Warren Feeney – 1 February, 2017

More critical, however, is the lack of appropriated evidence of painting as a process of exploration, where the artist is prepared to make mistakes in the act of discovery about their subjects, ideas and potential of their materials. This is not to suggest that Carlin needed to take such fundamental principles of modernism too seriously, but at the very least, she could have included something of the customs that reveal the sense of chaos in Hodgkin's' art.

Dunedin

Kirstin Carlin and Frances Hodgkins

Through the Trees

Curated by Lucy Hammonds

30 September 2016 - 22 January 2017

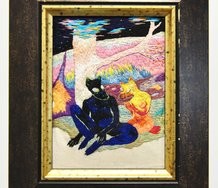

Through the Trees brings together three paintings by Frances Hodgkins from 1935 to 1943 and twelve recent paintings by Kirstin Carlin in the Dunedin Public Art Gallery’s designated exhibition space for Hodgkins’ work.

The decision to pair the work of both artists in a single exhibition seems almost inevitable. In the Auckland Art Gallery’s Necessary Distraction: A Painting Show, (November 2015 - March 2016) Carlin was represented by a series of works titled Pleasure Garden, referencing Hodgkins’ infamous Neo-Romantic painting from 1932, gifted to Christchurch’s public gallery in 1951.

Through the Trees singles out Neo-Romanticism’s reconciliation of figuration and abstraction in paintings by Hodgkins that, in the 1930s and 40s shared much in common with artists like John Piper and Graham Sutherland, reconsidering European modernism and abstraction in works that stood their ground by arguing in favour of figurative images.

Senior to many of the English avant-garde who admired her painting, Hodgkins’ work in the early 1930s anticipated where English art was heading. Advocates for pure abstraction like Piper and Sutherland reassessed its relevance to their practice, culminating in the publication of Piper’s essay, ‘Lost. A valuable Object,’ (1937). After a decade of abstraction, Piper rallied for a return to representation; ‘to what he called with beguiling simplicity ‘the trees in the field.’ When he described some of the objects occupying his own imagination, however, they were fantastic agglomerations of ideas…. it was an unusually elastic idea of modernity, but by the late 1930s it could claim a great deal of support (1).

For British artists the idea of alternative ways in which modernism and abstraction could flourish together, beyond the notion that its centre was in Paris with Picasso and Braque, was more than a nationalistic call to arms. Rather, in arguing that figuration could sustain its presence in the work of the best of the English avant-garde, they initiated a response that would eventually see Great Britain gain international prominence with the emergence of ‘Britart,’ and artists like Damien Hirst and Sarah Lucas in the 1990s (2).

This was quite different from New Zealand, where modernism in the 1950s, rather than consider alternative options to Paris and New York, rejected Neo-Romantic influences. The anthropomorphic landscapes of Eric Lee-Johnson represented the enduring, and by then, unfashionable influence of Britain.

This came to an end when English museum manager and curator, Peter Tomory was appointed director of the Auckland City Art Gallery in 1956. In an essay in Landfall in 1958 he highlighted the perceived problems with the illustrative in serious painting, arguing it compromised the experience of viewing. Lee-Johnson reputation’s as a credible contemporary painter was over (momentarily at least), with Tomory’s claim validated by the artists he described as picture-makers: Rita Angus, Colin McCahon and M. T. Woollaston. Yet, the illustrative and figurative priorities of Hodgkins’ paintings escaped such criticism, no doubt because of her reputation as a pioneering modernist, highly visible in public throughout the nation-wide controversy over The Pleasure Garden from 1947 to 1951.

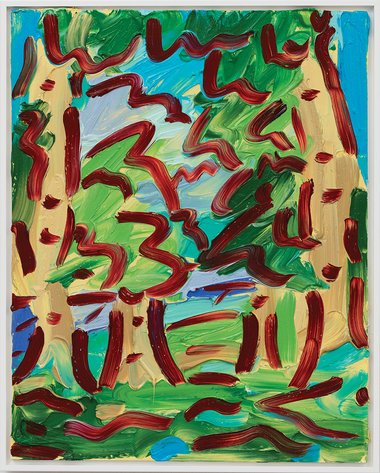

Carlin’s paintings in Through the Trees, like those in the Auckland Gallery’s Necessary Distraction positon her response to Hodgkins’ paintings as decorative, playful and accessible in the abstraction of their subjects. In their attention to style, Carlin nails the legacy of Hodgkins’ painting in New Zealand’s art history. A tentative ‘radicalism’ (one well-suited to a country far from Europe still learning about abstraction) with Hodgkins as a kind of John the Baptist, pioneering by proxy the modern movement in post-war New Zealand. Carlin’s paintings embody the spirit of the myths and constructed realities about Hodgkins’ life and art as seen as an expatriate artist.

Yet Carlin is also specific about according priority in her work to the particular formal conventions of Hodgkins paintings, encouraging a conscious reconsideration of Neo-Romantic painting. She works her way through a checklist: the framing compositional device of trees; the definition of forms in black or dark outlines; an emphasis upon the simplification of form and detail; a lyricism in the treatment of line and an emphasis on decorative colour harmonies, evoking notions of peace of mind or joy. In general there is a preference for joyfulness, predominantly due to her appropriation of the blues, reds, greens and yellows in Hodgkins’ Mill House (1935).

However, the experience of Carlin’s paintings as a ‘construct’ or critique of Hodgkins’ painterly sensibility and skills as informed picture maker, never quite happens, in spite of the anticipation and accompanying promises of the exhibition catalogue. Lucy Hammonds describes Carlin’s summary description of Hodgkins’ work as a ‘painterly shorthand that riffs off the elements of a composition.’ This seems far too generous. I had no expectations of Carlin pedantically making use of the same materials as Hodgkins - that is gouache on paper instead of her choice of oil on canvas - yet, there are problems with Carlin’s pastiche of Hodgkins’ paintings. Oil on canvas places these landscapes closer to early Matisse or Derain - or even Braque’s early Cubist landscapes. In doing so, they become a tentative and abridged take on the ‘look’ of Neo-Romantic landscapes.

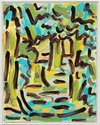

More critical, however, is the lack of appropriated evidence of painting as a process of exploration, where the artist is prepared to make mistakes in the act of discovery about their subjects, ideas and potential of their materials. This is not to suggest that Carlin needed to take such fundamental principles of modernism too seriously, but at the very least, she could have included something of the customs that reveal the sense of chaos in Hodgkin’s‘ art. The artist in the act of changing her mind, is evident in works like Green Valley, Carmarthenshire (1942) with its inconsistency of paint application; thickly applied gouache and diluted washes of colour; exposed paper untouched by the artist’s brush; and an image that continually appears to oscillate between dissipating and reasserting itself as landscape.

Of course, as Hammonds states, Carlin is not conceiving and realising paintings, she is making ‘paintings about paintings.’ And therein resides the problem. Although claims may be made about her celebration and interrogation of the ‘artifice and materiality of the painted image,’ in Through the Trees it is the gnarly Neo-Romantic paintings of Hodgkin’s that are doing all the interrogating, calling Carlin’s painting to account for itself and its reasons for being.

American art critic Barry Schwabsky argues that the most vital and engaging painting today is coming from artists concerned ‘with a physical involvement in the image’ - a blurring or morphing of the image and materials into something revealing and unique, that could only be painting. Hodgkins’ paintings sustain the kind of experience that Schwabsky describes. In Through the Trees, her landscapes feel like we are reading and experiencing the complete dissertation, while Carlin’s, too often, adopt the role of an accompanying footnote.

Warren Feeney

(1) Alexandra Harris, Romantic Moderns: English Writers, Artists and the Imagination from Virginia Wolf to John Piper, London: Thames & Hudson, 2010, pp. 36 - 37.

(2) James Hyman, The Battle for Realism: Figurative Art in Britain During the Cold War 1945 - 1960, New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2001, pp.1- 9.

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.