Mark Amery – 18 March, 2015

Building up sections, sedimentary layer after layer, viewing these drawings can be an absorbing kind of archeological dig, an excavation of hints of figuration. Space collapses into a complex shifting weft and warp. Identifiable imagery morphs grotesquely out of shape, as if suffering a slow compression over time by the weight of things around it. Often I see rock faces, changing solidifying mountainous landscapes with fissures appearing to let issue streams of imagery.

The outsider artist comes with an extraordinary back-story to match extraordinary work. The outsider artist appears in Outsider Art Fairs and is largely championed by Outsider Art Curators and Outsider Art Dealers. The outsider artist’s name will be prefaced by the words Outsider Artist.

In this way the journey of an exceptional self-taught artist into the art world is only rarely one of coming inside. If they receive the rare distinction of having work purchased by a major public collection - as Susan Te Kahurangi King’s work in New Zealand deserves - the sheer distinctiveness of their work alone I suspect is likely to ensure an extra-large explanatory wall label.

As the exhibition of Martin Thompson’s work by Brett McDowell, Darren Knight and Robert Heald Galleries proposed, this can be different. And now, fresh from New York’s Outsider Art Fair and a solo show at its owner Andrew Edlin’s Chelsea gallery of outsider artists late 2014 (covered this month in Art in America), King’s pencil drawings are being shown at Robert Heald. There are no big labels, explanatory notes, accompanying book or documentary screening in the corner, just the work. We are invited to consider the art first, ask questions about the biography later. To appreciate it within the context of Heald’s stable of impeccably kitted out art school grads.

In other ways King is treated differently. This isn’t the artist’s recent work. It’s a selection of 24 drawings from an enormous collection from the late 1960s and 1970s (also the focus of international exhibition attention). Furthermore, rather than being spread around the gallery’s walls it is grouped together, rather elegantly, on one wall as a cluster. This suits the works layered, intense energy, yet at the same time stresses each work as part of a bigger narrative.

For Susan Te Kahurangi King’s extraordinary back-story, and discussion of the ethics of the work being shown, I direct you to Dan Salmon’s beautiful 2012 documentary Pictures of Susan (which you can stream here). In this review I follow the exhibition’s lead and focus on the work.

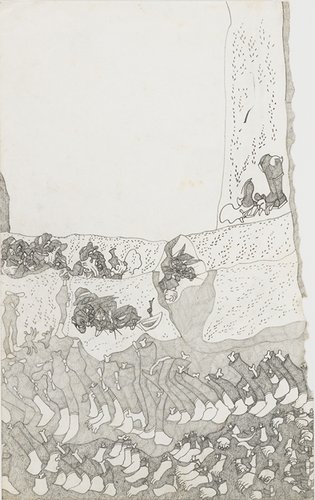

In King’s art the world turned cartoon has suffered a carnivalesque collapse. All those still frames made to run in fluid motion in old Disney animations have become unshackled from each other and merge riotously into a silly-putty mass. Within are rippling pile-ups of dismembered body parts and other less easily discernable elements, twisting in and out of a beguiling rhythmic abstraction that, Cubist-like, explodes perspective.

This astonishing work is as dark as it is delightful. Limbs and bodies push and pull together in and out of the shaded heaps. A dance in line, time has come undone. The world is being compressed into mangled layers of gesticulation. There is violence, laughter and tenderness all on the one page.

Building up sections, sedimentary layer after layer, viewing these drawings can be an absorbing kind of archeological dig, an excavation of hints of figuration. Space collapses into a complex shifting weft and warp. Identifiable imagery morphs grotesquely out of shape, as if suffering a slow compression over time by the weight of things around it. Often I see rock faces, changing solidifying mountainous landscapes with fissures appearing to let issue streams of imagery.

Rather than a graveyard of bones however there’s an intense muscular wrestling with life. Googly big eyes and sharp teeth, crooked fingers, fluffy bunny tails, sinuous repeating lines of lamp posts, voluptuous lines of legs, nipples repeating like lascivious punctuation - the hyper-dramatic vocabulary of the cartoon is reassembled as a personal code surreally fading in and out of resolution.

Often, there’s an orgy of figures. In one work figuration is reduced to what could be a bobbing field of Donald Duck bottoms. Bodies elongate or squat, collapsing elegantly into crystalline shapes. Drawing becomes a struggle through pattern with the mesh of love, desire, greed and fear.

Another appealing tension in the work is King’s choice often not to draw on the blank side of scrap paper provided to her, but to interact with a miscellany of documents on the other side. Speaking of their pre-digital time, these add a diverse surreality of their own - an advertisement for concrete cutting, or an invoice for hundreds cartons of lamb breasts and flaps. I’m told the artist can’t read, so the rich connections to be made between found text and images are probably accidental. Yet sometimes you have to wonder. Take the print out of the inside of a Wedding Day congratulation card - decorated with a surreal procession of increasingly dismembered nude bodies, hand gestures and facial expressions full of grunty impropriety.

Working on scrappy pieces of paper, full of blotches and scratches there are also tentative scribbles and incomplete textural areas. These become part of the works charge. Sophisticated patterns emerge from chaos, or vivid and faded variations on the same patterns sit together in strange balance.

In their decorative compacted meld of figures and abstraction the works can be reminiscent of ancient friezes, with hieroglyphics pertaining to momentous struggles. The subject matter though is often whimsical - if carrying a seditious, sometimes disturbing bite. Figures in underpants are common, and King seems to have a particular fetish for shoes. The propeller hat - that strange childhood American post-war icon - takes on a surreal life of its own, emblematic of King’s enjoyment of letting small graphic elements take flight.

References to Disney (or Warner Bros.) are easy to see, but the work is far more diverse. The approach to figurative elements is very varied and always accomplished, but there‘s also constant experimentation with how abstract elements might interrelate. In abstraction King can do things that feel completely fresh. Two drawings, for example, respond to a designer’s blank three-column grid, with a complex testing of space in shading, shape, line and colour over and behind the grid - with not a cartoon element to be seen.

Everything in her work feels like it is being squeezed. These images I think resonate today with the gradual violence inflicted on our bodies though mixed messages sent by a bombardment of mass media imagery. With their dark social wit, elegant dance of line, extension of the decorative, and energetic push of a body-based expression, King and contemporary painter Kushana Bush would make a strong pairing.

Mark Amery

Recent Comments

Connie Blue

Stellar work and beautiful install. There is room for this kind of art practice; I'm sure there are many artists ...

John Hurrell

Maybe this type of art may be seen as as an alternative (even an antidote) to a lot of practices ...

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 2 comments.

Comment

John Hurrell, 7:03 a.m. 19 March, 2015 #

Maybe this type of art may be seen as as an alternative (even an antidote) to a lot of practices (maybe most?) that emphasise conscious thought and planning? Is there room for artforms that celebrate impulse and bodily spontaneity, that see no reason to provide intellectual justification for their processes of production?

Connie Blue, 10:50 a.m. 7 April, 2015 #

Stellar work and beautiful install.

There is room for this kind of art practice; I'm sure there are many artists who are more involved with spontaneous mark making than planning and process.

It's kind of nice and refreshing to be given these drawings to look at, that don't have masses of intellectual justification. The mystery is there; it is intriguing. I think the works are emotionally provoking enough that we can always take something away from them internally, intellectually.

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.