John Hurrell – 9 August, 2016

Akomfrah's spectacularly beautiful - but relentlessly disturbing - densely packed film deals with humankind's savagery towards other humans and other animals, usually within the domain of the sea. Incessant butchery and casual indifference are the dominant themes, repeated in alternative versions on the three aligned screens.

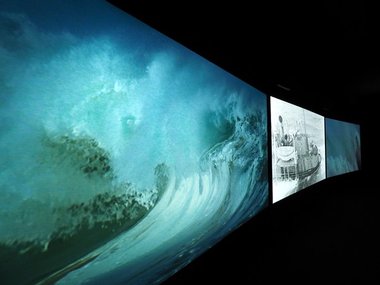

In this carefully fitted out version of CoCA’s Mair Gallery - the large high space at the top of the stairs - carpet has been laid over the polished concrete floor, baffles and speakers installed for surround sound, and three large screens positioned in a row, transforming it into providing an aural/visual experience that is comparatively intimate. The occasion is Vertigo Sea, a recent film installation from the distinguished British/Ghanaian filmmaker John Akomfrah, famous for his inventive use of archival film footage, examination of immigration issues and various philosophical debates around post-colonialism, and love of the recorded spoken word and English literature.

Akomfrah’s spectacularly beautiful - but relentlessly disturbing - densely packed film deals with humankind’s savagery towards other humans and other animals, usually within the domain of the sea. Incessant butchery (whales, polar bears, elephants, stripped Argentinean dissidents thrown alive out of planes over the Atlantic, victims of atomic bomb radiation, British slave ships heaving 147 prisoners - dying of thirst - into the sea to claim insurance) and casual indifference (drowning refugees, desperate boatpeople, sulphur miners working in toxic fumes) are the dominant themes, repeated in alternative versions on the three aligned screens. News reports provide the occasional voiceover, or quotations from say, Melville, (Heathcote) Williams, Woolf or Milton.

Along with archival film, and acted out scenarios, Akomfrah uses a lot of gorgeous film from the BBC’s Natural History Unit, including aerial shots of thousands of seabirds and dolphins. Dazzling colour in sunlight drenched nautical imagery is juxtaposed with the flickering smoky greys of historical documentation; sizzling chroma paradoxically placed within a mood of deep disgust and despair.

Mixed in with the imagery are various allusions to ecosystems and the holistic health of the planet; symbols such as whirling Tibetan prayer wheels, or sand dunes covered with ticking clocks. One regularly repeated motif is a colonial couple sitting on the beach looking out to sea, oblivious of impending environmental changes. Nearby is a dead deer suspended inverted. In other scenes, a standing red-coated gentleman anxiously holds an old fashioned clock.

Now and then natural creatures are presented en masse to become something beyond themselves: metaphors for human characteristics: feeding eels and starfish become associated with frenzied human greed; shoals of jellyfish are linked to pollution-created toxicity, clouds of monarch butterflies for migrating peoples.

Documentation of the hunting and carving up of whales plays a large part role in this film, and so with the convenient collection of trypots and blubber-cutting tools (from some of the five local whaling station sites in Banks Peninsula) in the nearby Canterbury Museum, the narrative content of this installation (commissioned for the British Pavilion at last year’s Venice Biennale) has a lot of resonance for history-conscious Cantabrians. CoCA Director Paula Orrell’s invitation to Akomfrah is a brilliant strategy to draw in Christchurch residents.

What is fascinating about the presentation is Akomfrah’s formal control with the visual components. The editing (image choice and timing) is very tight, especially with the use of balanced symmetry and morphological echoes on the three screens. Usually contemporary coloured filmic material is on the outer rectangles and much older grey toned archival film in the centre.

And there is a calculated poetry to Akomfrah‘s thinking. While he is extraordinarily erudite and scholarly, and superbly articulate, he also embraces a sly looseness and slipperiness within his image juxtapositions which are rich in associations. Heard and read language slides around and is malleable for reuse within different contexts: vertigo becomes vertical, sea becomes see. The work is preoccupied with ethics, history and morality, but is not finger-wagging. He gives you plenty of space to form your own conclusions. Surrounded by sensuality and beauty mingled with appalling horror, you are not pressured into following ‘correct’ channels but free to discover; to plunge into chance-encountered depths at will.

John Hurrell

Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.