Andrew Paul Wood – 23 April, 2015

The cruciform has been familiar in Bambury's work for some time. There is a painterly cheek to it in that the cross has a particularly heavy burden of symbolism in western art - even in stylised form because of the heraldic tradition, or Colin McCahon's tau cross paintings - yet as Leonard Bell described his work in a 1982 interview with the artist, Bambury's paintings “have no decorative, naturalistic, metaphoric or autobiographical references or intents - all elements which, in his scheme of things, are extraneous to painting.”

For two colours, e.g. to be at one place in the visual field, is impossible, logically impossible, for it is excluded by the logical structure of colour. - Ludwig Wittgenstein, Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus (1921), proposition 6.3751

Christchurch-born, Auckland-based abstract painter Stephen Bambury is such a prominent figure in contemporary New Zealand art that he needs little introduction, Urbis magazine in a fit of hyperbolic lily-gilding going so far as to call him “New Zealand’s leading contemporary artist” and the legal stoush with dealer Andrew Jensen has been tabloid fodder in the mainstream media. He is certainly one of the leading figures in New Zealand abstract painting and since the mid-1980s exhibited in the USA, Australia, France, Germany, Austria and Slovenia. He was a recipient of the inaugural New Zealand Moët & Chandon Fellowship in 1989, and this year will take up a Residency at Ateliers Höherweg, Dusseldorf, Germany. His exhibition at Christchurch’s Jonathan Smart Gallery doesn’t drastically break the mould, but it is a tidy and very fetching recapitulation of established themes.

Much of Bambury’s work is a direct response to Ludwig Wittgenstein’s rather obscure and fragmentary posthumous text Bemerkungen über die Farben (Remarks on Colour, 1951) in which the philosopher revisits Goethe’s Zur Farbenlehre (Theory of Colours, 1810). Goethe’s intention was a poetic rather than scientific rebuttal of Newton’s Opticks (1704), rejecting the Englishman’s observations on prisms and the spectral composition of light in favour of describing the way colours and colour relations are perceived by the eye.

Goethe’s “science” is, from a materialist point of view, bunk, but philosophically fascinating - that experienced colour is actually a product of the interactions of light (the ultimate white) and dark (the ultimate black), yellow being a darkened light and blue being a lightened dark. It’s an idea that fascinated philosophers, physicists and artists (Philipp Otto Runge, J. M. W. Turner, the Pre-Raphaelites, Seurat, Signac, and Kandinsky). Dualities are a feature of the way Bambury paints - hot/cold, light/dark, positive/negative - reminiscent too of the contrast exercises in Johannes Itten’s introductory art courses at the Bauhaus.

The idea of colour crops up repeatedly in Wittgenstein’s philosophy, particularly the idea of colour-space (the impossibility of a point in visual space having more than one colour at the same time) and the notion that colour is one of the defining forms of objects; an anti-theory of colour that rejects the possibility of it being a physical entity, but something phenomenological that only exists conceptually and experientially.

For Wittgenstein, colour, like Chomsky’s theory of language, is innate and built into immediate human experience, though the philosopher was quick to dismiss any hypothetical scientific or psychological elements. He was particularly critical of the traditional colour wheel, noting as gathered in his posthumously collected Philosophische Bemerkungen (Philosophical Remarks, 1964): “At any rate, orange is a mixture of red and yellow in a sense in which yellow isn’t a mixture of red and green, although yellow comes between red and green in the colour circle.” (1)

Orange paint is made by mixing red and yellow and lies between those colours on the wheel. Yellow lies between red and green on the wheel and yet we cannot make yellow by mixing red and green; the result is a muddy, faecal brown. The two colours obey different grammatical laws. This grammar of colour, thought Wittgenstein, was a word game consisting of subjective value statements like ‘cyan is lighter than navy blue’ and ‘the complement of red is green’, which is alluded to in Bambury’s palette choices and counterpoints, making us conscious that we really can’t describe his work except to participate in this game.

Bambury the peinteur-philosopher paraphrases Wittgenstein through his paintings; can we make a distinction between the colours of material substances and the colour of surfaces. (2) To use Wittgenstein’s example, gold is a “surface colour” (3) but while gold paint exists, Rembrandt didn’t use it to paint his Man in a Golden Helmet in the Gemäldegalerie in Berlin (4) and yet we still recognise the masters mix of pigments as analogous to gold. The difficulties inherent in any discussion of colour (for both Wittgenstein and Goethe) are a result of several related grammars of the sameness of colours (5) because when we compare colours, what is our point of reference? (6)

As far as Wittgenstein is concerned, we are merely describing the impressions of a surface to ourselves. (7) Bambury employs a number of strategies to investigate these interactions of grammar. Gilles Deleuze’s 1968 text Différence et Répétition, in many ways a subversion of the Kantian worldview, suggests that the history of philosophy has always treated difference and repetition as bad, derivative things only existing in relation to a unique entity somewhere (Plato’s ideal archetypes; the decline and fall model of civilisation, Marx’s paraphrase of Hegel that history repeats itself, first as a tragedy and then as a farce).

Deleuze recast repetition as an infinite, active reinvention producing difference, and while Bambury is no Deleuzian, a similar strategy is at play in his subtly variable iterations of the cruciform through colour, texture, material and angle of both cross and aluminium panel. Bambury has in the past referred to his works as “actualised objects” in reference to American painter Joseph Marioni; “The central issue of painting as an actualised object is not the colour of the object, but rather the function of an image whose objectiveness is colour”(8); Platonic forms actualised in experience and knowledge, finding identity between the domains of the real, actual and empirical.

The cruciform has been familiar in Bambury’s work for some time. There is a painterly cheek to it in that the cross has a particularly heavy burden of symbolism in western art - even in stylised form because of the heraldic tradition, or Colin McCahon’s tau cross paintings - yet as Leonard Bell described his work in a 1982 interview with the artist, Bambury’s paintings “have no decorative, naturalistic, metaphoric or autobiographical references or intents - all elements which, in his scheme of things, are extraneous to painting.” The geometric abstraction intimates that is that it is an arbitrary compositional motif, though in fact he deliberately riffs on the Christian connection in works like Fourteen Mirrors, a knowing, secularised allusion to the fourteen Stations of the Cross which showed at the Trish Clark Gallery in Auckland at the end of 2014.

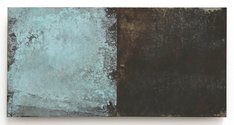

We see an earlier iteration in the work SC119866 (2011) where Moholy-Nagy’s constructivism plays off against Malevichian white on white. Foreground and background are inverted in Purple Rain (2015) where the precisely-skewed crosses (one needs an aesthetic spirit level) are created by tipping the corners of a rust field with imperious purple quadrants. The grammar of “surface colour” is subverted by Bambury’s mastery of gilding, metal, patina, rust, oil and other materials offering a painterly parallel to Rosalind Krauss’ “Expanded Field” for sculpture. The vertical diptych Ido Chawan (2013) - the title alludes to the elaborate glazes on Korean chawan tea bowls - is an essay in the discernments of colour grammar executed in Rococo rose with Byzantine gold quarters.

The cross works have probably been discussed enough over the years that we may pass over them quickly to more closely examine two other threads of the show. The exquisite Drawings on Secret Knowledge works in various pigments, pencil and gold leaf on Indian paper are a surprisingly light and delicate touch for an artist normally associated with robust abstractions with hard edges in durable materials.

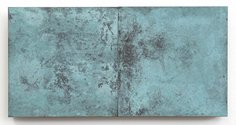

Then there are the small diptychs, the Tantra Song works and Seasons series; miniatures in a way, alchemical in spirit, produced by chemical action on copper plates analogous to a printmaker etching a plate. These, I think, approximate the essence of Wittgenstein’s ideas of colour-space and colour as form. Each consists of two pieces if the same copper, but each component is given a different patina, either verdigris or something darker, defined only by its opposite against the white wall. Their materials also tie them to the natural world, the elements and a simulation of the passage of time and take up a theme of binary alignments in Bambury’s work, his “two colour” paintings, going back to the early 1980s.

Andrew Paul Wood

(1) L. Wittgenstein, Philosophical Remarks, Blackwell, Oxford 1975, §219.

(2) L. Wittgenstein, Remarks on Colour, Blackwell, Oxford 1951, III, §254.

(3) Ibid, III, §100.

(4) Ibid, III, §79.

(5) Ibid, III, §253.

(6) Ibid, III, §78.

(7) Ibid, III, §64.

(8) J. Marioni, Painting as an Actualised Object, Miami University Art Museum, Oxford, Ohio 1979

Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.