John Hurrell – 23 December, 2022

The items in this survey that interest me are those with exterior and interior architectural content. (No people.) I really like them. Early on we see buildings in contextualising harbour landscapes that wave to Binney (and occasionally Angus), and at the end we see the décor of uninhabited rooms containing (usually) wearable articles and contemplative household objects, resting on ornate furniture. The show finishes at a peak, for she has a flair for abstraction, especially when her pictorialism is flattened.

Auckland

Robin White

Te Whanaketanga / Something is Happening Here

Curated by Sarah Farrar and Nina Tonga

22 October 2022 - 30 January 2023

This large informative survey of Robin White‘s art practice (much of it collaborative) includes over seventy items made between 1970 and 2021: mainly paintings, prints, drawings, photographs, and a bound workbook. (Some super-enormous hiapo works—too big to be contained on any single gallery wall—might perhaps be called sculpture.) The exhibition is the result of a partnership between Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki and Te Papa.

Although its title partially comes from mid-sixties Bob Dylan, the show focusses on Aotearoa, a wider Pacific sensibility, and the landscape, people, architecture, and religious philosophies that White loves.

Some artists are indifferent to their surroundings, focussing on making work that has no connection with their immediate location. White is not one of those. Her biography can be tracked by sequencing an art production that is linked to her passion for getting involved with different places and communities, tied to a series of various homes and travels. Therefore works can be connected to locations like Bottle Creek, Portobello, Tarawa (in Kiribati), and now Masterton.

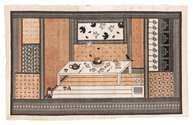

The items in this survey that interest me are those with exterior and interior architectural content. (No people.) Early on we see buildings in contextualising harbour landscapes that wave to Binney (and occasionally Angus), and at the end we see the décor of uninhabited rooms containing (usually) wearable articles and contemplative household objects, resting on ornate furniture, inlaid tables or tiled floor. The show finishes at a peak, for she has a flair for abstraction and decoration, especially when her pictorialism is flattened.

The items in this survey that don’t interest me are the lugubrious (if not maudlin) portraits, or clumsily modelled figures and faces like in Aio Ngaira—this is us. Instead of her painting, I’d rather look at her more successful woodblock and linocut prints for nuanced plasticity when rendering human physiognomy—where bone structure is alluded to better. In spite of her long interest in narrative and place I prefer her more formal compositions. They work really well where geometry is applied to receding or picture-planed space.

White‘s woven images on dyed pandanus leaves are fascinating precursors to the much larger hiapo hangings that have intricate, patterned stencilling, feathery texture rubbings, and elegant Japanese / Persian space. Complexly made, the earlier depicted food items such as a loaf of bread or can of fish are like simplified small buildings, seen from the front, that we have privileged intimate access to.

Their wit lies in combining Pop Art subject-matter (seen in illusory space) with the (unbiblical) dust of one’s feet (countered by hospitable dry matting on the floor: one interpretation); or with sharing prepared meals or hot drinks (offset by absorbent table mats: another reading). Two functions meet as one—representations of consumerist brands and household practicalities for when enjoying them. Image, pragmatic and social requirements are inseparable.

In my view, the most intriguing work in the show is Summer Grass, 2001, a collaboration with Keiko Iimura. A long work depicting a dry paddock and picnic tables, painted on wallpaper, it seems like a very skilled blending of Bill Sutton’s South Canterbury landscapes, Michael Hight’s cylindrical hay bales, the structure of McCahon’s On Building Bridges, and Bill Hammond’s bird paintings. Highly evocative with a lot of air, it is super mysterious, very ambitious, and the best by far of the outdoor landscapes.

As I’ve said, the show ends with a bunch of wonderful interiors that have a gentle musical quality, not only through rhythmic pattern, but also through the repeated use of depicted wall edges and large expansive rectangular planes that tonally affect the mood. There is an unusual emotional intensity that is hard to put your finger on. A calming stasis. White has talked about her love of Matisse. A hint of the geometry of Seurat also perhaps?

In an adjacent gallery video the artist talks about the specific choices of depicted object, how they have intended meanings, but I’m not sure that matters for the viewer, for they participate in a more porous interpretation. Their experience is bodily, not a list of rattled off creative intentions—more an emotional coalescing of the senses—though they might recognise the symbols.

One other work I admire, because of its extraordinary impenetrability and ambiguity, is the very large Moana Loloto / The Crimson Sea, 2014, a huge, black, highly textured, tapa rectangle, with undecipherable symbols buried underneath it. Made by White with Tongan artists, Ruha Fifita and Ebonie Fifita, it is intended to declare that the word and love of God has no limits, like the fathomless ocean, an incredibly positive thing. One might think though that it references Revelation or Exodus, and alludes to a bloody Armageddon, or a global climate disaster causing the calamitous demise of our planet. The title sounds gory, but the red refers to the colour of the iron pigment under the black (of candlenut soot).

That apparent turbulent pessimism, with a grim Old Testament ethos, is not the case. The final rooms that come after it introduce a calm serenity, and one of the exhibited titles states Soon, the tide will turn, a brilliant offering of hope, as if anticipating and counteracting the contrary interpretation. An optimism in the resourcefulness of our species in its ability to survive, and faith in the power of Love—and Art itself.

John Hurrell

Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.