Scott Hamilton – 14 January, 2020

The case contained the life work of Angus MacLise, who had been a founding member of two of the most innovative musical outfits of the 1960s, the Velvet Underground and La Monte Young's Theatre of Eternal Music. MacLise was the Velvets' percussionist, but quit the group after learning Lou Reed had agreed to play a gig in a nightclub. For MacLise, who liked to hit his drums for hours on end, the notion of having to end a concert at a fixed time was anathema.

EyeContact Essay #36

In the summer of 1979 a white man died in the charity ward of a Kathmandhu hospital. His emaciated body was carried to the Bagmati River, placed on a low platform, and burned. The man had left behind a suitcase, which was given to a friend, a fellow American. The friend stored the case in his New York basement, and forgot about it.

In 2008 an historian named Johan Kugelberg opened the suitcase. It was filled with reel to reel audio tapes, paintings, drawings, manuscripts and photographs. As he worked through the trove, Kugelberg encountered traces of some of the twentieth century’s most famous avant-garde artists, and musicians. He recognised John Cale, Lou Reed, La Monte Young, Terry Riley, George Brecht.

The case contained the life work of Angus MacLise, who had been a founding member of two of the most innovative musical outfits of the 1960s, the Velvet Underground and La Monte Young’s Theatre of Eternal Music. MacLise was the Velvets’ percussionist, but quit the group after learning Lou Reed had agreed to play a gig in a nightclub. For MacLise, who liked to hit his drums for hours on end, the notion of having to end a concert at a fixed time was anathema. MacLise had also worked with the Fluxus art movement. He had published books of poetry on three continents. He had studied magic with disciples of Aleister Crowley. He had filled notebooks with paintings and collages.

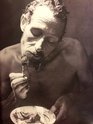

In the 1970s MacLise settled in Nepal, attracted by the country’s community of exiled Tibetan shamans and by its cheap opiates. He and his wife Hetty had a son, Ossian, who was soon declared a tulku, or reincarnated holy man, by Buddhist authorities, and taken to live in a monastery. By the time he entered hospital in Kathmandu, Angus MacLise was suffering from tuberculosis and malnutrition.

The suitcase discovered by Johan Kugelberg supplied much of the material for Dreamweapon, an exhibition held at New York’s Boo-Hooray Gallery in 2011. The exhibition and its catalogue book prompted some belated interest in MacLise’s oeuvre. The New York Times headlined its review of the show ‘The Velvet Unknown, Now Emerging’; Dazed Digital called MacLise’s suitcase ‘an incredible relic’.

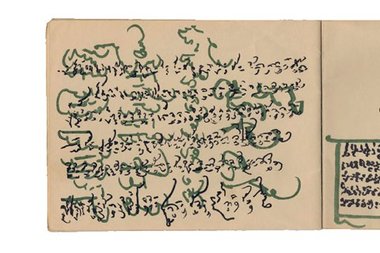

The exhibits at Dreamweapon included sheets of paper covered in a fluid, inscrutable handwriting. Using black ink and brushes, MacLise had sent his cursive lines up, down, and across pages. The edges of MacLise’s characters were clean and curved, like scimitars; they recalled the Arabic script. Occasionally a strange figure, some bulging quadruped or sinister anthropod, half-familiar from an Egyptian hieroglyph, seemed to creep from the lattices of ink.

But MacLise was not writing in Arabic, or in Egyptian. Some guests of the Boo Hooray gallery were frustrated, as they attempted to decode the pages of calligraphy. With its bold forms and its detail, MacLise’s handwriting seem to visitors like it must teem with meaning. But the more they looked, the further sense seemed to recede from the strange pages.

Angus MacLise was neither the first artist nor the first adept of the occult to create his own alphabet. As a child the Polish sculptor Stanlislaw Szukalski concocted a baroque script, which he insisted on using at school, and continued to employ for the rest of his life. MacLise would have been familiar with, if not fluent in, Enochian, the language that the seventeenth century scientist and magus John Dee claimed to have learned from angels. Dee and Aleister Crowley and other practitioners of ‘Enochian magic’ wrote spells in a peculiar script, a series of square, bulky shapes.

But the Enochian alphabet corresponds to a series of sounds, and the Enochian language translates easily - far too easily, some sceptics have said - into English. MacLise’s script, by contrast, offers us no obvious correspondences with vowels and phonemes and phrases. It is untranslatable.

MacLise’s calligraphy reminds me of the texts that the people of Rapa Nui carved on fragments of driftwood, on paddles, on cave walls, and on banana skins. By the time the first interested European visitor to Rapa Nui had encountered a carved tablet in 1865, most of the island’s people had been stolen by slavers or killed by smallpox. Survivors knew that the script was called rongorongo, but did not know, or would not share, its meanings.

Rongorongo has obsessed a series of Western scholars. Again and again, linguists and ethnographers and cryptographers have announced the ‘cracking’ of Rapa Nui’s code; again and again, their solutions have been ridiculed. The Soviet ethnographer Irina Feodorova offered this version of the seventh line of the rongorongo tablet known as ‘Text C’:

a root, a root, a root, a root, a root [that is, a lot of roots], a tuber, he took, he cut a potato tuber, he dug up yam shoots, a yam tuber, the potato tuber, a tuber…

Feodorova admitted that this passage was ‘worthy of a maniac’. But did the mania belong to the scribe who carved Text C, or to its would-be translator?

I have been thinking about Angus MacLise and the language of angels and the rongorongo of Rapa Nui because I recently saw a painting by Allen Maddox in Whangarei. The town’s gallery is showing off a series of artworks made in 1980s New Zealand, and Maddox’s Untitled hangs opposite one of his old comrade Philip Clairmont’s blazing window-paintings.

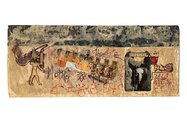

MacLise was forty-one when he died; Maddox lived to fifty-one. MacLise was addicted to heroin; Maddox needed scotch, speed, LSD, and the medication that controlled his schizophrenia. Like MacLise, Maddox was a deliberately enigmatic artist. Over a quarter of a century, he covered hundreds of canvases in crosses. Sometimes he was content with a single cross; sometimes he stacked dozens of them up, into structures that threatened to drown or dissolve in brushstrokes of violent colour.

Like Clairmont and his other great ally Tony Fomison, Maddox was often called an Expressionist. But his paintings lacked the pictorial content — the striding skeletons, the hooded hanging judges, the burning gardens — that guided interpreters of Clairmont and Fomison. Maddox’s fierce use of paint and colour hinted at an urge, and perhaps a need, to discharge some idea or emotion or memory, but the simplicity of his paintings’ recurrent gesture thwarted this urge. The result was, and is, a sense of pent-up, angry energy, of ghosts trapped and raging.

Maddox grew up in working class Liverpool, and emigrated to Napier in his mid-teens. He was proud of his proletarian lineage, unashamed of his mental illness, and estranged from the metropoles of the art world, with their gossipy curators and exquisitely refined critics. Like psychiatric wards, art galleries were traps.

For Maddox, the cross seems to have begun as a gesture of rage, and a means of obliteration. As a young man, he apparently used it to deface images he had been working on, but had become unhappy with.

But Maddox fell in love with the cross. Perhaps, as Alice Hutchison has suggested, he was trapped by the shape. The crosses in Maddox’s paintings resemble the marks that his illiterate ancestors made on census forms, court papers, police registers; they remind us of lives that were inaccessible to literature, art, intellectual elites. But Maddox’s cross also indicates a refusal, a withholding of information, a keeping of secrets.

Perhaps, in the twenty-first century, the recalcitrant art of Allen Maddox and Angus MacLise is acquiring a peculiar sort of meaning. The late Mark Fisher argued that, in the era of postmodernism and stagnant capitalism, culture has become ‘a sort of networked solipsism’. On social media, for example, we boast, confess and quarrel with each other, in what ought to be an orgy of self-expression. And yet the more we express ourselves, the more hackneyed, the more unoriginal we seem. Our thoughts have been thought before, our feelings felt by strangers.

In our era, Fisher said, we need to see the ‘value of disappearance from the screens that eagerly seek our image’. It is necessary, he argued, ‘to withdraw in order to find better ways to connect’. Perhaps we should feel grateful for the recalcitrance of Angus MacLise and Allen Maddox, and excited rather frustrated by the evasiveness of rongorongo.

Scott Hamilton

Recent Comments

Wolfgang Sperlich

Interesting article. Secret languages in Oceania abound. Nevertheless, Aotearoa has its very own code-cracker in Steven Fischer and his 1998 ...

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 1 comment.

Comment

Wolfgang Sperlich, 9:13 p.m. 23 January, 2020 #

Interesting article. Secret languages in Oceania abound. Nevertheless, Aotearoa has its very own code-cracker in Steven Fischer and his 1998 Rongorongo: The Easter Island Script: History, Traditions, Text (Oxford Studies in Anthropological Linguistics). I was in Kathmandu in the 1970s twice and might have come across Angus MacLise. As a linguist one can only refer to Chomsky who maintains that all human languages, secret or public, are products of a biological brain, hence ultimately decipherable (not necessarily by academics who these days have a tendency to do research for the corporate sector). That the language of social media is restricted to something called Twitter must be a real worry: the language of twits. QED.

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.