John Hurrell – 7 January, 2017

Probably the most successful project here is A Library to Scale (2006), a show that looks at the collection of scrapbooks obsessively put together by Frederick Butler (1904-1982) now kept by Puke Ariki in New Plymouth. The 3500 volumes are covered by wallpaper and contain pasted-in clippings on a vast array of subjects about Taranaki life, taken from very old newspapers, some printed long before Butler was born.

Auckland

Ann Shelton

Dark Matter

Curated by Zara Stanhope

26 November 2016 - 17 April 2017

University lecturer and artist Ann Shelton is well known for her more recent large, thematically varied photographs that often feature inversion, and her much earlier documentation of the social life of Auckland’s K’ Rd region in the mid nineties. This institutional survey features samples from fourteen exhibitions that she presented from 1995 to 2016, all of which have been carefully culled to fit the spatial limitations of the five (comparatively small) Auckland Art Gallery rooms. AAG’s colourfully prepared walls (with their unusual synthetic / chromatic blending) are a distinctive foil for some of Shelton’s more prosaic architectural subject matter.

The conceptual content of these mini-shows varies greatly, but often it is about location - particular sites where horrendous crimes or violent incidents have occurred, or places with a palpable link to some person widely considered evil. Or else Shelton is interested in architectural genres: particular types of institutional or functional building: their exteriors and interiors; external cladding and internal methods of decoration.

In three projects Shelton uses a system of doubling where images are repeated at exactly the same size, but either inverted vertically and mirror-reversed, or mirror-reversed on a horizontal axis. The first format applies to the In a Forest (2005) series, where saplings given to medal winners at the 1936 Munich Olympics by the Nazi hosts were planted in various locations around the world - these photos are inverted and shuffled around - and also Once More from the Street (2004), images of the buildings of Lake Alice Hospital, not shuffled but kept in pairs. The second applies to famous crime scenes (Public Places) where you have to guess which half of the horizontally mirroring pair is factually accurate.

With Public Places (2001-3), the juxtaposition of the two options of ‘reality’ is particularly clever. You can either do some research later in order to make a decision, or you can just enjoy the teasing quandary for itself. With Once More from the Street, you tend to think about inversions and whether mental illness - the focus of the hospital - can be an upside down version of reality. (Here the trope, I think, seems glib and far too simplistic.) And looking at In a Forest, the random inversion placement, while suggesting a community of evil (a group espousing topsy-turvy values), seem overworked. To me, Shelton should have kept things understated, and limited herself to orthodox documentation of the thirteen oak trees. However the stories she has uncovered about the plants and their athlete owners make engrossing reading.

One of the other exhibitions, Room Room (2008), looks at the assorted living spaces of Phoenix Block, part of the Salvation Army Drug and Rehabilitation Centre on Rotorua Island in the Hauraki Gulf. Her images of basic bed and cupboard furniture (with curtains) are in a tondo format and thus distort the architecture of the rudimentary boxlike room. The repeated circular shapes suggest a voyeuristic peephole sensibility whilst also distorting the vertical lines and angles, creating a hallucinatory ambience.

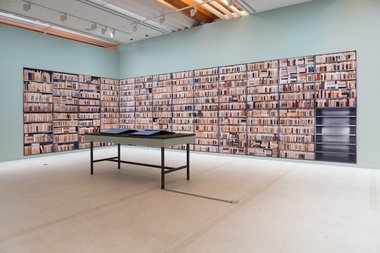

Probably the most successful project here is A Library to Scale (2006), a show that looks at the collection of scrapbooks obsessively put together by Frederick Butler (1904-1982) now kept by Puke Ariki in New Plymouth. The 3500 volumes are covered by wallpaper and contain pasted-in clippings on a vast array of subjects about Taranaki life, taken from very old newspapers, some printed long before Butler was born. Not kept publicly displayed on shelves, the outward spines of these eccentric historical archives are presented by Shelton in 26 butted together photographs that traverse a corner, cumulatively and slowly created by photographing different groups of books repeatedly in a single metal bookcase.

The cuttings stop in the mid sixties, while most are from the mid-fifties. Here are some of the subjects: births and marriages, body building, camera club, character types, crime, education, errors, families, hotels, Maori, Maori pa, nudism, office, petrol, prices, remedies, Samuel Butler, sea shells, shipping, Taranaki history, war, watersiders and weather.

In this work Shelton has created a visual fiction of cohesive shelving, and a sort of running (handwritten) text: names, dates and book numbers that you ponder as your eye crosses horizontally over the crammed together, oddly decorative, spines. Nearby, in the middle of the room, is a photographic presentation of sample pages on four touch screens. Most are newspaper cuttings but sometimes Butler has copied out articles by hand. The whole project is about somebody obsessed with time; an insider’s view of changing culture, mingled with a compulsive drive to make books that can be indexed in the hope that future generations will find them valuable.

Shelton’s most recent project, Jane Says, mixes various medicinal plants with ceramics and an Ikebana-style presentation to focus on women’s use of plants for fertility or birth control. Through their use over the centuries, the nine photographed plants have acquired symbolism in order to here represent certain female stereotypes. For example we have: The Comfort Woman (Stock), The Courtesan (Poroporo), The Child Bride (Thistle), The Mermaid (Wormwood), The Ingénue (Yarrow), The Vixen (Ginger). These stereotypes probably can’t be identified without reading the labels, and Shelton provides a poster full of informative quotes about the botanical references. Yet I have reservations.

With these co-ordinated clusters of signifiers and correlating referents, we see an old fashioned conservative (pre-modern) style of symbolism that raises questions about the aim of contemporary art. One person might argue the view (that’s very popular today) that art’s function should be generate political meaning and attempt to improve the world, while another might plea that the method of the meaning’s manufacture is the crucial aspect, not the viewer’s interpretation.

I would like to suggest that neither is accurate, though the latter is the more valuable of the two. The issue is about the manufacture of new production processes of meaning, ie. methods of creating new techniques of conveying sense. It is about contesting orthodox structural layerings within various art systems, not perpetuating a well worn interpretative method. For these reasons I see Shelton’s construction of meaning in a project such as Jane Says as over-determined and moving backwards, while in contrast the mirroring of Public Places and use of a single bookcase in A Library to Scale introduce valuable inflections about art and artifice within any viewer’s consideration of her assembled photographs.

John Hurrell

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.