John Hurrell – 12 August, 2013

In this new exhibition from Roger Boyce, the Christchurch painter, teacher and art critic moves away from Glen Baxterish social (or art historical) satire towards something conceptually like Allan McCollum (more than say Warhol) where sets of images - apart from variations in scale - initially appear identical, but where close scrutiny indicates otherwise.

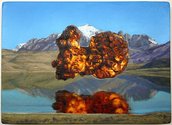

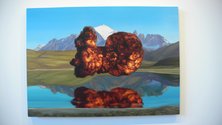

Boyce’s paintings come with four basic images ostensibly reproduced in three or four sizes, each variation creating its own bodily impact. The images are of massive rocks or balls of fire hovering above a reflecting lake, with rows of mountains and piercingly blue skies in the background. They present an otherworldly ambience as if inexplicable signs that have slipped in from another dimension. They bring a mystical flavour, an implied symbolism of possible cosmic consequence.

The work seems a blend of Magritte with Dali, as if these artists once lived in some treeless zone like in Central Otago, such as in a place like St. Bathans. Into these renditions of hauntingly beautiful landscapes the artist has thrown in a love of quirky visual texture and tonal manipulation, special effects for their own sake.

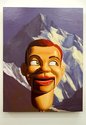

There seems to be a purpose to these images. By the gallery entrance Boyce presents two sizes of panel, three in each, all featuring the wooden head of a ventriloquist’s dummy set against different mountainous backgrounds and weather conditions. It is as if he is saying that climatic variables and qualities of landscape affect personality, a determinist instrumentality in the cause of human character. The face is nervously looking sideways, as if being coerced by larger forces above and behind.

The other types of work on display are non-portraits, in four suites of ascending sizes. They seem to be about individuality, a specific particularity in a visceral way, of how we experience each painted image through its size, surface detail, inflections of mood, and contingencies of meaning caused by subtly tonal accentuations.

In Oxford Comma, the patches of snow on dark scree slopes feature Escher-like bird shapes, or to the left, patterns like the thick stalks of silver-beet. The ball of fire seems demonic as if it’s a snarling bearded spectre hurtling horizontally through space.

Same Without You, in turn has flames that become a flaring map of Africa or a woman’s profile, her streaming hair like dangling strings of spaghetti. The entangled tubular flames have their own mesmerising intensity.

With Rock To Hide My Face, a stone phallus covered with moon craters hovers in front of limestone cliffs covered with mysteriously carved hieroglyphics. In the largest version the lake water has been disturbed so that the normally crystalline reflections are strangely blurry, as if recently disturbed.

The last type of image, What a Piece of Work is a Man, has an oily and smoky explosion where the churning flames seem like coils of greasy sheep wool. This makes its inverted reflection look like a waiting poodle, akin to something painted by Archimboldo.

Art of course doesn’t have to be mysterious or deliberately generate associations. Sometimes it is obvious and matter of fact, compelling because its very rationality has appeal. Boyce‘s images however are surreal and haunting and elemental. They generate an odd reverie like those created by looking into a fiery grate or bubbling stream. Meandering thoughts locked into Boyce’s own brand of verisimilitude.

John Hurrell

Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

This Discussion has 1 comment.

Comment

Owen Pratt, 8:57 p.m. 12 August, 2013 #

That was a bit of a cliff hanger; all's well that ends well.

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.