John Hurrell – 4 July, 2013

Ka Kata Te Po shows a black horizontal policeman (made of fibreglass) with a bull's skull (symbol for aggression), under attack from a spiky, pale green growth. The helpless figure is like an emaciated minotaur, and with the devouring prickly vegetation, both take on rich Old Testamant associations, such as a sacrificial ram found by Abraham caught in a thicket.

Auckland

International group exhibition and forums

If you were to live here

Curated by Hou Hanru

10 May - 11 August 2013

This post continues a series of thematic commentaries on the Auckland Triennial - its various presentations scattered over ten venues - this time looking at work that interacts with the historical consequences of colonialism.

Saffron Te Ratana, Ngataiharuru Taepa, and Hemi McGregor‘s collaborative project, Ka Kata Te Po, is a dramatic sculpture suspended over a AAG stairwell, that comments on the 2007 Tuhoe police raids and subsequent trial about activist camps in the Urerewas. The work shows a black horizontal policeman (made of fibreglass) with a bull’s skull (symbol for aggression), under attack from a spiky, pale green growth. The helpless figure is like an emaciated minotaur, and with the devouring prickly vegetation, both take on rich Old Testamant associations, such as a sacrificial ram found by Abraham caught in a thicket - or to extend the entangling bush image further, King David’s forces capturing his rebellious son, Absolam, caught by his hair in a tree.

Ka Kata Te Po is carefully positioned so it can be seen dead centre at the end of the Gallery’s Level One corridor, as well as from below or the side. Driven by community anger and indignation the work exudes a surprising emotional complexity and nuance. It is not a heavy-handed lambasting of police actions, but more a suggestion that they were thoroughly out of their depth, and pathetically stupid. On its back, the black figure looks vulnerable and overwhelmed. Monstrous but confused.

Allora and Calzadilla‘s Returning a Sound is a video of a moped rider driving a machine with a bugle attached to its exhaust. Raucously sauntering through the narrow Puerto Rican island of Vieques in the early morning, this noisy action, with its strangled piercing splutter, sardonically mocks the presence of the U.S. Military (its morning reveille routines particularly) and is a protest using civil disobedience (there is a curfew) against American colonisation. Two other videos continue this theme, plus there is a series of black and white photographs showing how specially gouged sandals worn on a local beach leave anti U.S. messages imprinted in the sand.

At Gus Fisher, Anri Sala‘s video, Tlatelolco Clash, is set in Mexico City in the Tlateloco region - with its pre-Columbian archaeological sites and mass graves from the period of the Spanish expeditions. It is also where a student massacre occurred just before the 1968 Olympics. In this dilapidated earthquake destroyed region Sala’s video concentrates on a ‘player piano’ barrel organ with its revolving handle and carefully perforated scores. Various people come and go, intermittently playing parts of a cardboard template of the famous Clash tune, ‘Should I stay or should I go?’- now recontextualised to become a pithy comment on the grim history of this location.

Another artist in the Triennial, Yto Barrada, is based in Morocco where she grew up, though she was born in Paris. Studying political science and history - before taking up photography - Barrada is therefore knowledgeable about Morocco’s colonial history, for in the nineteenth century it was divided into French and Spanish protectorates. This interview here is a useful filter through which to view her photographs (at Artspace) and posters (AAG), as well as her interest in particular locations like the Rif mountains, the political involvement of her family (she describes photographing a man who kidnapped and possibly murdered her grandfather) - or certain botanical forms she likes to paint such as irises, native to Tangier.

As is probably obvious, architecture is a crucial component of the Triennial suite of exhibitions, and much of the detailed discussion of certain local architectural projects has taken place in The Lab, on the top floor of Auckland Art Gallery. Its third section, Matariki Paparewa, involving UNITEC students and staff, exploits the gallery space and also the Viaduct part of Auckland waterfront, next to the ‘sixpack’ of silos where Ryoji Ikeda’s sound installation can be experienced. Leaning against the nearby gantry are a series of bamboo flag masts that allude to a Paparewa Teitei, an enormous seven-levelled structure built from kauri spars by Nga Puhi in 1849 at Kororareka. (It had various ‘hakari stages’ designed to hold and protect food - enough for a feast for 4000 - celebrating the arrival of peace in the region.) Seven other pennant poles reference the Matariki constellation, and the whole presentation is intended to honour recent Treaty settlements, especially for Tamaki’s mana whenua.

Out at Fresh gallery the colourful mural designed and executed by - going left to right - Rigo 23 (PT), Wayne Youle (NZ) and Emory Douglas (US) is very distinctive. It has three butted together sections that go around a corner: each reflecting the sensibility of each contributor in its content and aesthetic, though the artists have helped each other in the overall execution.

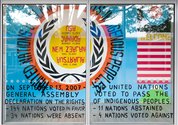

Rigo 23‘s section examines the voting record at the United Nations General Assembly on the charter upholding indigenous rights, noting the reluctance of delegates from the United States, Canada, Australia and New Zealand to participate. Though votes were first held on September 13, 2007, the motion wasn’t supported by this country until April 19, 2010. To get this information across the very large gallery window has been painted on as well as the moveable high wall (bearing the UN logo) behind it.

Wayne Youle‘s image is crisper and more elegant - though less literal, more poetic. It focuses on a blended American and New Zealand flag, shuffling parts around, changing colours, and imposing texts and hard-edged motifs - as well as faking a primary school classroom ambience. The section is poppy and precise, with ABC possibly meaning ‘Advance Coloured Peoples’ - and welcoming curious visitors.

The final section by Emory Douglas draws on his experience as the Black Panther Party’s original Minister of Culture and designer. He uses a vertical eight-shaped, infinity symbol, with incorporated koru and radiating shards, stating to the local community via text that ‘overcoming oppression is our path to unity.’ Whilst emphasising that countering racism is a means of developing collective self esteem and pride, it is curious that the three artists achieve a ‘path to unity’ only to a limited degree. There is no obliteration of their three selves in order to attain a dominant overall visual ‘brand’, and rightly so. The distinctions keep the work vibrant, sequential and focussed, without being too fragmented or partitioned - sections that successfully conceptually overlap and speak to each other - unpicking the destructive forces of history to stitch together a new world.

John Hurrell

Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.