Andrew Paul Wood – 16 January, 2015

One does wonder, however, if criticising the obnoxiousness of the cartoons only a few days after the cartoonists were slaughtered by masked gunmen in their offices is a lot more obnoxious than the cartoons themselves?

EyeContact Essay #9

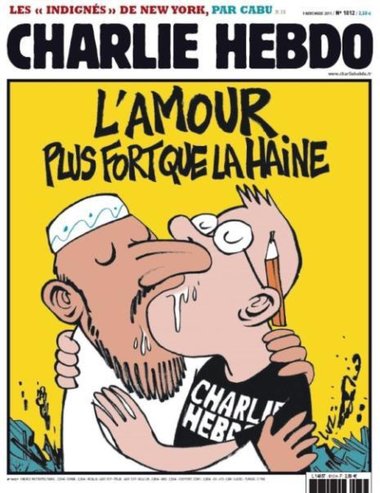

On 7 January 2015, two masked gunmen forced their way into the offices of the French satirical weekly newspaper Charlie Hebdo in Paris. They killed twelve people, including the editor Stéphane “Charb” Charbonnier, seven other Charlie Hebdo employees including the cartoonists Jean “Cabu” Cabut, Philippe Honoré, Bernard “Tignous” Verlhac and Georges Wolinski, and two National Police officers (including Ahmed Merabet, himself a Muslim), and wounded eleven others, apparently because of the publication’s satirical depictions of the Prophet Muhammad. Such depictions were pretty much par for the course as the main targets of the periodical were all things right wing and/or conservative in politics, religion (Catholicism, Judaism, Islam) and culture.

Of course you know all this unless you have been spending the last few days hiding under a rock in a cave on Mars with your fingers in your ears and your eyes closed. It saturates the media. One might argue that to mock Islam like that is to knowingly put oneself in the line of danger (there had been a previous attack in 2011), but that is racist thinking; it implies Muslim people are somehow irrational or intrinsically violent. Plenty of Muslim voices have condemned this atrocity. The incident has been used as a rallying call for the right of free speech as enshrined western values, but curiously little has been said about the licence of artistic freedom, which I will address in a moment.

To choose to relocate to a western country is a tacit acknowledgement of western values, including freedom of expression and secular tolerance, just as a westerner would have to think carefully before moving to a country with Sharia law. The Charlie Hebdo events have polarised two sides in a debate about expression and speech. On the one hand there are the rightish-leaning free speech at any cost brigade, who also harbour within their bosom a motley assortment of loathsome bigots who would very much like to speak their ignorant minds even if they have to countenance a backlash, and then there are the leftish-leaning who, now the shock has died down a bit, crawl out from the woodwork to remind everyone that Charlie Hebdo‘s caricatures were far from politically correct and, taken out of context, offensive. One does wonder, however, if criticising the obnoxiousness of the cartoons only a few days after the cartoonists were slaughtered by masked gunmen in their offices is a lot more obnoxious than the cartoons themselves?

Neither side would disagree that the massacre is a heinous criminal act of outrageous barbarity, but I have to bring up context again because what most of the latter group are reacting to are cartoons cherrypicked by the media to get a reaction from Anglo-Saxon sensibilities and divorced from their original context milieu of French political media and civic discourse. Quite often the most horrific cartoons were illustrations of terrible things Marine Le Pen and her Front National fellow travellers had said, in order to mock France’s toxic far right. To paraphrase W. C. Fields, Charlie Hebdo is (present tense, they march on) less bigoted than intent on insulting everyone equally.

Looking at the art world social media, the conversation has surprised me. The art world, myself included, overwhelmingly dresses to the left. It’s practically axiomatic. The default response has often been the politically correct one; condemn the terrorism, reiterate that free speech comes with responsibilities, and more than a little “Je ne suis pas Charlie” (shades of Magritte) in response to the well-intentioned-but-lazy platitude “Je suis Charlie” plaguing Facebook and Twitter with faux solidarity. Fine. That is freedom of speech too, the right to find something not to one’s taste. French gouaille (the typically Gallic, calculatedly outrageous cheek that can be traced back to mocking caricatures of French aristocrats being guillotined, if not all the way to the scatological, anti-Establishment ribaldry of Rabelais) is not for everyone. French Liberté, Égalité, and Fraternité are (due more to the intellectual descendants of Montesquieu than those of Voltaire) much more monolithic, assimilative and exclusionary than the Anglo flavour of the Enlightenment, but given the blunt nature of the visual arts as a method of social critique it strikes me as an odd position for an artist to take.

The problem is if visual artists (and here I include the glorious art of the cartoon) have to factor in the feelings of others, many a celebrated masterpiece becomes problematic. To begin with, some of the greatest fine artists are best known for what amounts to grotesquely offensive and cruel cartoons; Hogarth and Goya for example. Often the artists who have condemned Charlie Hebdo are the same people who were outraged when various Australian artists have been arrested or censored for exhibiting art that was interpreted by Joe Blow Aussie as child porn. If we are going to bandy around the notions of hate speech and offensiveness in the visual arts, where does one place works like Andres Serrano’s Piss Christ (calculated to offend Christian sensibilities), Dror Feiler’s Snow White and the Madness of Truth (vandalised by Israel’s ambassador to Sweden for supposedly being Anti-Semitic despite Feiler being an Israeli-born Jew), and Maurizio Cattelan’s meteorite-struck Pope and hanged children? Are Chris Ofili‘s paintings any less racial caricatures because we, the cognoscenti, know him to be of Nigerian descent? In the New Zealand context, were Jono Rotman‘s photographic portraits of Mongrel Mob members really all that controversial, and why did only Catholics get upset over Tania Kovats’ Virgin in a condom work at Te Papa all the way back in 1998? Should New Zealand artist Heather Straka employ security because of her “burkababes“ paintings?

Ultimately I don’t think it’s a supportable position for an artist to condemn Charlie Hebdo and their ilk without a sulphurous whiff of hypocrisy. Why shouldn’t this rather vague calculus of social offense be applied equally? One wouldn’t hold Peter Robinson to those standards for his liberal symbolic use of swastikas, so why exclude the jobbing cartoonist? Why indulge in the autobiographical fallacy with them and assume that what they draw is necessarily what they think? Is it snobbery? Perhaps it’s the idea that the editorial cartoonist is somehow more journalist than artist - which seems strange to me - as this was the reason the New Zealand Herald apparently gave for sacking Malcom Evans back in 2003 because some of his cartoons were supposedly biased in his criticism of Israel’s actions in Gaza.

In a parallel event, public opprobrium was levelled at another New Zealand cartoonist, Al Nisbet, for unflattering racial Māori and Pacific Island stereotypes, though one can’t help but observe that the Pākehā in the images are just as grotesque. Yet isn’t everyone made grotesque and exaggerated by the shorthand of caricature? Of course one can argue that it’s different when that distorting lens is applied to the more marginalised in our society, but intersectionality taken to its logical conclusion suggests that unless you are a financially secure, white, middle-aged, heterosexual, able-bodied, neurotypical cis-male (and they have their own demons), everyone is experiencing their own bespoke suite of oppression and marginalisation .

So where do you draw the line? Whose feelings get prioritised? What then are we to make of Ava Seymour‘s collages appropriating historical pictures of the mentally disabled?

Nietzschean/Kierkegaardian Ressentiment is a fallacious category for aesthetic criticism when it is laughed off as Philistine when applied to supposedly more nuanced fine art. Why should the cartoonist be expected to uphold journalistic impartiality and objectivity when the fine artist explicitly is not? In the case of Charlie Hebdo, who had the power? A bunch of aging white cartoonists with pencils, or a hit squad of masked Muslim extremist assassins armed to the teeth?

Here are my propositions: (1) the satirical cartoon, and indeed all graphic storytelling, falls within the fine arts family; (2) the cartoon, like the art gallery, should be regarded as a théâtre grand guignol where you should assume there is going to be a high likelihood that you will discover something there that you find unpleasant; (3) you have the right to your own tastes, but you shouldn’t dislike something until you have at least paused to consider the matter of context, nuance, and intent. As Aristotle said, “It is the mark of an educated mind to be able to entertain a thought without accepting it.”

Of course some things really are just outright offensive without merit, but they are usually crude and unsubtle, lacking irony or genuine humour, and asking nothing. They should always be condemned, but to quote Stephen Fry: “It’s now very common to hear people say, ‘I’m rather offended by that’ as if that gives them certain rights. It’s actually nothing more than a whine. ‘I find that offensive’ has no meaning; it has no purpose; it has no reason to be respected as a phrase… ‘I am offended by that.’ Well, so f****** what?”

Andrew Paul Wood

Recent Comments

John Hurrell

Here is a juicy quote from Stanley Fish's 'The Trouble with Principle', Harvard 1999, p.289: "...rational liberal theory with its ...

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 1 comment.

Comment

John Hurrell, 8:46 a.m. 19 January, 2015 #

Here is a juicy quote from Stanley Fish's 'The Trouble with Principle', Harvard 1999, p.289:

"...rational liberal theory with its abstract vocabulary of fairness, mutual respect, toleration, and so on is incapable of generating outcomes unless it is supplemented by the substantive considerations against which it defines itself. The theory project is coherent only within the terms of its elaboration as an academic enterprise, one populated by people who like to pose and present solutions to philosophical puzzles. Outside of that very limited content, theory - liberal or any other of the strong neo-Kantian kind - is without a purchase on any of the problems to which it might be applied. When a theoretical vocabulary does seem to be effective and to generate outcomes, it is because it has become a rhetorical vocabulary, a vocabulary already freighted with the assumptions of some or other agenda, although the work it does will almost be presented as proceeding from no agenda whatsoever but from the high plain of general truth or higher order impartiality. Theory, therefore, has no consequences except those that emerge from a political deployment of its terms, a deployment that can always be undone if another party seizes the same terms and molds them to its own purposes."

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.