Errol Shaw – 7 September, 2024

I find The Suter Art Gallery website opening line, “Kia Ora, Welcome Welcome to the Suter Art Gallery - where art matters” irritating. Surely by now we have come to a point that if art does matter, then the need to provide optimum conditions is imperative in allowing the viewer to respectfully engage with all exhibitions, and for each exhibit to exist as an independent entity.

EyeContact Essay #53

Five years ago, Billy Apple The Politics of Space, an exhibition, or rather two exhibitions, Institutional Critiques and Gallery Abstracts at the Suter Art Gallery Te Aratoi o Whakatū provided something unexpected and something I suspect undetected. Curiously, it was also an assembling of two rather disparate cultural entities, a nationally and internationally recognised artist participating in an established conservative regional art institution. However, in my view, and most certainly not shared by many others, is the impact and continuing relevance of Billy Apple, an artist without peers, working in Nelson over the last decade or so.

What is of interest here, at the Suter Art Gallery, are the two purposefully designed galleries, the Ann and John Hercus Gallery and the Potton Family Gallery which accommodated Institutional Critiques and Gallery Abstracts respectively. On display, Apple’s works specifically critiqued other institutions, mostly subtractions or alterations by scrutinising the actual spaces and providing explicit solutions. Disappointingly, the two Suter Art Gallery spaces in which he exhibited bypassed his experient and discerning practice. However, hitherto unforeseen, a remarkable situation presented itself for the attentive viewer: each exhibition in fact became something akin to a picture-within-a-picture situation, the displayed institutional critiques become models, references or possible conceptual templates in which to view these galleries. In effect, it was feasible for the inquisitive viewer to likewise adopt Apple’s strategy and apply a do-it-yourself exploration of these problematic gallery spaces.

At a floortalk, in the Ann and John Hercus Gallery, Apple candidly talked to a receptive audience about the origination of his gallery critiques. With no set plan each outcome, each work emerged as a response to a given space. Before commencing any work he requested the spaces be cleared, and they were, but not cleared to his exacting standards. The spaces themselves became his centre of attention, so that any clutter, obtrusive features or defects, according to his displeasure or sensibilities, were proposed to be either removed, altered or replaced. Through such actions around the country he gained some controversy, as he remarked in a matter-of-fact way that he gained a reputation, as a Mr Fix-it. His interventions were simply physical, pragmatic and practical outcomes to individual spaces, an obsessional pursuit to fundamentally make spaces better places for showing art.

Quite surprisingly, Apple talked favourably about the spaces but equally surprising was a comment from the audience, “what about the carpet?” This was possibly a response to my previous EyeContact essay, The Exhibition Programme of the ‘New’ Suter. Somewhat hesitantly, he replied that he didn’t mind the neutral colour. He went on to say that he liked the proportions of the galleries and some architectural details, but the fragmented sectional wall areas, generous openings providing multiple exits had somehow escaped his critical attention. By taking cues from Apple, by using his adopted perception and strategies, I too was led by close looking, scrutinising the actual Suter spaces, both physical and social and to question what the architects, the Suter governing body, and what even Apple may have overlooked, or ignored.

Shortly into his floortalk, persistent and disruptive foyer and café noises penetrated the gallery, only to create hearing difficulties. By closing the adjacent sliding door, and for about half an hour, this part of the gallery was transformed into a contained, better functioning gallery space. For that brief moment, unexpectedly, this created a one-off Suter experience, an enclosed localised unified space blocking out sunlight, foyer and garden vistas and operating as a partial sound barrier. This demonstrated another overlooked aspect the architects failed to identify, that galleries also function as acoustic spaces, and open plan designs are inevitably susceptible to any unwanted and intrusive foyer sounds including the programmed music, café noises and any neighbouring sound based works.

Firstly, a brief description of the three 2016 redesigned Suter Art Gallery layouts: a reconfigured Bishop Suter Memorial Gallery; and new purposely built galleries, the Ann and John Hercus Gallery and the Potton Family Gallery. They are all aligned to a pervasive visual passageway, continuing through to the Nelson Suter Art Society Gallery, and all of these four connecting gallery spaces run parallel to the Jane Evans Foyer. By disregarding any transitional zones, each gallery relinquishes its independence to an unforgiving structure with multiple entry and exit points, generous open doors, and a physical and visual free-flow experience, affirming the foyer as the Suter hub that ultimately leads to the popular Suter destination, the Suter Café. The Ann and John Hercus Gallery and the Potton Family Gallery functionally fail as gallery spaces on a number of accounts: two ‘purposely designed’ galleries fracture the seven walls with obtrusive doors and openings, leaving just a single continuous wall. And the previously mentioned brown carpeted floor insistently drains the life out of any subtle works. The low conspicuous lighting tracks and surrounding architectural features hover and impose themselves by encroaching upon the space required for large works. The architecture, ever present, self-asserting, always dominates. The viewer cannot escape.

Probably the only photograph in circulation representing Billy Apple: The Politics of Space is the one accompanying Lachlan Taylor’s review in Art New Zealand.(1) This installation photograph, a single image showcases two Gallery Abstracts. Systematically constructed, the installation shot depicts the gallery as if a tableau, a framed closed space free from outside influences, conforming to what Brian O’Doherty expounded in his highly influential Artforum article, ‘Inside the White Cube: Notes on the Gallery Space.’ O’Doherty comments, “The installation shot is a metaphor for the gallery space.” (2) The scene is set for the purpose to be photographed; viewers are absent, seating is temporarily removed, and more importantly, for the first time, at the artist’s request, the door between the Potton Family Gallery and the Suter Art Society Gallery was intentionally closed to establish an autonomous space.

The photograph conveys a sense of stillness and silence, but outside this static depicted space, behind the photographer, a large open door contiguous with the foyer permits the outside world, the bright sunlight, the picturesque views of the Queens Gardens, and the incessant foyer and café noise, the background music to infiltrate the gallery and to ultimately distract and disengage any purposeful viewing and meaningful involvement.

Inadvertently, it is the door in the photograph that emerged as an intriguing active player. In an attempt to contain and isolate his two exhibitions from other exhibitions, Apple requested this door, and also its counterpart, the opposite door where the Ann and John Hercus Gallery and the Suter Memorial Gallery connect, to likewise be closed for the duration of Billy Apple The Politics of Space. But this door, the preferred entry for the Nelson Suter Art Society visitors, generated problems; by being closed it signified an art society exhibition change-over was in progress. A few weeks into Apple’s exhibition, a sign “Please pull the sliding door to continue through to Gallery 3. Billy Apple: The Politics of Space” appeared on a movable stand in the passageway between these two galleries. Presumably, this was a Suter ‘housekeeping’ issue, an operational matter, and most likely, without the artist’s consultation.

By not adhering to the sign, visitors, unwittingly, became participants, for their actions predetermined the conditions by which others would view the paintings. Gallery Abstracts represented scaled configurations determined by the actual gallery floor plans, highlighted with coloured shapes denoting utilities, plumbing, electrical wiring and other physical intrusions and as such appear as quirky irregular block-like abstract paintings. The Potton Family Gallery provided, once again, another extraordinary occurrence, another ‘picture-within-a-picture’ type situation; in this instance, a physical interference within the same field of vision, a visual overlay where the viewer could actually detect the Suter utility areas while simultaneously observing Apple’s painted critiques of other gallery’s utilities. Even through a partially opened door, a small passageway and the service spaces became clearly visible; to the right of this thoroughfare, doors of a then out-of-circulation lift and a storage cupboard could be sighted, and to the left, a door to the disconcertingly located toilet facilities creates a potentially awkward space by bringing a private space in such close proximity to the public transitional and exhibition spaces.

Undoubtedly, the descriptive exhibition sheets provided excellent information to assist the viewer in navigating the different interventions. However, an oversight:: two fundamental graphic errors are detected in the accompanying gallery plans; the left wall on Gallery Abstracts exhibition sheet and the right wall on Institutional Critiques sheets are clearly identified as continuous walls, which they are not. In short, the diagrams only include the foyer entry and the open doorway that connect the artist’s two exhibitions, basically rendering them as two ‘white cube’ configurations, and if realised, would certainly improve the exhibition spaces.

Returning to the installation shot; Gallery Abstract 1:3, 2006, exquisitely placed, dominates the photograph. Unfathomable at first, this large irregular configuration made more sense when reading the accompanying information sheet describing the blocked-in floor plan, the dimensions corresponding to a third of the Michael Lett Gallery, a collaborative work between gallerist Michael Lett, his then employee, Ryan Moore and artist Billy Apple. A perplexing abstract silhouette; flat black acrylic paint on unprimed canvas, unframed, yet exquisitely framed by the flat white painted wall.

Presented at The Suter, on the only uninterrupted wall, the painting looked stunning, except for an irritating intrusion, an exposed 10mm wide floor to ceiling inserted expansion joint that bisects and violates the only functioning continuous wall into two equal sections. Furthermore, the gallery lighting highlights and exposes the fixtures three dimensional qualities. To add, similar expansion joints are generously installed throughout the galleries, particularly around doorways to accentuate, decorate and showcase the architectural features.

It seems rather puzzling that an artist whose critical art practice, whose politics of space, so intricately involved with an obsessive attention to detail would have allowed Gallery Abstract 1:3 to be subjected to such architectural interference. The solution to this Suter problem is really quite simple: the offending joint can easily be covered with a flexible filler compound to create a permanent continuous wall surface. Until this is effectuated, the expansion joint persists in asserting its presence into every exhibition. Once seen, it cannot be unseen.

I find The Suter Art Gallery website opening line, “Kia Ora, Welcome Welcome to the Suter Art Gallery - where art matters” (3) irritating. Surely by now we have come to a point that if art does matter, then the need to provide optimum conditions is imperative in allowing the viewer to respectfully engage with all exhibitions, and for each exhibit to exist as an independent entity. Unsympathetically, the presentation of collection-based exhibitions at The Suter, are regularly displayed in chock-a-block clusters, only to create a confused clutter, a contest where each work is forced to compete for attention.

I would like to respond by mentioning a book, interestingly titled, Art Matters, in which Peter de Bolla identifies the importance of the encounter, a sensation of presence, a direct private experience of each artwork when it is exhibited in a public space. Furthermore, he values art in the social context and the possibility in sharing experiences, worlds, beliefs, and differences. He stresses the conditions in seeing art within an institution, “This canvas, this paint, this wall, this museum, this space determine our address to any painting, and similar material considerations are operational in our responses to any work of visual art.” (4)

The Suter building fund raising brochure declared, as I noted in my earlier EyeContact essay [#19] warrants repeating here; “They gave us a gallery for the 19th century, we need a gallery for the twenty-first century.” Yes, we certainly do need a gallery for this century, an architectural structure that allows art, in all its diversities and complexities to be respectfully presented, but we failed to get one.

Published in the Museum Aotearoa Quarterly, April 2019, Julie Catchpole, the Suter Art Gallery Director, outlined her vision for the Suter, “The gallery’s name recognises Nelson’s second Anglican Bishop Andrew Suter (1830-1895) who had a vision for a ‘Picture Gallery for the people of Nelson.’” (5) And she concludes; “The original gallery was earthquake strengthened and sensitively restored, today continuing to fulfill its purpose as a ‘picture gallery’, The Suter is now fully accessible and far more integrated with its beautiful setting.” (6) It seems likely that Bishop Suter’s vision has now been achieved.

This now inevitably draws attention to the expectations of governance, The Suter Art Gallery representatives and their responsibilities as custodians and cultural gatekeepers, for it is their decisions that determine all aspects of the institution, notably, the exhibition programs, collection purchases, public programs, archiving, publications and of course, providing acceptable exhibition spaces. It is worth mentioning Andrea Fraser, an artist whose art politics inextricably involves critiquing the institution. In her Artforum article, ‘From the Critique of Institutions to an Institution of Critique’ she contends that the complexity of art and the art institution necessitates its wider conception, the social field, a public context that includes different players and participants.

I must admit, I wished I had written what Fraser asserts; “It’s not a question of being against the institution: We are the institution. It’s a question of what kind of institution we are, what kind of values we institutionalize, what forms of practice we reward, and what kinds of rewards we aspire to. Because the institution of art is internalized, embodied, and performed by individuals, these are the questions that institutional critique demands we ask, above all, of ourselves.” (7) Fraser’s plea is serious, attentive, active, passionate, engaging and a call to action; but these attributes are possibly outside the inclinations and interests of Nelson’s public art sphere.

Now for some good news, and possibly, some bad news. Always inquisitive, Billy Apple at some time would have discovered The Refinery ArtSpace, a Nelson City Council controlled community gallery when it was operating in Halifax Street. Through incremental modifications, often instigated by artists, this 1930s brick building, formerly the Nelson Company factory, was transformed into a much-loved alternative art space, providing excellent exhibition possibilities. Recognising its attributes Apple proposed two small alterations for these two flexible and art sympathetic spaces, arguably, the foremost exhibiting spaces in Nelson.

Firstly, in the smaller gallery, The Opening: An Institutional Critique 2019, Apple proposed a small section of the gallery wall to be extended and connected to an aligned post, thus constructing a more cohesive enclosed gallery. For The Corner: An Institutional Critique 2019, in the larger gallery, Apple requested an irksome unused boxed-in corner structure to be removed. The two completed elegant solutions, simple physical alterations successfully upgraded the exhibitions spaces. Unfortunately, earthquake requirements, necessitated by the Nelson City Council, have subsequently resulted in closing these spaces.

An alternative, makeshift building, is currently being used for exhibition purposes, but to lose those two incomparable functioning spaces, would be yet again become another major loss for the visual arts in Nelson. However, unexpectedly, a recent Nelson Mail front page article headlines, “Old Refinery building could be pulled down.” revived some interest. (8) At this point the Nelson City Council’s Long Term Plan draft documents whether to strengthen it, or pull it down. Fineline Architecture director Magdalena Garbarczyk is reported as preferring to restore the Refinery. She said, “The Long Term Plan articulates Whakatū Nelson’s vision as a creative, prosperous, and innovative city. There is nothing innovative about demolishing a building.” (9)

Throughout discussing Apple’s involvement at the Suter Art Gallery I have been somewhat hesitant in mentioning, Correction: An Institutional Critique 2018, his only Suter Art Gallery critique. And for good reasons, because this site-specific work, which shared the same floor space that the two galleries for Billy Apple The Politics of Space inhabited, is simply, a disappointingly minor work. By scrutinising the recent Suter architectural plans, and also the original plans, Apple detected a slight inconsistency between the exact location of the nineteenth century Matthew Campbell School. Embossed lettering, “Matthew Campbell School Building Outline 1844” on the electrical floor cover plates were incorrectly placed. According to the Suter Art Gallery Collections Online, “Apple proposed that the inaccurate information be lasered off the floor discs, an action that was taken in the lead-up to this exhibition.” (10) Now completed, this work, without any signage or information is largely unknown, forgotten and remains lost amongst the interior visual clutter.

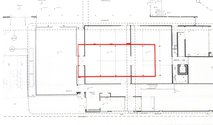

Accompanying this critique, Correction: An Institutional Critique (Scale 1:100), The Suter Art Gallery 2018, is one of two Billy Apple framed works in The Suter Art Gallery collection, and both gifted by the artist. The framed work is a black and white digital copy of the renovated Suter architectural plan showing the entire layout. Apple added a red outline to accurately identify the position of the Matthew Campbell School floor plan while red circles denote the embossed cover plates. This slight mismatch is no more than a polite critique that documented unimportant discrepancies. Unlike Apple’s exhibition information sheet plans, it is the architect’s plan that fortuitously reveals and accurately documents the problematically designed Suter exhibition spaces.

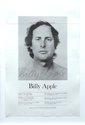

However, it is the second work, Billy Apple 1975, a signed poster, gifted in 2000, that transpires as a significant work in The Suter Art Gallery collection. While writing this essay the said piece had been exhibited along with other Suter portraits in their collection based exhibition, Let’s Face It, curated by Julie Catchpole to celebrate the 125th anniversary of The Suter. Positioned in the gallery space, Billy Apple directly faced Portrait of Bishop Suter, a 1902 posthumously commissioned oil painting by Mary Elizabeth Tripe. As expected, the painting label once again reiterated the message; “The Suter Art Gallery was named as a memorial to Nelson’s second Bishop, Andrew Burn Suter. He had a vision for a ‘picture gallery for the people of Nelson’.”

For my part, this public display had set up a conversation, inside The Suter Art Gallery space, between two contrasting, relevant Nelson cultural participants, born nearly a century apart. Now, what makes this Suter exhibition configuration so captivating is the curator’s positioning of Leo Bensemann Self Portrait to the right of Apple’s ‘self portrait’ as it strategically enters the conversation. Both exhibits are dated 1975. Set in the coastal scenery of his beloved Ligar Bay, this is possibly Bensemann’s last self portrait. He depicts himself in strict profile with a concentrated gaze and in Let’s Face It was positioned to be looking at the younger artist looking at the camera, and now precipitating in an artist-to-viewer encounter.

Billy Apple 1975 is a commercially produced black and white photographic image, a life-size frontal passport-like photograph. Spanning the sheet of paper and just touching his head, a conditional red line with instructions “Head shown actual size, to be hung at 5’ 7½” ” declares the artist’s political practice, a ‘height-specific’ request to either be adhered to, or not. Sponsored by the Queen Elizabeth II Arts Council of New Zealand in 1975 it lists his itinerary, a pivotal moment when the artist returned to the country of his birth, the first time in sixteen years, only to lead to further visits before residing here.

Originally intended as a poster to be displayed outside the gallery walls, Billy Apple, boldly signed in pencil and framed to the artist’s specifications, now participates within the Suter Art Gallery exhibitions. Silent, but still potent, Billy Apple is a Suter collection rarity, simply by being one of the few collected works that asserts its presence, offering an alternative to what is largely (as Grace Jones puts it in Corporate Cannibal) a “sanitised and homogenised” collection. Such works question and revitalise the Suter collection-based exhibitions which have been described as being “more tired than usual,” (11) and “staid and predictable.” (12)

Billy Apple is a much needed work for the Suter collection, its existence persistently reminds us of art in a wider, riskier, uncertain world, that exists outside the safety of the institutional field of vision. Uncompromising, defiant, this work is undoubtedly that of an outsider, once a renegade who is now a welcomed insider. Christina Barton’s final sentence in her Billy Apple obituary, published in the Nelson Mail on September 11, 2021 is a salient reminder to us all; “He wanted everyone to try harder, be better, to raise the stakes for art. We have a great deal to learn from the example he set.” Thanks Billy.

Errol Shaw

(1) Lachlan Taylor, “Billy Apple The Politics of Space,” Art New Zealand, number 167, Spring 2018, p. 47

(2) Brian O’Doherty, “Inside the White Cube: Notes on the Gallery Space, Part 1,” Artforum, March 1976, reprinted; edited by Amy Baker Sandback, Looking Critically: 21 Years of Artforum Magazine, 1984, p. 189

(3) https://thesuter.org.nz/ accessed 29 August 2024

(4) Peter de Bolla, Art Matters, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, London, England, 2001, p. 26

(5) Julie Catchpole, “Museum Profile,” Museums Aotearoa Quarterly, April 2019, p.15

(6) ibid. p.15

(7) Andrea Fraser, “From the Critique of Institutions to an Institution of Critique,” Artforum, September 2005, p.283

(8) Kate Townshend, “Old Refinery building could be pulled down,” Nelson Mail, April 22, 2024, p.1

(9) ibid. p.12

(10) https://collection.thesuter.org.nz/objects/1489/correction-an-institutional-critique- 1100-the-suter-art-gallery accessed 29 August 2024

(11) Mark Williams, “But the gallery [The Suter] itself was unchanged and the exhibitions more tired than usual,” review of Frances Pound, The Invention of New Zealand: Art and National Identity, 1930-1970 in The Journal of New Zealand Art History, volume 31, 2010, p.125

(12) Priscilla Pitts, “Whether deliberately or not, the exhibition [The River Lie] mounts something of a challenge to the staid and predictable Milk and Honey,” “Revitalised: The Suter Art Gallery Te Aratoi of Whakatu,” Art New Zealand, number 162, winter 2017, p.73

Billy Apple enthusiasts living in the Auckland region will be interested in the Apple exhibition currently being presented at Starkwhite.

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.