Ralph Paine – 9 November, 2017

When considered a modality of a demonic distribution it becomes evident that art can have no proper place, no patrimony, no fixed institution or identity. In this sense, what “acts” in art is a “plastic, anarchic, nomadic principle” that precedes actual artworks. Spurred by this principle, artworks leap. They leap over barriers and walls. Over borders and boundaries, limits and termini—and this even when seemingly crouched in profound stillness and silence: a watercolour, a novel …

Recently, Lana Lopesi expressed contempt for Francis Upritchard, accusing her of theft, misogyny and racism and of receiving unwarranted dispensation for her art. By way of rejoinder, I present the following.

…………..

In inquisitorial times, how best to speak in defence of those intimate strangers whom we adore? Of those who have created the world afresh and cast us adrift in its lightness, its currents and eddies, its storms? They are famous artists, musicians, poets … And us? What possible alliance might we offer these grand midwives of our being new born?

Thus our complex dilemma, dilemma of the fan …

It is said that the fan has precursors—spectators in ancient arenas, eighteenth century fanaticks, the maniacs of 60s pop—and an etymological link to demons and temples (fanum). (1) Perhaps then the fan recognises the self to be a demon (daimôn, daemon), or at least to be demonised by others, a recognition that will call forth the world as shared hallucination. In Difference and Repetition Gilles Deleuze describes this type of sharing as “an errant and even ‘delirious’ distribution,” one in which “things and beings” are not distributed “according to the requirements of representation.” “Such a distribution,” he says, “is demonic not divine, since it is a peculiarity of demons to operate in the intervals between the gods’ fields of action, as it is to leap over the barriers or the enclosures, thereby confounding the boundaries between properties.” (2)

Although today most often invoked as minor gods or evil spirits, in contradistinction Deleuze is tracing here a semantic thread connecting demons to an esoteric and far more indeterminate zone located somewhere between gods and mortals and thus he envisages demons as virtual forces, guiding forces, drives, tendencies, probe heads, simulacra. Doubtless it was Christianity which made a daimôn or daemon an evil being and impressed upon the names the significance which “demon” now has in common usage. Nonetheless, a fruitful equivocation of meaning remains within and when translating between European languages. (3)

When considered a modality of a demonic distribution it becomes evident that art can have no proper place, no patrimony, no fixed institution or identity. In this sense, what “acts” in art is a “plastic, anarchic, nomadic principle” that precedes actual artworks. (4) Spurred by this principle, artworks leap. They leap over barriers and walls. Over borders and boundaries, limits and termini—and this even when seemingly crouched in profound stillness and silence: a watercolour, a novel …

Deleuze distinguishes a nomadic type of distribution from a “sedentary” one. A sedentary distribution, he says, “proceeds by fixed and proportional determinations which may be assimilated to ‘properties’ or limited territories within representation.” Here, each god “has his domain, his category, his attributes, and all distribute limits and lots to mortals in accordance with destiny.” (5) Here, that which is distributed is space itself, and all “things and beings” allocated a proper place, a fixed identity, divided up according to a faculty of judgement dependent on transcendent measure. Art as spurred by its nomadic principle is captured and overcoded here, captured and overcoded to become part of a collective principle of administration and control wherein model-copy resemblances proliferate.

Without Deleuze stating it explicitly, what may be gleaned from Difference and Repetition is a way of forming the distinction between ethics and morality. In this we will speak of ethics in the manner of a nomadic distribution, and morality in that of a sedentary one. Hence: ethics thinks via immanence, morality via transcendence; ethics is a minor tradition, morality a major tradition; ethics consists of facilitative procedures or enabling guidelines, morality of constraining rules and limits or “thou shalt nots”; ethics makes evaluations according to life situations or “modes of existence” i.e. if we live like this then it follows that we will speak, act, and think in a certain way (either good, dignified, joyful or bad, base, sad), whereas morality makes judgements according to a pre-given order or set of laws i.e. this is always good, that is always evil.

It follows that an ethical critique of moralists will go something like this: “Given your transcendent laws imposed by force, all that the human will ever consist of is slavery and criminality, guilt and resentment, and all the behaviours that result.” On the other hand, a moral critique of ethicists will go something like this: “You are atheists, you promote nihilism and chaos. How can everything be socially relative or subjective? We can’t live in an ‘anything goes’ world. We can’t live outside the law. You are anarchists!”

Doubtless the contemporary art world comprises de facto mixes of nomadic and sedentary space. While sedentary space is constantly overcoding and traversing nomadic space, fixing boundaries, allocating and managing identities and resemblances, sedentary space is constantly being reversed, decoded back into nomadic space. In the first case, the art world organises even the demonic; in the second, the demonic gains and grows. Thus within any given mix the two spaces will communicate with each other in different ways and therefore assume dissimilarly hybridised forms. (6)

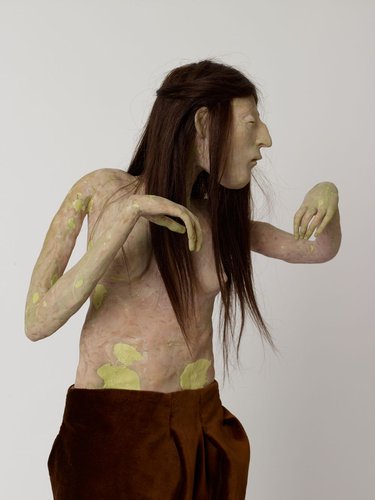

When Francis Upritchard says of her figures and objects that “they’re very inaccurate—decorative rather than spiritual,” that “they’re meaningless, rather than full of the power of real taonga, and they have no mana” (7) she wants to render them morally “inoperative.” (8) Or, said the other way round, she wants her art to operate via the “as not”: as not model-copy resemblance, as not religious, as not authoritative, as not moral. But rather than exodus or escape, what she desires is deactivation from within. Upritchard’s invocation clearly signals that she is attentive to the reality that all attempts will be made by institutions, curators, collectors, journalists, etc. to overcode her work as representative, spiritual, authoritative, moral. It’s as if she is saying, “Sure, my figures and objects abide within a sedentary distribution but I don’t regard them as terms, subjects, or perhaps even ‘works’ of that distribution.” Uprichard’s invocation thus suggests an ethical spin.

Not that her figures and objects call for the spin. A name is all that’s minimally required for us to get it that Upritchard presents—singular, dual, collective—”modes of existence”: Giver, Taker, Hannah, Tourist, Jockey, Sun Worshiper, Mandrake, Echo Chamber, Land, Jealous Saboteurs … Together, each name and each artwork (or group of artworks) “is also always a style” and “not at all something personal, but the invention of a possibility of life … It is an intensive mode and not a personal subject.” (9) Thus, Upritchard’s formula à la Deleuze: aesthetics = mannerism = ethics = contemplation of potential (ways of life) = “the Other as the expression of a possible world.” (10) For Upritchard, the Other is no one but rather a “plastic, anarchic, nomadic principle” that constitutes the field of perception for her art. The Other is the very possibility that there may be figures and objects and paintings at all, and that we may adopt a point of view on them. In this regard, Jealous Saboteurs (Upritchard’s complete oeuvre, in fact) constitutes an indigenous “plane of immanence” populated by conceptual figures and objects: caravan, troupe, clan, cavalcade, trading party, commune, ensemble, company … A posse of “floating weeds”—to invoke Ozu’s 1959 film title—and their magical kit, products and paraphernalia: an entire “image of thought.”

In our view, this image of thought is enacted via simulacra rather than copy-model resemblances or the ideal notions of identity and representation: “simulacra are precisely demonic images, stripped of resemblance.” (11) Neither degraded copies nor plundered icons, Upritchard’s simulacra are both “constituted by differences” and relate to each other “through differences of differences.” (12) Or, if her simulacra do refer to a model, the model is always already a possibility of the Other and thus a non-model or potential difference-to-come, and not a model of the Same. Accordingly, the figures and objects populating Upritchard’s remarkable plane of immanence—inclusive of their gestures, clothing, motifs, decoration, colour, etc.—cannot have been stolen. Rather, they have been reciprocally traded, given and taken along the rainbowed curve of a restless and ethical leap. Given and taken, that is to say, through a suspension of the Law.

Ralph Paine

(1) On “fanaticks” and fanaticisms of all stripes and colour see Alberto Toscano, Fanaticism: On the Uses of an Idea, London & New York: Verso, 2010. Toscano’s book is a counter-history and wonderful antidote to contemporary opinion concerning possibilities for a politics of “passionate and unconditional conviction.”

(2) Gilles Deleuze, Difference and Repetition, trans. Paul Patton, London & New York: Continuum, 1997, pp. 36 - 37.

(3) See the entry “Devil” in Barbara Cassin, et al. eds., Dictionary of Untranslatables: A Philosophical Lexicon, trans. Steven Rendall, Christian Hubert, Jeffery Mehlman, Nathanael Stein and Michael Syrotinski, Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2014, pp. 211 - 215.

(4) Gilles Deleuze, Difference and Repetition, p. 38.

(5) Gilles Deleuze, Difference and Repetition, p. 36.

(6) In Deleuze and Guattari’s collaborative masterpiece A Thousand Plateaus the authors rename Deleuze’s two types of space as “smooth space” and “striated space.” See Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, trans. Brian Massumi, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1987, especially pp. 474 - 500.

(7) As cited in Lana Lopesi, “The Moral Argument: A Review of ‘Jealous Saboteurs.’”

http://www.pantograph-punch.com/post/review-jealous-saboteurs

(8) The concepts “inoperativity,” “potentiality” and “whatever being” together go to make up Giorgio Agamben’s ontological constellation. For a recent outing of these concepts see Giorgio Agamben, The Use of Bodies, trans. Adam Kotsko, Standford, California: Stanford University Press: 2016.

(9) Gilles Deleuze, “La Vie Comme une Oeuvre d’Art”, interview with Didier Eribon in Le Nouvel Observateur 1138, 4 September 1986, as cited in Eleanor Kaufman, “Madness and Repetition: The Absence of Work in Deleuze, Foucault, and Jacques Martin” in Eleanor Kaufman and Kevin Jon Heller eds., Deleuze and Guattari: New Mappings in Politics, Philosophy, and Culture, Minneapolis & London: University of Minnesota Press, 1998, p. 235. Italics added.

(10) Gilles Deleuze, Difference and Repetition, p. 261. Italics in original.

(11) Gilles Deleuze, Difference and Repetition, p. 127.

(12) Gilles Deleuze, Difference and Repetition, p. 278.

Recent Comments

Ralph Paine

Thanks Peter. Your comments concerning Francis Upritchard’s so-called “black female figures” are interesting but I’m inclined toward quite a different ...

peter madden

Hi Ralph, thank you for the essay and helping reposition a morality debate/attack. On the whole I tend to agree ...

Ralph Paine

“Year Zero: Faciality” contains many vivid descriptions and analyses drawn from many different kinds of practice—literature, psychology, painting, film, dance, ...

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 7 comments.

Comment

Andrew Paul Wood, 7:42 p.m. 12 November, 2017 #

If one is to take a Deleuzian approach, how does one ignore faciality in relation to FU's depiction of what appear to be degrees of ethnic stereotype?

Ralph Paine, 10:49 a.m. 13 November, 2017 #

D&G’s concept of faciality (the Face) is a component of a sedentary or moral distribution. Thus, simply by claiming that Francis Upritchard’s work (to some degree) utilises ethnic stereotyping you place yourself squarely within that distribution i.e. you are making a moral judgement based on model-copy resemblances, identity, etc. In contradistinction, I regard Upritchard’s work as springing from, connected to, a nomadic or ethical distribution, and thus it consists of simulacra, probe heads rather than faces, etc. In other words, her figures are singular beings, unique, exceptional.

Throughout Deleuze and Guattari’s A Thousand Plateaus we encounter many examples of what they name “abstract machines.” So much so in fact that the book could be re-titled Machine = X. If philosophy is inherently abstract, A Thousand Plateaus is a wonderful handbook on how philosophical abstraction functions, and this relayed in a manner that surpasses “any kind of mechanics,” that is to say, in a manner which ensures that philosophical abstraction and its continually variable writing machine remain immanent, co-productive, isomorphic.

The plateau or chapter titled “Year Zero: Faciality” is an account of one type of abstract machine, an account of its “nonformal” functional components and how they operate. But it’s also an account of how to dismantle the machine, how to rearrange it, and of how it might be compared and contrasted with other abstract machines. In the case of faciality the abstraction involved is said to be of an overcoding type (as contrasted with a deterritorializing type), one comprising a “black hole/white wall” system. What this system produces is “faces,” or vice versa and more generally, the Face. Thus, between black holes of subjectification and a white wall of signification, faces take shape; these sometimes appearing on the wall, sometimes in the holes. Sometimes the wall is black and the holes white; and so on: the abstract machine is a combinatory, one designed to organise and distribute faciality traits.

Ralph Paine, 10:50 a.m. 13 November, 2017 #

What then does the abstract machine of faciality overcode? Ethnology provides Deleuze and Guattari with a first and important contrasting example to that of faciality, namely, the “volume/cavity” system proper to the embodied head machine of so-called “primitive” (presignifying) societies. The social power of these societies is said to operate via modes of corporeality, animality, and vegetality, and it is precisely these modes which Deleuze and Guattari say are captured, decoded, and then overcoded by the machinism of the Face: faciality is an abstract yet real procedure of imperialism. In both despotic-State (signifying) societies and authoritarian capitalist-State (postsignifying) societies—and their “de facto” mixes—social power is said to operate via the faces of leaders, prophets, judges, teachers, bosses, lovers, police officers, mothers, fathers, etc. and hence the black hole/white wall system entails multiple staging zones: iconography, the classroom, courtroom, mass rally, TV programme, film, passional journey, family dinner table, etc. All this leads Deleuze and Guattari to the creation of richly complex theories concerning landscapes and faces, racism and faces, the face of Christ, and differences between French and Anglo-American novels.

Ralph Paine, 10:51 a.m. 13 November, 2017 #

On a line of thought including Karl Marx’s “Fragment on Machines” in Grundrisse (1973) and Samuel Butler’s three-chapter section on machines in his novel Erewhon (1872), already in Anti-Oedipus Deleuze and Guattari had announced an epoch-defining desire to assemble new ways of thinking the connections of philosophy and machine. We might conceive the abstract as the Idea, and so posit the term Idea Machine as a possible substitute, but this would get us only part of the way because the word “idea” always drifts toward the sense of an idealist disconnection between the realm of thought and the realm of the concrete, as with Platonic Ideas, which Deleuze and Guattari determine as “transcendent, universal, eternal.” Perhaps this is why they prefer to use the word “abstract,” in an effort that we learn to track things immanently, that is to say, via an alignment of the abstract within the concrete. Rather than speaking metaphorically or allegorically (i.e. this resembles that; this represents that) Deleuze and Guattari want to practise a form of analogical literalness, which means that when they speak they want to mean what they say. Or, that the way they say it is the way that it is, the way the real operates, functions, works. Consequently, and in order to maintain immanence, this way will include an extreme and excessive literalness of the abstract as such; it will take account of its own written involvement as abstraction within or “at the same level as” the concrete processes, intensities, and arrangements of which it writes.

Ralph Paine, 10:52 a.m. 13 November, 2017 #

“Year Zero: Faciality” contains many vivid descriptions and analyses drawn from many different kinds of practice—literature, psychology, painting, film, dance, philosophy, politics, ethnology, information theory—each contributing to a detailed cognitive mapping or “diagram” of where and how to track faciality traits in actual operation. But the chapter is written in such a manner as to provide a simultaneous account of the abstract-machnic workings of the Face. Or, it might be said that within the range of concrete examples we gain a profound sense of abstract processes of thought set in motion, ones which in- or sub-sist in these examples, which are said to exist. But just as the faciality machine is “independent” from, and as such does not resemble, its products and effects, the abstraction in Deleuze and Guattari’s text is not the same as the examples. Rather, the abstraction is encrypted there via a written style or manner = X concurrent not only with the complexity, gravitas, and absolute severity of the Face, but also, and alternatively, with a series of possible deterritorializations or decodings of the Face toward something new and way more joyous and celebratory; toward the assembly, that is to say, of an abstract machine productive not of faciality traits but rather of “probe heads” or “guidance devices.” Abstraction might openly condition or overcode the distribution of what exists or actually is, but it also contains different uses and conditions, this time the immanent potential of an “asubjective, asignifying, faceless” future.

peter madden, 9:22 a.m. 14 November, 2017 #

Hi Ralph, thank you for the essay and helping reposition a morality debate/attack. On the whole I tend to agree that the Lana article presented a bizarre premise akin to a desire to restrict and cleanse contemporary Art. I did however have a ? Re the Black Female Figures. First the black figures more than most seem to refer to actual living or dead people we’re as the Multi-Coloured Figures are more abstract more at a remove. The only place I could imagine them (M-CF’s) if they came to life, Pygmalion like, is a body painting fair. Everybody coos “oh you are an art work now”. Ok, the BFF's seem as if they conjure a stereotype and they appear to always be positioned sitting or undulating on the ground. In “Erect men and Undulating Women” Melanie Wilber argues that the generic depiction of women of race in illustrations of human evolution, will always depict women in positions close to the ground, always working always serving their community. That this depiction quietly serves to promote an idea of powerlessness. That the Generic Female Figure illustrated (usually as an Other) in connection with the articles on Human evolution serve to reinforce ideas of domination over female subjects. One struggles to imagine how a community in such brutal times could survive if half the community existed as such and the other half dominated them. Ok, doesn’t the positioning of the BFFs by Upritchard constitute in such a manner, a Body Organised, a Body rendered powerless, a generic body whose glance looks to the side? They have the look of being glanced down at.

Ralph Paine, 10:39 a.m. 15 November, 2017 #

Thanks Peter. Your comments concerning Francis Upritchard’s so-called “black female figures” are interesting but I’m inclined toward quite a different perspective.

There are a plethora of seated, crouched and reclining figures in Upritchard’s oeuvre—animal, nude, adorned, unadorned, semi- & fully-clothed, of n-genders, of mysterious sexuality and multi-coloured, stripy, mottled, patch-worked, furry, etc. skin and pelt—and likewise a plethora of standing, dancing etc. figures of similar description. Most of these figures appear vulnerable, somewhat helpless, weak, and this even when upright and fully clothed (e.g. “Tourist”).

What is this weakness? For me it signals a condition of virtuality, potentiality; and the extreme vulnerability each of us experiences in the event of any forced having to decide (or any forced having others decide for us) whether to be or not to be, of this or that identity, using this or that model-copy resemblance, here or there inside some preordained set of coordinates, fixes, representations, destinies.

Why not (passively?) resist all this? Why not adopt a preference for not having to decide, for remaining undecided, in potentiality, suspended, in limbo, inside some irresponsible and indeterminate zone, some space of becoming, flowing, leaping? Perhaps then I got it wrong in my essay. Perhaps nothing is “reciprocally traded” once we are inside a demonic space of becoming, nothing “given” and nothing “taken.” Perhaps there is neither measure nor quotient here.

In any case, why is it that every neurotic moralist in town wants to determine a fixed ‘n’ f_cked up place for Hannah? Take your pick: for sale in a slave market somewhere on the west coast of Africa circa 1700; locked away in some harem in 11th century Morocco; captured in full Kodachrome splendour inside the March 1973 edition of National Geographic; reclining in a red-light district street window in turn-of-the-millennium Amsterdam; posing in an Orientalist sculptor’s studio, Paris 1842; etc. For me Hannah is not an historical “black female figure.” In fact, she’s not a “black female figure” at all. Rather, she’s deep, deep purple, she’s called Hannah and she’s hanging out on Francis Upritchard’s “remarkable plane of immanence” … Thus!

In my essay I quote Upritchard speaking about the weakness of her figures and objects: “They’re very inaccurate—decorative rather than spiritual, they’re meaningless, rather than full of the power of real taonga, and they have no mana,” she says. Elsewhere she describes the figures as “holy fools.” Despite my reluctance to get Biblical on it, I think Upritchard’s words softly echo those of Paul in I Corinthians 1:27–28: “God chose what is foolish in the world to shame the wise; God chose what is weak in the world to shame the strong; God chose what is low and despised in the world, things that are not, to reduce to nothing things that are.”

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.