John Hurrell – 9 July, 2015

Looking at Newby's assorted groups of ceramic objects laid out on the pallets, apart from an obvious love of texture, muted mottled colour and twisted gnarled forms, we see - as with Paul in her poem - a focus on classification. Newby is interested in the structures of organisation and sorting, a taxonomic mindset that in this country can be traced to the eighties, especially the museological, cupboard sculptures of Christine Hellyar and the large paper grid work, Vademecum, of Julia Morison.

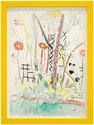

This exhibition juxtaposes the short films and delicate drawings of the late Joanna Margaret Paul with the colourful ceramics and ‘casual’ installations of Walters Prize winner Kate Newby - while tangentially referencing the interest both artists have (or had) with language. Paul is represented by four short films (1971 -1982) in the small gallery, with five framed pencil, pastel, watercolour or gouache drawings coming from the 80s and 90s, in the larger one, while nearby the Newby works - glazed ceramic shards and objects or found metal items - are laid out in clusters or lines on four differently sized combinations of flat wooden pallet.

Paul‘s very short (3-4 minute long) films - a sort of home movie where, instead of family members, we see ordinary objects (part of a domestic environment), ordinary sources of natural energy (blowing wind, dripping or flowing water), or ordinary vistas (the stark concrete forms of a motorway overpass, clumps of flowers, a section of wirenetting fencing, the choppy sea and abrupt cliff forms of Otago peninsula filmed out a bus window) - emphasise strange angles or activity on the edge of the frame, and a familiar household environs. Paul seems revolted by the exceptional or exotic, taking repeated pleasure in the prosaic and normal, enjoying their simplicity and presence.

Her pencil and wash drawings reflect this interest in what is close at hand as part of day to day existence. Sometimes though there are references to other writers or other artists, the world of intellectual debate pondered during daily tasks. (These published notes show her complex ruminations on poetic thought (1)). The White Hotel suggests an internal monologue alluding to the famous novel by the poet and translator, D. M Thomas.

In Paul‘s poem, the Course, published in the Auckland journal PARALLAX (Vol.1, No.2) in Summer 1983, she describes some ‘low lying naked succulents’ in the marsh:

zone; SALICORN AUSTRALIS neutral, but now its long

smooth thallus is pink to pinkish grey, & among the

little dark round leaves of SAMULUS REPENS, SELLIERA

RADICANS thews flash fleshy green; in ponds ancient

snails are grey then pink now russet brown; the

men have stopped talking & stoop very quickly

intently picking up snails peculiar to ARAMOANA

3 mm long soft narrow brownish hidden among roots of

LOCHNOGROSTIS LYALLI & LEPTOCARPUS SIMILIS (p.208)

Looking at Newby‘s assorted groups of ceramic objects laid out on the pallets, apart from an obvious love of texture, muted mottled colour and twisted gnarled forms, we see - as with Paul in her poem - a focus on classification. Newby is interested in the structures of organisation and sorting, a taxonomic mindset that in this country can be traced to the eighties, especially the museological, cupboard sculptures of Christine Hellyar and the large paper grid work, Vademecum, of Julia Morison. She likes to make categories, means of sorting out forms.

In one work, All parts. All of the time, Newby has eight different groups - ceramic items and found metal elements - one in a latticed box, presented with handwritten labels on strips of paper placed underneath. The eight ‘scruffy’ labels are deliberately indifferent to the categorisation, for apart from the last one their sentiments are totally independent of the objects above them. They go like this: Love Rocks; Legs; I’m embaressed [sic] because Lou Reed doesn’t know me; It is not that hard to leave someone; Feelings; Make it bigger and more interesting; Incredible feeling [written in marker] dish washing liquid, milk, kitchen cloths [written in biro]; skim stones formed by clapping hands.

Of the four ‘floor’ works, the biggest work is on knot-holed, date-stamped plywood pallets and is especially engrossing in its fine detail and sprawling size. The one with labels is on a saffron-stained cotton cloth on a pallet, another of cast bronze, brass and silver pieces has them placed on brown fabric mat on a red painted cardboard base on a pallet, and the fourth (just as far as my eyes can see) with delicate, fragile pale units that bear stamped impressions, has a painted cardboard base of blue on a pallet. They are deceptively complex. The ceramics of the big work (Casualness: it’s not about what it looks like it’s about what it does, 2014-2015) were made in Auckland. The others were produced in New York, where she currently lives.

These artists make a terrific combination when their works are alongside each other, both being interested in subject matters and materials that are close at hand. With Paul, the transferred film sometimes has a blurry or grainy texture (hovering over the recorded image) that comes from the onset of cellulose corrosion. This ironically makes her more matching, while with Newby, her pitted pocked textures often can only be appreciated by your getting down on your knees to scrutinise closely; ocular and knee-joint discomfort going together. A fascinating show.

John Hurrell

(1). See also Joanna Paul, ‘Landscape as Text: The Literacy of Wayne Barrar,’ in Now See Hear: Art, language and translation, published by VUP, 1990, edited by ian Wedde and Gregory Burke, pp 80-84.

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.