Norman Franke – 4 December, 2023

Early 19th century Gothic Art's topics are often located at the interface of fear and desire, and sometimes referred to as 'Angstlust' in psychoanalysis. Early forms of this paradoxical artistic fascination with breaking social and sexual taboos were not only employed in an analytical manner and as a critique of Enlightenment discourses, but also as a form of entertainment. Artists like Henry Fuseli (1741-1825) for example, who emigrated from Switzerland to England and became a best selling painter in London, examined the narratives and images of the unconscious in their pictures to great public acclaim.

35 Collection works from 24 artists (Francisco de Goya y Lucientes, Andrew McLeod, Henry Fuseli, Tony Fomison, Megan Jenkinson, Henry Armstead, Ronnie van Hout, Tony de Lautour, Edmond Sullivan, David Wilkie, Barry Cleavin, Salvator Rosa, John Soane, John Mortimer, Etienne Aubry, Dane Mitchell, Peter Siddell, Alexander Runciman, Felix Kelly, Giovanni Battista Piranesi, Joachim Koester, unknown, Austin Spare, and W. D. Hammond.

Gothic Returns: Fuseli to Fomison

Curated by Sophie Matthiesson & Kenneth Brummel

2 September 2023 - 31 August 2025

This exhibition, Gothic Returns: Fuseli to Fomison, which runs until August 2025 on the narrow mezzanine corridor gallery of the Auckland Art Gallery, presents a condensed overview of an artistic genre that began in Europe in the 18th century, and spread from there to various other regions of the globe—including New Zealand where it is is still being adopted, modified and critiqued by contemporary artists.

“Incorporating all things unsettling, mysterious, sombre and downright scary,”(1) as the exhibition website describes them, such themes and styles of ‘Dark Romanticism’ have accompanied modernity since its beginning; but this view is now viewed cum grano salis (with a grain of salt). One can say that many of the modern fears, frustrations and repressions that the pioneer psychoanalyst Siegmund Freud described in his theories in the early 20th century were anticipated, and found early artistic expressions in Dark Romanticism. Gothic Art though, is often synonymously used for Dark Romanticism, and is both an art historical double entendre and a double misnomer. It alludes to the Romantics’ renewed interest in the Middle Ages, particular medieval or Gothic ambiences, but is itself early modern rather than medieval. The medieval Gothic style, however, has nothing to do with the eponymous Germanic tribe of the Goths that clashed with the Romans in late antiquity and whose name was expropriated to refer to a non-classic, organic and allegedly even ‘barbaric’ style.

Early 19th century Gothic Art’s topics are often located at the interface of fear and desire, and sometimes referred to as ‘Angstlust’ in psychoanalysis. Early forms of this paradoxical artistic fascination with breaking social and sexual taboos were not only employed in an analytic manner and as a critique of Enlightenment discourses, but also as a form of entertainment. Artists like Henry Fuseli (1741-1825) for example, who emigrated from Switzerland to England and became a best selling painter in London, examined the narratives and images of the unconscious in their pictures to great public acclaim.

Fuseli’s grotesque, often nightmarish images, such as that of an incubus (a demon that has sexual intercourse with a human in their dreams) sitting on a sleeping woman’s chest while a delirious horse in the background witnesses the scene, have become iconic images of early modernity. Preceding Freud by more than a hundred years, Fuseli submitted: “one of the most unexplored regions of art are dreams”.(2) It was the artist’s carefully scrutinised exploration of dreams rather than an overconsumption of raw pork and opium (as some of his early critics had speculated) that produced Fuseli’s spellbinding imagery of horror and lust.

In his Fuseli Tribute I (2009), the Aotearoa artist Andrew McLeod unfolds a photographic tableau of Fuseli’s erotic art that resembles an apartment building, each flat housing a screen-like allusion to Fuseli’s work. Powered by an electricity pole on the left side of the collage, a variety of Fuseli’s fantasies are spread across the different floors of the imaginary building. This slightly surrealist and tongue-in-cheek arrangement may well be meant as a reminder to what extent Fuseli’s works have become part of the erotic imagery of the modern collective psyche. Through modern media and advertisement Fuseli’s images have reached main-stream audiences.

One of Fuseli’s oil sketches depicting the three witches from Shakespeare’s Macbeth is on display at the Auckland exhibition. Against a dark background, seemingly out of nowhere, the pale prophets of Shakespeare’s Macbeth take on androgenic features. With their fanatically distorted faces and their elongated hands and fingers, the three witches (also known as the ‘Wayward Sisters’ or ‘Weird Sisters’) point towards the demise of the the king and his realm, looming in a futuristic dark space outside the picture. Hardly visible at first glance, above the wildly gesticulating doomssayers hovers a death-head moth. Often understood as the personification of destructing forces in the human psyche and in human civilisation, the interpretation of Macbeth‘s three witches has occupied psychologists and philosophers alike.

In Civilisation and its Discontent (1930) Freud argued that the very mechanisms that guarantee social cohesion, civilisation and peace in modern societies, such as the sublimation of urges and the subordination of individuals to rule-based political structures, also contribute to boredom, frustration and discontent as they disregard the spontaneous and ecstatic dimensions of the human psyche. Combined with narcissism, entitlement and greed, the politics of dictators and self-styled saviours claim to overcome the ennui of the established social order, only to reproduce it or to make it worse in the end. Dark Gothic art became prominent and flourished in the days of the early Industrial Revolution, the spread of global Capitalism—but also the revolutions of 1789 and 1848 and the rise of populist autocrats such as Napoleon Bonaparte.

The darkly mischievous adage of the Shakespearean witches: “Fair is foul, and foul is fair/ Hover through the fog and filthy air”(3) intersects with William Blake’s later attempts to redefine Puritan sexual politics in the wake of Milton. The anarchic and liberating potentials of sexuality began to fascinate the first generation of English and German Romantics; a discourse that extends into Modern and contemporary art. Like Shakespeare, Milton was an important literary reference point for the Gothic painters. So were some of their contemporary writers auch as the young Goethe (Werther), E.T.A. Hoffmann (Der Sandmann) and later Anne Brontë (Wuthering Heights) and Edgar Allan Poe (The Rise and Fall of the House of Usher, The Raven). Conversely, Mary Shelley’s novel Frankenstein includes a description based on Fuseli’s painting The Nightmare, by which it was partly inspired.

Dark Romanticism stimulated a range of ekphrastic dialogues that oscillate between literature and paintings/drawings and span great historical and geographical distances. They sometimes also include sculptures. On display at the end of the Auckland Art gallery’s mezzanine floor is a bronze statue of the archangel Michael overcoming the Serpent/Satan (Satan dismayed, ca. 1852) by Henry Armstead, an ekphrastic intertext to the biblical books of Genesis and Revelation.

Artistic interpretations of Edgar Allan Poe’s supernatural poem, The Raven, for instance were produced by Edouard Manet (illustrating the French translation of Poe by Mallarmé); but also by Gauguin who transposed the dark northern hemisphere bird to his 1897 painting, Nevermore, painted in the South Pacific to which he first escaped in 1891.

The popular ‘Gothic’ symbolism of ravens, owls and flying witches also plays a prominent role in some of Goya’s printmaking that is shown at the exhibition. The Auckland Art Gallery can call on a fine inhouse collection of the Spanish artist’s etchings.(4) The etching Volaverunt (Latin, ‘They have flown’) depicts a flying woman, her arms and coat spread like a bird’s wings. Other interpreters have compared her flight to that of a vampire, or a butterfly. Several men who can be identified as court officials peek out from under the hem of her skirt. With her spread legs and wearing a prostitute’s garment, Volaverunt may refer to a ‘femme fatale’, perhaps with a biographical dimension that alludes to Goya as a piqued lover of the Duchess of Alba.

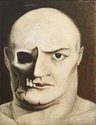

Tony Fomison would have to be New Zealand’s ‘Mr Gothic’, par excellence, and the show would not have been the same without him. He was probably the first choice of the curators who arranged and commented on all the images with expertise and wit. Macabre, ghoulish, grisly and downright ghostly probably sums up the nature of many of his works, issuing from a man who himself exhibited certain unearthly tendencies.

Stock-in-trade of the Gothic practitioner, of course, is the skull, the bread-and-butter motif that gets the spooky and ghastly juices flowing, and Fomison doesn’t disappoint. His Skull Face, 1970, plays it for all its worth with this podgy pale faced cadaver-like figure, staring out at the viewer (half skull, half face) to make his point. Indeed, he confessed that he hoped paintings like this would fester on the walls of his middle-class clientele, and that at some point they’d be forced to take them down and hide them behind the piano. Memento mori is only the half of it. Interestingly and apposite, Fomison’s rotting, Dead Christ, (after Holbein), 1971-73, features in the gallery’s salon (with Guo Pei ‘taster’) show next door, directly across from the skull work. The curators have thought this out well.

A little less ghoulish, but with the same preoccupation with death, is Megan Jenkinson’s, Romantic Rebellion, silhouettes of amphora-shaped urns, repositories for the ashes of the dead, burgeoned with leaves and foliage, as if some kind of denial is at work, or hope for a resurrection of sorts through the organic forces of nature.

The Romantics, particularly poets like Wordsworth, came with an assurance in the powers of nature and that we ourselves came, “trailing clouds of glory”, providing hints of immortality. In good Romantic fashion, where death becomes an exaltation, partaking that of the sublime, and thus made beautiful, Jenkinson’s works fit the bill. No Fomison morbidity or dark gruesomeness here.

Although the exhibition offers a good general overview of the topic given the limited space of the mezzanine, several New Zealand painters such as Jason Greig, Seraphine Pick and Peter Madden, but also photographers including Laurence Aberhart and Yvonne Todd, are unfortunately not featured. The same goes for film and video productions such as Sam Neill’s groundbreaking documentary Cinema of Unease, 1995. Still, as said, it is a good general overview.

Norman Franke and Peter Dornauf

(1) https://www.aucklandartgallery.com/whats-on/exhibition/gothic-returns-fuseli-to-fomison

(2) Henry Fuseli. In: Christopher Frayling, Nightmare: The Birth of Horror, London: BBC Books, 1996, p.6.

(3) Shakespeare, Macbeth, Act 1, Scene 1

(4) https://www.aucklandartgallery.com/explore-art-and-ideas/artist/2517/

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.