paul Gilroy's take on culture, but Nietzsche's definition of culture as both "selection and training" might be useful: sure, curators choose, but they also train. George was happy when choosing, but resisted the training side, the pedagogy.... Perhaps this explains some aspects of Cross-Pollination's good chaos.... Choosing a group of artists and then pairing them up is one thing, but helping facilitate and nurture the working relation is something artists are quite capable of dealing with themselves. George liked to set up situations and then sit back and watch what happened. At times I got annoyed with this, but I get it now.

Ralph Paine, 5:21 p.m. 13 March, 2019 #

VI.

In my view we shouldn’t consider George a victim (unless we're all victims!), and nor should we be resentful about the tattered remnants of his so-called “career”. Thing is, he did everything within his power NOT to have a career, especially not a "respectable" one. Which just might mean that he desired—despite the then encroaching fog and shadow—to live what Agamben calls a “form-of-life”? This, I believe, is what some of us briefly shared with George back then and doubtless still do: an almost unspoken kaupapa or ethos wherein careers and institutions are somewhat beside the point, and what previously I called commoning is. This is why I like using the word maori with a small 'm': people, common, fresh....

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.