Peter Dornauf – 27 August, 2020

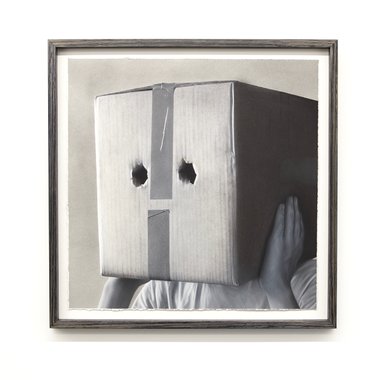

There is also a nice frisson between the faultless surface and finish of the work and the low rent materials used in the props. This somehow lends credence to the ‘reality' of what we are looking at. Then the images themselves confront the question of perception itself. McAlpine presents his figures wearing various devices over their heads and eyes — boxes with the ubiquitous eyeholes punches in, bifocals (empty toilet rolls) heavily and roughly taped to the face; even a virtual reality headset.

Oh, consummate and real reality, where really art thou?

It was Plato who first alerted us to the epistemological conundrum with his cave allegory. Then Kant put his own spin on it, placing the phenomenon at odds with the unknowable noumenon. Today however, we are more concerned with the various screens and filters that technology throws up that separate us from or manipulate the forms of our perception/reception of reality.

Contemporary American politics has thrown into sharper relief the tricky question of distinguishing fact from fiction, truth from the counterfeit, while Baudrillard added to the riddle with his notion of the loss of the ‘real’. This is where artist Harry McAlpine comes in. He engages with the complete network of this theory and sets about messing with our minds by employing a method of representation in his work that, well, blows our minds.

First he takes a black and white photograph of his artificially constructed subjects. Then he meticulously copies the photographic image onto cotton (rag) paper using charcoal, rendering the duplicate close to the original.

We are at three degrees of separation here, the viewer completely fooled by the hyperreality, suckered in by the simulation where every fastidiously crafted strand of hair or tiny crease in the cardboard is made to look immaculately photographed. Replica and original defy distinction.

There is also a nice frisson between the faultless surface and finish of the work and the low rent materials used in the props — cardboard boxes, makeshift binoculars made out of cardboard tubes. This somehow lends credence to the ‘reality’ of what we are looking at. Then the images themselves confront the question of perception itself. McAlpine presents his figures wearing various devices over their heads and eyes — boxes with the ubiquitous eyeholes punches in, bifocals (empty toilet rolls) heavily and roughly taped to the face; even a virtual reality headset.

What is being toyed with is that we, in the digital age, are as it were, locked inside the territory that was more literally explored in the film, The Matrix. We are all Neo types, trying to negotiate our way inside the dark labyrinth of constructed reality pitted against the real, ‘forced’ to wear a visor or mask through which we peer at the world, unable to tell shadow from authentic substance.

The idea of the mask is an old trope used in art that reaches back to James Ensor, Emile Nolde, Picasso, Magritte (The Lovers), Louise Bourgeois (Woman House), and more recently, Cindy Sherman and Ndiritu Grace (The Nightingale). But McAlpine, building on that and others who have made the TV head images all-pervasive, has contemporised the stratagem. We all wear boxes on our heads, looking out at a world riddled with shape shifting platforms that belong to the mass/social media, acting as screens that interpret, distort, deform, filter, censor, manipulate, enflame, edit and colour reality.

The title, Frankenstein, given to two of the works in the show, plays on the notion that science/technology has created yet other monsters who stalk the corridors of the world, heads bent so long into their devices that they take on the behaviour of automatons. These new “hideous sapient creatures”, heads filled not with straw, but fake news, conspiracy theories, inflated rhetoric, alarmist narratives, false hopes, fetishised suspicions, cultures of fear, the tyranny of the current, the madness of the melodramatic, dread of the future, silly panics and the socialisation of fragility, are versions of the new postmodern Prometheus.

Siloed is an engaging exhibition that has instant appeal, where certain key works strike the viewer with abrupt and telling force, and where the photorealist artistry is a jaw-dropping delight.

Peter Dornauf

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.