Sonja van Kerkhoff – 28 September, 2015

Hunter's photography, often in series of images, bridges the genres of moving image and the single frame, forcing the viewer to choose to read the work as a total composition (the object) or to follow the flow (the story sequence). However Hunter's narratives often disrupt the flow, because the image, form and story break the spell of the suspension of disbelief. The artifice, or overkill, is the point. The image takes us in and then pushes us back.

In November 2014, the Richard Saltoun Gallery in London hosted a premiere screening of the 12 minute film, Alexis Hunter: Approach to Fear. The film slides between the conceptual edge of her photographic work; her witty drawings; comments from Lynda Morris (Professor of Curation and Art History, Norwich University), Griselda Pollock (Professor of Social & Critical Histories of Art, Leeds University) Cristian Albu (Post-War & Contemporary Art Specialist, Christie’s) and Richard Saltoun (Richard Saltoun Gallery) and Hunter’s own warm and provocative interjections, which she wrote, having lost the power of speech in early 2013, due to motor neuron disease which killed her in early 2014, at age 65.

The film was directed by Lindsey Dryden (Little By Little Films, UK) who was introduced to Alexis Hunter by cinematographer and executive producer, Nina Kellgren. Dryden’s interviews involved Alexis writing on a whiteboard or tablet, often with Nina present. Alexis Hunter’ s presence in this film - also in the archival footage - make this multiple mode film a true homage to her work, because ‘the female presence’ is the overt feminist stance of her oeuvre.

The nature of the art world means that the conceptual and the expressive generally don’t fit the same gallery circuit. In fact Alexis’ advice to any artist was to stick to presenting one mode if you want success. She continued to paint expressively until she was unable to hold a brush in her hand, as well as exhibiting her paintings, often with the outspoken anti-conceptual “Stuckists,” while simultaneously showing other work in other circuits. Provocation and taking oppositional stances were her artistic approaches, a method that was breathtakingly honest. Her political stance was not only deeply felt but also intellectually crafted, and multi-moded.

These days it is not unusual for an artist to work across media or to switch media, but galleries and the public often see a consistent style as a sign of professionalism. I will focus on her photographic work here, because it would take a book to tackle her rich expressive paintings and dry wit performance works, but all of her work was informed by taking away the ‘fear’ by being overt about the very thing feared most: feminism. Feminism is a fearful thing, and not just for men, because it unsettles everything we have learned from history and in particular how we look - the gaze.

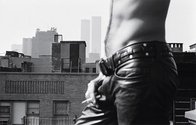

Alexis Hunter took how we look at the human form by the horns and threw it back at us. The man’s torso in the photograph Object Paintings is either eye candy or a confrontational reminder of the objectification of the female body. Ironically - post 9/11 - the centrally located towers tend to divert the gaze past the out of focus man’s torso, but the composition still works as intended. The eye runs around the hips to the sharply focussed grid of architectural contours. The man is surface and form.

Initially this man’s torso was presented as a photo-realistic painting at the end of a sequence of six on the themes of objectification and form and, therefore, the gaze. Here this image reads more like a billboard, underlining the inversion of expectations: a larger than life male body as seductive object. She shows details on headless figures - a tattoo, boot, or belt, to overtly objectify the subjects, yet the camera angle and intimacy maintain an involved space for the viewer. As Lippard notes, quoting Judith Williamson’s analysis of advertising: “we are drawn to fill that gap so that we become both listener and speaker, subject and object” (1)

In the same 1981 essay, Lippard wrote of Alexis Hunter’s motives for this series:

She used a narrative, commercial-looking style because she hoped through its banality to make her work accessible to the 80% of the British population who watches nightly television. Her remedy was somewhat homeopathic. By entertaining her audience, or at least encouraging it to participate in this illusion, she hoped to make some clichés transparent, to tell some truths about the lies that photography tells. (2)

Hunter’s photography, often in series of images, bridges the genres of moving image and the single frame, forcing the viewer to choose to read the work as a total composition (the object) or to follow the flow (the story sequence). However Hunter’s narratives often disrupt the flow, because the image, form and story break the spell of the suspension of disbelief. The artifice, or overkill, is the point. The image takes us in and then pushes us back. Hands, if female, hers, are too well manicured for the job, yet they also mimic the types of hands in glossy magazine advertisements. That we would expect these hands to be showing us some form of cleaning product is salt she is rubbing into the wound.

The hand in the image, Approach to Fear III: Taboo demystify here is not cleaning, it seems to be feeling up the machine. The overkill - the step by step, not quite frame by frame - of a hand and greasy motor parts, reads like an instructional manual. A lot of conceptual photography (for example, John Hilliard’s sequential photographs) has this mannered aspect but Hunter’s images are also intimate and visceral. The camera view is the artist’s and ours. These could be our hands. The emotive power in the imagery forces the political to be read as a personal story, by the feminist hand.

So the ‘fear’ in the titles of her works, is not so much about getting our lady hands dirty or being in a man’s world, but about making an overt statement. These titles make the overkill more so. The photographs slide between voyeurism (as used in advertising) and the staged, and the fear for the art viewer could lie in not knowing how to read them. Hunter’s oppositional stance was intentional. A lot of feminist art of the time was focussed on the female body in a woman’s world and it would not be too sweeping to say that Hunter’s world focussed on confrontations in all worlds. Her 1978 series The Marxist’s Wife (still does the housework) makes fun of socialist theory (and academia in general) as much as it is a reminder that housewives don’t have retirement plans. In Approach to Fear III: Taboo-Demystify these hands are dirtied/marked/scarred having been in a man’s world. The finger accessories make the point that the artist is not complicit. She is a feminist and she is telling you this, overtly.

A lot of her imagery has a biographical starting point, which she sometimes hammers to break another taboo: the fear of the involved subjective artist. Hunter’s distinction, as compared to artists such as Mary Kelly, Barbara Kruger, or Mona Hautom who underline the personal-political in their work, is in her crossing of class lines. The language is unabashed working class. In the work Dialogue with a Rapist the text is plain and direct and the imagery a power play between the hands of the protagonists. Everything is pared back. It is the empty street and the hands and the knife and the banal values behind the crude dialogue. Alexis was not afraid to push buttons.

At the end, when Alexis was severely debilitated, Lindsey Dryden writes:

Alexis was clear about what she wanted to discuss and cover in our interviews, and one of my favourite afternoons involved her and I going through old films she was in, and Alexis telling me which parts of her contribution she liked, which were important for our film, and which she thought were a bit ridiculous. It was a lot of fun, and also a chance to witness her reflection on older statements she’d made. Much of what she said in those films was pretty prophetic, had remained her perspective for all of her career, and was relevant to the feminism we were now discussing.

We tried to keep our shoots and meetings limited in length to preserve Alexis’s energy: One or two hours was often a good time, and towards the end of the filming process these meetings and shoots got shorter. Alexis was very communicative about how much she could do, and once she felt it was time to stop working it was important we wrap and head off quickly. At the same time, she was absolutely full of energy and drive, and was working constantly, with us on the film, on press and writing, and on her archive and estate. A quiet whirlwind. (3)

Sonja van Kerkhoff

(1) Judith Williamson, Decoding Advertisements; Ideology and Meaning in Advertising, London, 1981, quoted in the essay ‘Hands On,’ in the catalogue, Alexis Hunter, Photographic Narrative Sequences, 1981, Edward Totah Gallery, London, and in the 2006 catalogue, Alexis Hunter: Radical Feminism in the 1970s.)

(2) ibid.

(3) email to the author, 2 April 2015.

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.