Peter Dornauf – 29 July, 2010

But for someone so close to the action, it's a pity some of the bigger questions surrounding the artist are never broached. What, for instance, was fuelling this man's obsession with religious/spiritual conundrums in a country lousy with hairy armed pragmatists? Was there some Damascus event, some psychological trauma that took place in provincial Timaru eating away at this slightly built man? And second, was McCahon intellectually familiar with the writings of European theologians like Tillich, Bonhoffer and Bultmann who in the forties and fifties were wrestling with similar doubts and attempting to salvage something from the wreckage modernist thinking had visited upon religious belief at the time?

Gordon Brown

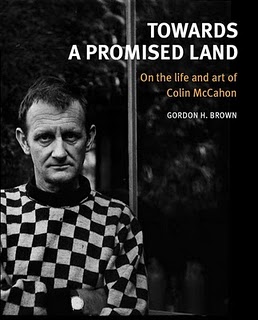

Toward a promsed Land: On the Life and Art of Colin McCahon.

Hardcover, 216 pp, colour plates and illustrations

RRP. $79.99

More books have been written about Colin McCahon than any other New Zealand artist, and quite right too. He’s our Elvis Presley and Bob Dylan of the art world in these parts, standing at the forefront of New Zealand modernism, a seminal figure who helped bring New Zealand kicking and squealing visually into the twentieth century. That there was huge reluctance on the part of most in this country to accept or even comprehend the new art vocabulary is common knowledge and Gordon Brown in Toward A Promised Land, refers to this hostility, most of it “asinine, bigoted and unworthy of serious consideration.” Brown speaks of the effects of that hatred, revealing that the hurt went deep for the man but suggests McCahon was probably his own worst enemy in dwelling on it, taking to drink to escape, which later brought on his descent into alcoholism. This was partly a product of the modernist paradigm itself where artists heroically offered their lives for their work in the forlorn hope it would somehow rescue civilization or save the world from perdition. It’s alluded to in the first paragraph of the book, where McCahon is recorded as famously saying that as a painter he was often “more worried about you than you are about me”, a line that now reeks of evangelical fervour. That accepted raison d’etre of the modernist movement would now be scorned by the postmodern pack. Back then modernists paid a high price for such an overreach and McCahon, along with a list of others, was a casualty.

The book is a collection of essays and floor talks that have already been published elsewhere in various guises which Brown has now edited, rewritten, plus added a few more and brought together in one engaging volume; an eclectic selection that slides back and forth between academic analysis and personal reminiscence. An insightful example of the latter is Brown’s first encounter with McCahon one evening in 1952 at his home in Christchurch. The McCahon’s lived in a modest unprepossessing small house next to the railway line where the glare of intrusive light from the shunting yards was pathetically thwarted by heavy thick blankets hung up across windows. Brown describes the noise of the trains, the soot and sulphurous fumes and observes how it was hardly a propitious setting for the Promised Land.

Such was the beginning of an enduring friendship between the two men that extended to sharing touring holidays with the McCahon family in the mid sixties. This close friendship gives Brown the inside running on the artist and it’s the books particular strength. He often draws on personal discussions with McCahon to help elucidate ideas and influences, whether they be Cubism, Woollaston or Uncle Frank. But for someone so close to the action, it’s a pity some of the bigger questions surrounding the artist are never broached. What, for instance, was fuelling this man’s obsession with religious/spiritual conundrums in a country lousy with hairy armed pragmatists? Was there some Damascus event, some psychological trauma that took place in provincial Timaru eating away at this slightly built man? And second, was McCahon intellectually familiar with the writings of European theologians like Tillich, Bonhoffer and Bultmann who in the forties and fifties were wrestling with similar doubts and attempting to salvage something from the wreckage modernist thinking had visited upon religious belief at the time? McCahon does quote Buber, but it would be useful to know if this was just pulled out of the air or whether he had actually read and studied the likes of Buber’s ‘I and Thou’, Tillich’s ‘The Courage to Be’ or Bonhoffer’s ‘Letters and Papers From Prison.’ How much the layman and how much the Lloyd Geering? [Editor: It is known that McCahon had a well-thumbed, personal copy of ‘I and Thou.’]

The chapter on McCahon and the theatre is a revelation. As a boy, the young Colin put on puppet shows for the family and in later life became involved in theatre productions, creating sets for satirical comedies and later the ballet. Photo’s survive for Peer Gynt and Swan Lake and sketches for other productions. It is fascinating to see how McCahon, like others before him who were co-opted into theatre productions (Matisse, Picasso) translate the modernist aesthetic into three dimensional sets. The influence of his landscape paintings in the late forties and early fifties is strikingly evident. It’s the photos that Brown has also managed to assemble that give the book that extra bite.

In a chapter dealing specifically with autobiographical matters, Brown writes of McCahon’s fascination with death, observing how it “assumed an exalted place in his work.” All the more poignant then that McCahon’s end should have been so merciless, sliding as he did into dementia. Brown recalls visiting him toward the end and observing him sitting staring vacant at the television set, become “a shell of the person I had once so affectionately known.”

This generously illustrated book will sit well alongside Brown’s classic work, ‘Colin McCahon: Artist’, first published in 1984. A valuable addition.

Peter Dornauf

Recent Comments

John Hurrell

I suspect the problem is not about artists emulating or parroting McCahon in their practices, but simply being unaware of ...

Andrew Paul Wood

That, methinks, would imply they had never cracked a general book on New Zealand art published in the last fifty ...

Kim Finnarty

I see what you are getting at John, current practice seems to be plugged straight into the mains. International styles ...

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 5 comments.

Comment

Kim Finnarty, 6:57 p.m. 2 August, 2010 #

Brown's book seems to fill the curious hiatus that we are experiencing in McCahon's posthumous career. The ACAG is shut for renovation and The National Collection in Wellington is eked out with a Catholic parsimony.

As these two are collections the two major receptacles for his painting we are currently experiencing a McCahon drought, a very dry valley indeed.

I hope the proposed exhibition space in Titirangi will work in conjunction with the residency programme at the McCahon cottage and the two major collections, to reinvigorate the McCahon legacy and the issues covered in Brown's book.

John Hurrell, 10:01 p.m. 2 August, 2010 #

I wonder if many of our readers share your sentiments, Kim. When I saw for example, the McCahon on the cover of the recent Francis Pound book, I felt our current period to be very far removed from the time when McCahon's work was dominating most art conversation in this country.Most of today's art students I suspect are not remotely interested in his practice, but perhaps that will change.

Kim Finnarty, 9:08 a.m. 3 August, 2010 #

I see what you are getting at John, current practice seems to be plugged straight into the mains. International styles rule and an art work only has to do its job in isolation, not necessarily as a coherent lifetimes work.

Seemingly mirroring the globalised, consumerist, disposable culture we are living in.

Art students are presumably not interested in McCahon's legacy because they are unaware of it.

Andrew Paul Wood, 6:36 p.m. 4 August, 2010 #

That, methinks, would imply they had never cracked a general book on New Zealand art published in the last fifty years.

Perhaps McCahon is simply a vast cultural edifice that has overshadowed NZ art for a very long time, and NZ artists have been trying to find their own identities in the light since at least the second half of the 1970s.

That is not to dismiss McCahon's importance - but when every Italian artist in the late 1500s tried to be Michelangelo, it only produced Mannerism.

McCahon is art history now, and the art historians would be better utilised promoting him in the global canon than shoving him down the throats of unwilling art students.

John Hurrell, 7:08 p.m. 4 August, 2010 #

I suspect the problem is not about artists emulating or parroting McCahon in their practices, but simply being unaware of his profound cultural contribution. It is much like a lot of the neo-sixties and neo-seventies stuff going on, where younger artists seem to be totally unaware of basic art history. They really do think they are inventing 'the wheel' for the very first time.

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.