John Hurrell – 4 September, 2024

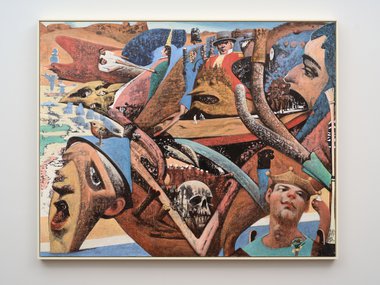

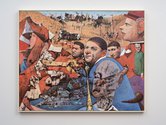

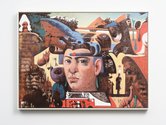

The resulting ambiguous shapes printed on the new surface—amorphous organic forms (sometimes Ernstlike decalcomania)—the artist then uses as a basis for improvisations, from which a resolved composition will eventually evolve. In terms of images, McWhannell at the start has no idea where the blotchy patches will lead. Usually, the resulting painting turns out to look a bit like a surrealist collage, with densely packed objects, figures and faces hovering unanchored in space.

In this intriguing new exhibition from Richard McWhannell, the works demonstrate a gradual painting process that extends over many months, an unusual chance-based technique generated initially from random shapes generated by one rectangular sheet covered with dark wet tarry oil paint being pressed hard against a primer or size-coated canvas.

The resulting ambiguous shapes printed on the new surface—amorphous organic forms (sometimes Ernstlike decalcomania)—the artist then uses as a basis for improvisations, from which a resolved composition will eventually evolve. In terms of images, McWhannell at the start has no idea where the blotchy patches will lead. Usually, the resulting painting turns out to look a bit like a surrealist collage, with densely packed objects, figures and faces hovering unanchored in space.

McWhannell happens to be a brilliant draughtsman, so this reaction against planning and its complex preparation by ignoring that talent, and focussing on extemporising (creating images within an ad-libbing format) takes courage. Curiously, while producing these spontaneous visages and assorted items, McWhannell usually has a subtle underpinning structure—a diamond placed over a saltire—discreet diagonals to keep the elements organised in vaguely balanced positions.

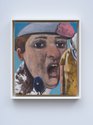

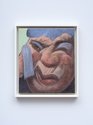

In these grainy, jumbled, tumbling compositions, McWhannell’s distinctive heads, figures and faces look as if they reference circus posters, Happy Families playing cards, the paintings of Bruegel the Elder or Richard Dadd, or the lithographs of Daumier. Sometimes, as if thrown onto collapsing piles and accidentally dumped in the paintings, some heads are muscularly contorted in their expressions (face-pulling that is not seen every day), and so seem like caricatures, making digs at commonplace human failings.

Beyond the heads and figures, the shapes of some of the human limbs and torsos have a slightly anamorphic quality, as if they might become more conventionally ‘realistic’ if the viewer shifted their position to (with more foreshortening) standing in front of the painting. Or else something straight out of Lewis Carroll/John Tenniel, with wormlike tubular limbs. McWhannell likes to tease, hinting that a resolution might be possible—or else bluntly shock via incongruity.

Amongst all these are distant dry hills, ruined buildings, skulls, breast-like hillocks, teetering monuments, and close up, delirious horses, conical tableware, robins, floating hats, circular arches and jutting landforms. Many are in fragments. In most the dominant hues are peachy pinks, greyish umbers and orangey siennas. The colours are hot, maybe referencing Spain, and these are invigorated by the ubiquitous presence of abruptly angular forms, mottled patches and the mentioned stretched-out elongated distortions, an eye-catching compositional dynamic.

These cluttered, often overtly bizarre paintings, have an appealing surreal strangeness, as if in a genre all their own where narrative is forced to explode. Akin to dreams, collage and rapidly receding memories, they cleverly celebrate human physiognomy with humour and understated horror, entertaining through wondrous variations, and at times within these unusual crowd scenes, pondering on ‘expressiveness’ by scrutinising the intricate contorting facial possibilities of our species.

John Hurrell

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.