Warren Feeney – 9 March, 2014

Leek's work is very much about the fundamentals of a painter constructing pictures, and while this may touch upon the purity of modernist principles, Leek's sources are seventh generation. Here is a consideration of formalism enhanced by paint-by-numbers or cut-and-paste colouring-in books - sources for Leek that appear no less profound than Matisse or Picasso.

Spanning work from 2002 to 2014, Casual Arrangements is a survey exhibition of Saskia Leek‘s paintings in close pursuit of The Dowse Museum and Gallery’s 2013 exhibition, Desk Collection, which opened at the Dowse and also toured to the Dunedin Art Gallery and Gus Fisher Gallery last year. Notably absent from this new survey are the teenage narratives that characterised Leek’s work in the mid-1990s - the biro and oil paintings on coloured vinyl; works like Rollerskate Rescue (1995) and Coney Island Baby (1997). Yet the curatorial proposition for Casual Arrangement is more coherent than the Emma Bugden curated Desk Collection, revealing something further about the essence of Leek’s practice.

Desk Collection embraced familiar notions about Leek’s oeuvre that, while acting as an introduction for general audiences unfamiliar with her painting, tended to limit a wider awareness of the splendour of its gravitas. It opted for a chronological narrative tracking the development of her work through a Clement Greenberg modernist-mythology, the story of an artist’s progress from an iconography centred upon narratives to formalism and abstraction. It also gave weight to the ‘kitsch’ and outsider status of her imagery, while commending the small scale of her paintings for their modesty and irony. It was a welcome survey - Leek’s art is more than deserving of this attention - but it contexturalised her practice by reiterating ideas about the bigger picture of painting that had their moment on stage more than 30 years ago.

Leek’s paintings have had more than their share of attention over the past 18 months: a touring mid-career survey with contributing essays by three well-known curators; solo exhibitions at the Jonathan Smart and Ivan Anthony galleries; and now a second mid-career show, curated by a respected academic and arts commentator at the Ilam Campus Gallery. Arts professionals have accorded her an investment in research and publications that most artists can only dream about. So it seems reasonable to ask whether the curatorial investment has delivered.

In the first instance, it must be noted that Leek’s art is well-positioned for such attention, being an art practice that develops in the best art historical traditions from a figurative-based practice to a mature formalism. It is no coincidence that the Dunedin Art Gallery installed Desk Collections in chronological order, offering a story about an artist’s progress towards maturity and resolution.

And this may be a valid narrative about her work, but it also distracts from more significant aspects of her practice. Leek’s oeuvre is a visual paradox. The restrained filtering colours that began to typify her paintings from the early 2000s in images that often implied they were not particularly interested in engaging with audiences (for example Chrysanthemum, 2003, or the somewhat dour cat in Trance 2006), somehow liberated her paintings, allowing them to assume even greater control of the gallery space. An arts practice based on the premise that less is more, it was almost as though the smaller her paintings were, the more attention they commanded. Here is an artist orchestrating a practice that is far more perceptive and knowing than it might ostensibly appear - a body of work conscious of, and committed to, the act of painting that was conversant with, but also looked beyond, both modernist principles and post-modern irony.

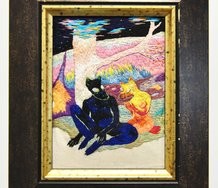

Leek’s practice maintains a healthy distance from that of a mocking commentary on kitsch or popular culture. Her treatment of source material from calendars, greeting cards and second-hand paintings in works like Sometime I’ll make the whole world laugh (2003) invites comparison with Colin McCahon’s use of the conventions of the comic book in his 1947-48 crucifixion series. While Roy Lichtenstein appropriated images by American comic book artists in the 1960s for his paintings to serve as ironic commentary on American culture, McCahon’s The King of the Jews (1947) exposes the artist as comic book fan and reader, perfectly comprehending its aesthetics and form as words and pictures. Likewise, Leek’s paintings possess an erudite affection for the paint-by-number images and objects she chances upon in second-hand markets, school-halls and community events.

Leek’s paintings represent an argument for subjective experience - childhood memories of beauty as something untouched by a ‘learned appreciation’ of aesthetics. Again, paradox abounds. As an arts practice that disarmingly gives dignity and affirmation to ‘beautiful losers,’ it is a theme succinctly touched upon in Bywater’s text in Casual Arrangements: ‘Leek’s work esteems the underdog. She turns us back for a second look, to appreciate not just the obviously visionary outsider, but to the way a refreshing awkwardness, or virtuosity… can be harboured within conventions, refreshing in the small differences they find inside those limits.’

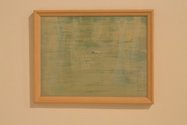

The diminutive scale of Leek’s paintings is also often misread as simply coy or intimate in their intentions. Again, surely the largeness or otherwise of a painting is not a measure of its intellectual and emotional potency. The modesty of scale and refinement of colour in, for example, Untitled, (from The Colour Course), 2013, invites favourable comparison with the work of artists like Michael Shepherd and Eion Stevens whose generally discreetly scaled work argues that painting should concentrate first and foremost on constructing images that command the viewer’s attention.

Leek’s work is very much about the fundamentals of a painter constructing pictures, exploiting colour harmonies, attention to surface, transparency, the complexity of spatial relationships and substance, and materiality of paint. And while this may touch upon the purity of modernist principles, Leek’s sources are seventh generation. Here is a consideration of formalism enhanced by paint-by-numbers or cut-and-paste colouring-in books - sources for Leek that appear no less profound than Matisse or Picasso.

Her works from the mid-1990s - featuring lacquered surfaces, shiny vinyl and a combination of biro and oil paint - suggest that her interests in painting’s potential have hardly changed, except to more consciously direct attention towards the ambiguous and shifting relationships between representation and the painting as object, with its own particular methodology of constructing images. Leek’s imagery currently has a tendency to spill over into the picture frame - a gesture that directs interest back to painting as construct, one that serves to both reward and intentionally deceive the viewer. The faux-collage silhouetted forms in Untitled (from The Colour Course) - grapes and leaves seem to be the artist’s favourite at present - imply a narrative, but only as a means of determining formal questions about space and composition.

Such painting assumes modernist principles, but Leek’s inelegantly sublime colour harmonies and asymmetrical compositions tend to argue otherwise. In Casual Arrangements Bywater reveals that Leek‘s art is as much a journal about the subjective experience of the artist’s world as it is a compelling case about the way in which painting continues its obsession with representation - while persistently raising questions about the making of art.

Warren Feeney

Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.