Mark Amery – 29 May, 2011

By and large a whole host of artists who have emerged in the last five years have been left out. The picture doesn't look so different from that presented in the Auckland Art Gallery's survey of contemporary Maori art Purangiaho ten years ago. We're overdue for another survey then.

New talk of a National Art Gallery in the past year has obscured productive discussion about how Te Papa, as a combination of national museum and gallery , might better employ the national art collection throughout the building (nay, the country) in ‘telling our stories’. And, in so doing better introduce people to our art.

Isolating weaknesses in the Te Papa model we’re good at, but less so at celebrating when they get it right. Exhibition E Tū Ake is an outstanding example of what can be achieved by bringing museum and art collections into equal partnership under a potent theme. It demonstrates that such a model doesn’t have to deliver as banal a framework for discussion of identity as the museum’s opening Parade exhibition did.

Bringing together traditional and contemporary Maori artworks (twenty five of the latter in all) and cultural items, E Tū Ake is welcomingly direct and vocal in its expression of political purpose. The exhibition is an assertion of Maori self-determination. With a light touch it also tracks visually how contemporary Maori art builds on tradition whilst continuing to play a social and political role. It emphasises - take the beautifully designed waka ama and paddles included as example - that political identity isn’t all just about providing agitprop slogans.

“Tino rangatiratanga (the ability to choose one’s own destiny) lies at the heart of E Tū Ake: Standing Strong,” begins the exhibition blurb. The central promotional photograph by Michael Hall is of the tino rangatiratanga flag (created by the Te Kawariki Group in 1998) flying among different iwi flag within the mass of people taking part in the Foreshore and Seabed Hikoi in 2004. The incredible sight of those fluttering flags flying above us outside Te Papa dominates my memory of that day.

Refreshingly, the meaning of Maori sovereignty isn’t dissected or relitigated. It’s simply asserted as a fundamental right. Likewise, art like a recent Shane Cotton painting featuring a floating grisly Mokomokai (a stronger statement on the cultural treatment of such sacred taonga you’d be pressed to find) aren’t pulled apart as political statements. Rather, in this context it emphasises the continued importance in Cotton’s work of his Nga Puhi heritage as a living spiritual presence.

The way contemporary Maori artists are bringing new life to traditional Maori concepts and designs is a strong thread throughout. Joining a pounamu stone at the entrance is a Reuben Paterson black and white video work, presented within a display top like a pool of water. Geometric patterns bubble up from below, transmitting energy. Rather than just op art-inspired abstraction however (as we most likely conclude if its placed as usual in a pure contemporary art context) here the exhibition theme encourages us to discover that these were inspired by the pounamu stories of Ngai Tahu and their occupation and guardianship of Otago.

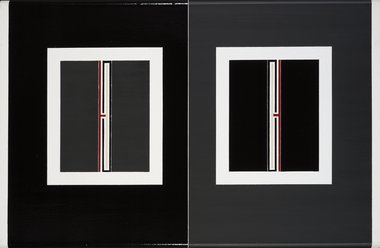

Paterson’s work visually anchors the beginning and end of the exhibition, and in amongst the carvings talks nicely to a Lisa Reihana moving image work that in black and white vigorously plays in the flickering ground between digital and analogue video aesthetics in a pulsating exploration of kowhaiwhai pattern (Len Lye is also recalled). It’s as if Reihana is making visible the ghostly traces of ancestors emanating through light out of the gaps between the weaving.

That contemporary artists might be leaders in asserting political ambition is signalled early on by artist Diane Prince joining other more well-known activist names in making a statement on the wall at the exhibition entrance. That artists speak here in a political context doesn’t diminish - as we often seem to have feared in recent exhibition practise - their work’s complexity. A Fiona Pardington image of a Hei Tiki placed in this context actually encourages the viewer to think more carefully about why such an artefact is being presented like this, and how photography and museum storage alters it.

In his paintings Darryn George plays off an international modernist abstract tradition as much as a traditional and modern Maori one. Yet his inclusion here makes us look at what makes his work different from Maori ideas, as much as how much he’s inspired by them. The museum environment gives them something to play off against. I love how here I’m drawn to the wrinkled white painterliness of his white lines. How they create an active expressionist abstract surface, yet are as carefully controlled as a Mondrian or the line of a chisel creating an active grooved surface in wood.

The traditional art displayed here was created as a public art - to be used in public ceremony, either to represent a tribe or the mana of the person wearing or wielding it. We shouldn’t be afraid to assert - as this exhibition does - that contemporary art operates in the same way in telling stories and providing emblems.

Brett Graham’s Foreshore Defender from 2004, included here, is a superb example. It is in the form of a stealth bomber or a moth, and whilst in its patterning might be initially taken to be a dislocated architectural feature from a wharenui, is actually on closer inspection made of rusted cast iron. Positioned like a flounder, I imagine it as a seabed version of a landmine, a loaded expression of Maori territorial authority.

E Tū Ake stands in stark contrast to the Slice of Heaven: 20th Century Aotearoa exhibition across the hall, where art seems to have been taken out of the picture almost entirely (as if to avoid any accusations of McCahons getting too close to Kelvinators). The notable exception is Michael Parekowhai’s cuisinaire block inspired Atarangi. It stands like an altarpiece at the head of an exhibition subset, ‘Okea ururoatia! Fight Like a Shark’ - a history of how Maori have resisted the “net of colonisation” in the 20th century. Parekowhai’s work stands in sight of the entrance of E Tū Ake and as such feels like a satellite of it. He’s an odd omission from the show otherwise.

Indeed my main criticism of the exhibition is what it has had to leave out. By and large a whole host of artists who have emerged in the last five years have been left out. The picture doesn’t look so different from that presented in the Auckland Art Gallery’s survey of contemporary Maori art Purangiaho ten years ago. We’re overdue for another survey then. E Tū Ake also highlights that this is just the tip of iceberg in terms of exciting less general exhibition ideas for a local audience.

I’d hope this may encourage Te Papa to place more exhibitions throughout the museum which tell stories valuable to us through art. What about New Zealand’s rivers for example? Or the New Zealand family? (Ironically given she’s just left Te Papa the Heather Galbraith curated Tender is the Night at City Gallery provides some inspiration here).

Interestingly, an exhibition put together by former Te Papa art curator Ian Wedde, He Korowai o Te Wai - The Mantle of Water at Rotorua in 2009, combining artwork from the Te Papa and Rotorua collections, also points the way (you suspect in part a Te Papa exhibition he never got off the ground there). Included in E Tū Ake from that exhibition is a video installation by Natalie Robertson concerning the Tarawera River and the effect of the Tasman Pulp and Paper Mill (I wrote about the exhibition and work in the NZ Listener here.)

After it closes at Te Papa this exhibition tours to the Musée du Quai Branly in Paris. It’s a credit to the curators that it feels as much for a local audience as an international one, and doesn’t just recycle Te Māori. Here at home however it also leaves the door wide open for exhibitions that might dig down even further, with even more focus on specific issues - and in doing so acknowledge a wider selection of contemporary artists.

In all likelihood the exhibition will get lots of attention in the media in New Zealand when it opens to acclaim in Paris. Pray it tours to other New Zealand and international centres on its way back, but meanwhile catch it while you can.

Mark Amery

Recent Comments

Martin Langdon

The one on the left, For God, For Queen, For Country is an operatic image of colonized Maori woman - ...

John Hurrell

Martin, where do you think Peter used the word 'Maorified'? Doesn't sound like him....

John Hurrell

Thanks for your supportive comments Martin. You will see tomorrow morning that Peter has a different take on things from ...

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 6 comments.

Comment

Martin Langdon, 6:11 p.m. 2 June, 2011 #

Although it can be compared as a stone to ripple the international art waters, its ripples may be the catalysis - that can be likened as the straw to the camel. Opening the flood gates of opportunity to the amazing abundance of talented contemporary Maori artist that were unfortunate not to be included. Much love

John Hurrell, 6:38 p.m. 2 June, 2011 #

Peter Ireland has some interesting thoughts on this subject in tomorrow's post.

Martin Langdon, 7:25 p.m. 2 June, 2011 #

Will be interested to hear his point of view.

Thank you John.

I wonder about the relevance and need 'in relation to globalisation'(no'z') to be received internationally, or is it a 'necessary evil' to feel 'received'?

I at times wonder how you can negotiate with people to change their lenses in order to truly evaluate contemporary Maori art. Especially considering that no 'traditional' exists - I like the terms Peter Ireland used like ' Maorified' and the quote used "there could be no such thing as contemporary Maori Art" Hirini Moko Mead. 'Dual ideologies' are now employed but interpretation of those rely on knowledge of connotative cues employed.

love the site keep up the good work :)

John Hurrell, 8:28 p.m. 2 June, 2011 #

Thanks for your supportive comments Martin. You will see tomorrow morning that Peter has a different take on things from Mark. All great for lively conversation. Here is Peter's blog. http://www.peterskite.blogspot.com/

John Hurrell, 1 p.m. 3 June, 2011 #

Martin, where do you think Peter used the word 'Maorified'? Doesn't sound like him....

Martin Langdon, 1:31 p.m. 4 June, 2011 #

The one on the left, For God, For Queen, For Country is an operatic image of colonized Maori woman - wearing a long “Maori-fied” Union Jack dress, a New Zealand flag draped around her neck, a decorated top hat on her head

Read more: http://eyecontactsite.com/2011/06/guerilla-girls#ixzz1OGbrYKe5

Under Creative Commons License: Attribution Non-Commercial

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.