Jodie Dalgleish – 22 June, 2015

Well laid out, the exhibition has its toes in the water of the Grand Canal and its entry in the respite of the Palazzo garden. Perhaps unexpectedly, given its diversity of artists, it is well-suited to the character and context of Venice. It is also bound by a common vision for the roaming and site-informed artist, and by an artistic language that is loosely informed by the playful and constructive behaviours of Situationism and the art of the dérive.

Veince

Nine Dragon Heads

Jump into the Unknown

9 May - 18 June 2015

Jump into the Unknown, presented by the international art collective Nine Dragon Heads is an eclectic, yet naturally cohesive exhibition that connects on the level of the individual and the meta-critical. Sited at the Palazzo Loredan dell’Ambasciatore, it is an official collateral exhibition of the 2015 Venice Biennale and marks twenty years of the collective’s projects. Well laid out, the exhibition has its toes in the water of the Grand Canal and its entry in the respite of the Palazzo garden. Perhaps unexpectedly, given its diversity of artists, it is well suited to the character and context of Venice. It is also bound by a common vision for the roaming and site-informed artist, and by an artistic language that is loosely informed by the playful and constructive behaviours of Situationism and the art of the dérive.

Come upon by following a short maze of lanes not far from Gallerie dell’Accademia, the Palazzo garden opens up to the monumental steel ‘tent’, or Nomadic Pavilion, of Alois Schild. As with other core artists in the collective, Schild’s work has a core concept and aesthetic that repeats and is revisited across continents. Not only a visual motif here, it is also a useful gathering and presentation space. Budding incongruously out of the Palazzo’s old facade, it houses an archive of material relating to the collective’s projects in Sarajevo, and the DMZ between North and South Korea, with information presented on sheets of matt steel, the same core material as that used by Schild.

Projected on Schild’s steel against the pavilion’s farthest side, I find a video that presents a montage of artists’ performances that have already occurred in Venice. This provides not only a useful background to some of the works, but also a materially engaging experience that befits Schild’s work, the exhibition, and the city of Venice itself. I am not sure why this materiality works so well in this city. I think it has something to do with the jewel-like yet uncompromising quality of the steel sheet’s surface-the way it beguilingly holds the light and softens details while its steeliness keeps you removed, at arm’s length. A sense of provisionality is also in tune, as sheets are moulded, mounted, propped, and leaned. They have an unpolished, almost unkempt, nature, which continues in the composite wooden sheets that line the once-grand interior of the Palazzo.

Schild’s Nomadic Pavilion also provides a lofty, yet not entirely comfortable, position for Dunedin-based artist, Ali Bramwell‘s work, Hollow Conductors, which, rather than being archival, is one of the most compellingly site-specific works of the exhibition. Well resolved and targeted, Bramwell‘s work both embodies and transforms the tools and processes of a service industry so vital to Venice. Using a hand truck as its portable armature, it directly references the multiple daily events by which rubbish is collected, streets are cleaned, and goods are transported by cart, all over the city. Loaded with aluminium foil-gilded items, including bucket, brush and pan, brooms and cleaning products, and topped with a theremin and protective umbrella (added later), it has paced the streets with the artist, and now records the act. Transported on May Day-International Workers’ Day when, ironically, only the cleaning and portage-based workers were working, it has rolled across and through calle, corte, fondamenta, and piazza, along house fronts, beside canals and under colonnades.

As shown elsewhere on video footage, Ali walks quickly, in a no-nonsense fashion, letting the trolley exist as the basic reference it is, letting the duality of its paradisiacal and mundane aesthetics sound, as indicated by the response of the theremin that responds in constant and varying proximity to the many surfaces of the city’s built environment. In Schild’s steel tent, it sounds on the afternoon I am there, as a constant high pitch, like a stone in the shoe, or a bug in the air, which seems fitting given the constant but supposedly ‘invisible’ and grand-scale process that keeps the, reputedly-beautiful, Venice clean.

Other work also references the roving and site responsive artist’s need for shelter and materialises the syntax of the yurt or tent. Although this is a little obvious, I enjoy Susanne Muller’s garden-based work, When the Stones Swim, Leaves Sink for the nature of its projection of ‘33 camera jumps under water’, and the way she uses her tent’s black interior itself to map them-even though the Venice heat makes it unbearable to linger. After submerging a GoPro camera in 33 sites, Muller presents what I read as a mix of cartographic notations and dark and mysterious organic patterns to create the tracery of being variously located. I can immediately relate this to my own engagement with the maze of Venice and the cartographic history of a city that, from the fifteenth century, was central to the construction of a Renaissance world view and the artistic depiction of urban detail. Projected on paper with the character of rice paper or parchment, the images feel archaic and tenuous, even fragile and inestimable, as if Venice’s water-borne status and future is indeed impossible to map and fathom.

Also in the garden, two other works explore Venice’s water-borne nature and dependencies. Elegiac but in dazzling sunlight is Gabriel Edward Adam’s, Pranzetto (translated as ‘a small meal, especially a delicious one’), which presents a traditional shallow rowboat once used for hunting birds in the Venetian lagoon. It has been brought in, decorated with the pattern of red and white gingham and shared as it most recently was, in a boat yard-inverted and used as a picnic table. In collaboration with Il Caicio, a local association dedicated to preserving water craft and social culture, the artist has enlivened a local artefact and brought it into the fabric of the collective’s own context. Also poetic, but with a, perhaps unintended, sense of foreboding is Sung Kyun Goo’s Santa Luce: a line-up of empty plastic raincoats with liquid hearts in their pockets. Transparent and bouncing back light, they convey a sense of loss, as if Venice has become the shell of its own need for the ultimately overwhelming presence of water.

Entering the Palazzo, Lim Hyan Lak’s Breath matches the scale of the building with gauze-like banners that run floor-to-ceiling, each bearing an ink stroke. Marking this entry with a subtle touch, they are particularly paradisiacal in the full afternoon and move gently in the flow of a welcome breeze that comes in from the water. The artist collects a series of painting events into single material instances of his underlying motivation to experience an instant of living. Although this seems overly ‘Zen’ to me, in this space, on this day, this is what the work achieves. I am reminded of my niece back in Wellington: experiencing ‘learning difficulties’, she has a unique way of understanding and looking at the world. As a young child, she would lift her finger and run it down the air in front of her, as if marking lines in the distance to denote what she found there. Picking up on her gesture, I have also sometimes done the same to mark out Wellington’s hills, thinking, as I am with Breath, about how we relate to such things, in terms of space.

Similarly well-placed, either side of the entry, are works by New Zealand artist Phil Dadson and Polish artists Aleksandra Janik and Magdelena Hlawacz. Stacked across wall and floor in one corner, Janik and Hlawacz’s Place: the Quest for the Quest collects reflective and light-making surfaces that play off each other in a kind of never-ending and elusive loop. It immediately brings to my mind a passage from Watermark - a prose collection by Joseph Brodsky that explores his relationship with Venice. He describes his sojourns as marked by reflections of reflections in a city that entices its visitors, yet secretly retreats, while they see themselves reflected over again.

Phil Dadson‘s Anatomia Sonora da Camera also carries light and reflections as he presents the meditative passage of his kayak gliding under Venice’s backwater bridges. It also carries out sound, as a beginning and backdrop to navigation of the Palazzo’s interior. Bringing the two sides of each bridge together, his journey makes water and bridge into a kind of stereoscopic lens, and the basis of a multifaceted, sometimes even kaleidoscopic, way of seeing as images merge, invert and play with orientation and direction. At the same time, he transforms the underside of bridges into resonance chambers, casting his own voice and the voices of others with soundclips including various religious chants, and a few bars of the always recognisable Maria Callas. The work is a rich kind of open air research. For me, it embodies a longing for water as a possible basis of respite and contemplation, away from the dehumanising crush for prescribed momentoes that characterises the tourist season and unfathomably, yet perhaps inevitably, has become an acceptable experience of the city.

Moving further in, a number of works continue to layer up this exhibition’s exploration of Venice. I enjoy Zambian artist Diek Grobler’s So much depends upon a stick in the mud, with its multiple small display screens that flash images of the lashed wharf piles that mark passage through Venice’s lagoon. Over and over, this essential form plays out a sculptural existence, the single frame is made a sequence, and time becomes ridiculously compressed. Nearby, Korean artist Yoo Joung Hye’s The Garden of Co-existence, presents 118 crocheted wire flowers to represent the 118 ‘islands’ lashed together to create Venice, and inspired by the past of lace making on the lagoon’s northern island of Burano. These are multiplied by reflection at ground-level with the use of a shiny, folded aluminium sheet, oddly creating the possibility of an intensely interior world where the craft of the hand remains and is amplified.

Isle of Dreams, presented by Finnish artists Anna-lea Kopperi and Heini Nieminen, is also tied to a historically significant lagoon island and its craft: the Murano of ‘Murano Glass’, that over centuries, has been an internationally renowned site and centre for the development of glass production. In one nearly uninhabited part of the island, Sacca San Maria, the discards of the island’s glass factories accumulate to create an ironically bejewelled wasteland and the first public site of this work. With 48 Venetian primary school children, they visit the area so that each child can search for their own small treasure of Murano glass. Along with each contributor’s treasure is a word they have written to capture something of their own dreams for the future. On one card I note the word ‘Scuola’ (school) and this touches me as a singular and grounded marker for a project that transforms the overlooked details of the everyday, while it also collects shards that (re)combine to make a work of art.

In relevant proximity, are two large 2D wall-based works that carry on a sense of the Palazzo’s scale and lead me down the monumental room of the Palazza. The first is Korean artist Song Dae Sup’s diptych Mud Flat, which moves intricate patterns and coloured pathways across paper’s surface, and the second, is Korean artist Kim Dong Young’s Embracing, which makes a richly material and subtly decorative use of (what I assume to be) locally-sourced lace.

Moving down towards the water of the Grand Canal, the sounds of the city’s water life move more to the fore, and the breeze can be felt against the skin. It is at this end of the Palazza that I again encounter A horse, a horse!, one of the works I glimpsed in its performance, as a projection, while in Schild’s tent. I loved the work when I saw it then, as a brief encounter with the beautifully absurd event of a noble but comic horse being floated through Venice, upright and proud in a Gondola, right past where I’m now standing. And I love the horse now, with its apparently articulated limbs, statuesque size, crafted polystyrene and pastel-coloured body, and equine smile. It is quite a character.

It is the work of the Quartair Group comprising Dutch artists Geeske Harting, Jessy Rahman, Pietertje van Splunter and Thom Vink, and it strikes me in the same way as they describe themselves: wilful, original, playful and flexible. And it is a ‘laugh out loud’ moment when I note the agile subject’s animation as Muybridge’s horse, displayed onscreen at its hoof-level. The horse, in general, is indeed a recurring and familiar symbol, not least in the history of Venice which was known for its four bronze horses, or Triumphal Quadriga. Once standing on the loggia of the Basilica San Marco, they were plundered as part of Napoleon’s campaign, and then returned to Venice, only to be more recently relegated indoors due to air pollution.

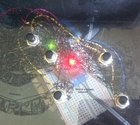

It is down by the water that I discover the work of another New Zealander: Data Processing System-a Sonic Cartography of Venice, by Charlotte Parallel, who lives and works in Dunedin. Like Phil Dadson, she creates a sounding of Venice, but with different tools and outcomes. Parallel has conducted open air research to create an intriguing work that translates site-specific recordings to unusual sonic landscapes, heard through interaction with a visual interface that well suits the nature of the work: screen printed maps on Pelican cases with push buttons and glowing lights. I feel like I am revisiting Jacopo de Barbari’s famous and beautiful sixteenth century woodprinted aerial view of Venice, in miniature, aided by a mechanical overlay that presents waterborne and ambient sounds. I become a kind of nomadic explorer and sonic voyeur, imagining Venice’s history and the way that might sound today.

Also by the water is Machines of Loving Grace by Dutch artist Harold de Bree and Italian artist Mike Watson. This is a performance-based work evidenced in a video that powerfully communicates a concept and aesthetic of anti-complicity. Adopting the look of methods they wish to subvert, they are dressed in threatening black military garb and appear on the jetty of the Pallazo, standing to attention, taking the city on as some sort of new order. They also appear in other strategic points around the city, as if engaged in surveillance, alongside footage of the people they found there. Also present in stacks within boxes is a listing document entitled Black Flag. This details the rights of citizens from all of the 89 participating countries of the Venice Biennale, upon arrest.

Tucked in an anteroom a little back from the water is one of my favourite works of the exhibition: Chilean, Switzerland-based, artist Enrique Muňoz Garcia’s documentary work, Tombola. The voices of the locals of the long and thin island of Pellestrina capture me. So does the way vignettes of interviews and stories string their lives together through the frame of the game Tombola, in which coloured counters, that look like multifarious Murano glass beads, are arranged on charts by women as numbers are called. Played in an empty school house, the game is an important part of the life of a community whose island protects Venice from the Adriatic, while its youth, and eventually its social structure, disappears. It’s the soundtrack that really brings this work to life, particularly the timbre and rough music of a drinking song I realise I have been hearing for a while. Once I have its source, and stop and watch, and translate it for myself, I am freely laughing at the joyful defiance and humour it embodies. Along with candid photographic portraits of some of its women, the entire work achieves an unexpected sense of spontaneous intimacy, as if we have passed the open door of a home and glimpsed the rich dynamics of the family gathered there.

Also in the anteroom is The Net by Korean artist Shin Yoo La. Along an ornate chaise longue, she has strung a net weighted with Murano-glass-like jewels in the form of rings and other objects. Better light and an angle with which to see the net’s folds and drapery would highlight the mysterious and evocative nature of the net itself. Nevertheless, it effectively fringes a video of the artist wearing and dragging the net around Venice-under the trinket laden colonnade of San Marco Square, through piazzas and along canals, it feels like the commercial weight of Venice itself, dragging itself along each Summer, while the details of its fabric and the way it moves eludes us.

On my way back through the Garden, I notice a work I didn’t see before-French artist, Christophe Doucet’s The Daphne Crown. The now late afternoon sun catches the glass laurel crown he has gifted to the dilapidated, and almost overgrown, statue of Daphne. As Doucet transforms her moment of transformation into a laurel tree, he claims the role of sculptor and maker, gathering light around a historic and forgotten subject and object. His is a small transformation of the myth in stasis. It seems a fitting work with which to end my time with Jump into the Unknown, in Venice.

Jodie Dalgleish

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.