Megan Dunn – 15 May, 2012

Different registers collide. That's all part of the Todd syntax. She juxtaposes words that normally don't get outings together; previous exhibitions include Goat Sluice and Iris Paste. Over time Todd has formed her own arresting and dubious language: from the faux-pharmacetical authority of Frottex and Drextel to the mawkish obscurity of Mousel and Mulkie.

Seahorsel Subset brings together the cast of an imagined sea side community and contains Yvonne Todd’s first forays into illogical movement; the epic pink swirl of a scarf, sand slipping through fingers, a variety of models in stilted and static poses, linked by a thread of seaweed or a clutch of driftwood.

Shown at Peter McLeavey in April this exhibition was a spin off from Seahorsel, Todd’s latest body of work that debuted at the Centre for Contemporary Photography in Melbourne earlier this year. Curated by Serena Bentley the Australian show juxtaposed Todd’s new work alongside The Wall of Man. In Wellington Seahorsel Subset was a local opportunity to share her new large colour images: the enigmatic Morton, the gripping Glue Vira, but also focused on a suite of small black and white photographs not seen in Melbourne.

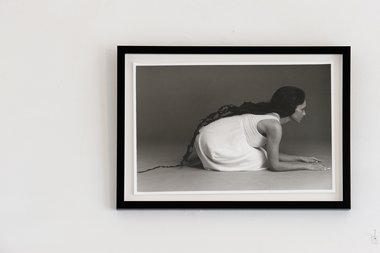

These additional images depict the same cast of models in a range of supplementary poses. The small images require a bit more sneaking up on, however, the scale and the shadows suit Todd: she’s an artist who knows how to beguile. In the front room of the gallery her black and white prints were hung in lines of three across one wall, big (almost toothy!) gaps between each frame.

Todd is well known for her perpetrations of anxiety and angst, her work frequently noted for its ‘not quite rightness.’ In Seahorsel Subset the artist turns her attention to signs of soul searching, that elusive state of inner calm, tranquillity. The inhabitants of this exhibition could be the members of a sect or a commune. In their white and beige outfits, the seventies chic of their billowing sleeves conjures up a whiff of Californian dreaming.

A beautiful young brunette in a white smock bends at the knees, she holds her arms out in an artificial pose, from between her fingers fall streams of sand. Her blue eyes meet us head on. Her loveliness is offset by the glibness of her stare. She could be a protégé of Charles Manson, a dreamy ingénue of the worst order. Her name is Sandy Cube.

Morton in his beige unitard posed with a seashell, probably wants to mediate with us. Why he’s wearing a velveteen goiter we’ll never know. Maybe that last tantric move got the better of him. Morton is Todd at her silliest. Of course humour is something we often don’t take seriously enough and the emasculation of Morton is jubilant. Does he sell seashells by the seashore? Placed before Morton on the surface of a white plinth, the pleated shell almost resembles a hand. The relationship of the body to the soul, like the man to the shell, his own fragile frame enhanced by the goiter, are all ripe for the picking.

Works such as Marthe II and Merril II are striking, classical compositions, the tension held in the coiled body, the erect pose. In these works shape and shade are enhanced by the black and white print. Marthe II is captured in profile, crouched on the floor, her arms extended in front of her in the formality and repose of a yoga move. She wears a black tangle of seaweed draped down her back like a hair extension. Merril II is the same male model seen in Morton. In his frigid flaxen wig he reminds me simulatenously of Sting and the actor from the old Beaurapaires commericals. Merril II wears a white bodystocking and a closed lipped smile. He gazes sideways out to the left of the picture frame, his hand held in a semi-salute, perhaps a participant in some benign form of fascism. He embodies the Aryan ideal, but is just as likely to be a weekend workshop guru offering his salute to the sun. The title ‘Merril’ recalls the word ‘merriment’ and there’s much to be had - as always - in an Yvonne Todd show.

Different registers collide. That’s all part of the Todd syntax. She juxtaposes words that normally don’t get outings together; previous exhibitions include Goat Sluice and Iris Paste. Over time Todd has formed her own arresting and dubious language: from the faux-pharmacetical authority of Frottex and Drextel to the mawkish obscurity of Mousel and Mulkie. The protruding teeth are part of her jarring dialogue, where we are ambushed by beauty, arm in arm with absurdity. Seahorsel is of course just seahorse with an L on the end. We’re talking Todd-lish here.

Moon Sap II is another new black and white image that plays on the eerie allure of a world draped in shadows, but is brought up short by the word sap, which is equally suggestive of the fool. This is an obviously ambiguous picture, the pair of dancers like Torvill and Dean, without the comforting link of romance, the female dancer looms in the foreground, the male is on tip toes, a lithe slant..

Glue Vira is clearly the title of an author with odd intentions. At one level the name is totally familiar, derived presumably (perhaps even subconsiously) from Elvira, Mistress of the Dark. Glue Vira is an orgiastic work, a show stealer. A pair of women are frozen in their beige body stockings like statues, upstaged by a flowing pink scarf. Their long hair, the rush of movement and line, the shadow self and its murky intentions, all combine to form an image as unforgettable as a pop chorus. In the accompanying Wall of Seahorsel catalogue Todd explains to Bentley that she always hopes for ‘…the one shot that is inexplicably more ‘special’ than the others.’ Glue Vira is it; a descendant of the equally imposing pink Fractoid (2004).

In Todd’s work the female (and occasionally the feline) face is frequently veiled in shadow as in Glue Vira or pixellated like the trio of women in Dance Gorgon Style. From Todd’s early un-Wuthering silhouettes in Asthma and Excema, to Fractoid on crutches, her cast of women resist the fullness of our gaze. (Often we literally can’t see the side of their face.) So are these shadowy women gorgons? The gorgon is a terrifying female monster, the name derived from the Greek word gorgós, meaning ‘dreadful.’

Todd’s gorgon dance does look a little dreadful to me. The anonymous trio each hold their stick of driftwood like a weapon. The women seem slightly heavy of foot, lined up in a row, in sync, their movement becomes more sinister, just as the commune has that dark and terrifying underbelly, expressed in the chant - the horror of the pack mentality.

I now move into a dangerous generalisation, yet I think it’s fair to say we expect mystery and nuance from fine art, the ineffable and the unknown. Todd is famous partly because she so richly provides on all counts. Her work is a sharp investigation of mystery and manners. She both embodies femininity and critiques it, her cast of women are sexy and strange, she’s serious and silly. In their frippery, her portraits sometimes even seem to mock our moments of depth. Perhaps it’s partly for this reason I so adore them.

At the end of ‘On Photography’ Susan Sontag concludes that the photographic image contains a ‘…potent means for turning the tables on reality - for turning it into shadow.’

So it is with the art of Yvonne Todd.

For fans - new and old - the pleasure is in watching her parallel universe growing.

Megan Dunn

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.