John Hurrell – 16 October, 2019

We see vehement disagreements that never get resolved, an aspect that fits in with the impetus behind the discussion on dialogue in Gallery Two by the group lead by Chris Braddock. Here the aim surprisingly is not about efficacy or reaching a conclusion or agreed-upon solution to a problem, but relational dynamics and the toing and froing of articulated thought.

Auckland

Brook Andrew, Christian Nyampeta, The Otolith Group, Deborah Rundle, Sriwhana Spong, Chris Braddock (with dialogue group), Sam Hamilton, Hetain Patel, Pallavi Paul, Bridget Reweti, Qiane Matata-Sipu, Kalisolaite ‘Uhila, Poata Avie Mckee, Sister and Samoa house Libraries, James Tapsell-Kururangi

How to Live Together

Curated by Balamohan Shingade

12 July - 18 October 2019

With over fifteen artists or artmaking units contributing—not all in the St Paul St Gallery or directly encounterable beyond the curator’s descriptive pitch (deliberately so)—this complex show put together by Balamohan Shingade acknowledges the tensions between individuals and the communities they are inescapably a part of. It uses a number of theoretical poles (courtesy of a couple of poets, a physicist, semiotician and some filmmakers) that pertinent ideas can revolve around, notions connected to the show’s title.

That comes from a series of posthumous lectures by Roland Barthes where he uses the writing of Zola, Mann, Gide, Defoe and Pallidius to look at the effects of different sorts of space on those that dwell within them. His examination of idiorrhythmy (an individual’s psychological and bodily needs—originally those of anchorite monks—and how these counter their obligations to small communities) is a central hub. However other (language-based) thinkers like Rabindranath Tagore, David Bohm and Ramshankar Yadav are also very present. Whilst the free but thick introductory catalogue is generously informative in its setting out of different artistic aspirations and Shingade’s organisational structure, it is not clear if the four or five ideational nexus on community / individual relations overlap, or if they are meant to.

However Shingade wants the visitor to focus on the questions of What is the intimacy we must develop to create a community? and What is the distance we must maintain to retain our solitude? The works tend to side with one or other. Occasionally both. Some works one has no access to. Others are in the gallery spaces or programmed to run at set times. Or offsite.

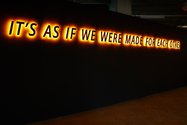

Some contributions (like Sam Hamilton’s performance videos) are one-liners, and don’t require several visits; others like Deborah Rundle’s Made For Each Other have hidden resonances and are good (in say its abbreviated title but not the longer wall text) for stimulating layered ideas about the complex relationship between self and community. A few, like The Otolith Group, disappoint, having had more interesting work in Auckland in the past (in Te Tuhi), but seem comparatively orthodox this time, producing what comes close to a typical university promotion video, albeit with some lovely community dancing, solo singing and ruminations inspired by the teachings of the legendary Tagore.

Nevertheless there is wonderful work here. In particular, there are two exceptionally interesting bodies of work that are highlights. One is Christian Nyampeta‘s multi-voiced multi-layered film, Sometimes It was Beautiful, and the other is the suite of three contemplative short films (Nayi Kheti; Shabdkosh; Long Hair, Short Ideas) by Pallavi Paul.

Nyampeta’s complex but deeply stirring project is incredible aurally, visually and ideationally. It is beautifully constructed and thought through, and it features an imaginary group of friends (they have strong differences but are very articulate, polite and forthright) sitting in a Swedish movie theatre talking about Africa, colonialism, cinema and aesthetics. This diverse but small group of politically aware artists, writers and politicians that includes Yasser Arafat, Robert Mugabe, Andrei Tarkovsky, Winnie Mandela and Sven Nykvist (the cinematographer famous for his work with Bergman) is represented by eight or so young people assertively enunciating their ideas. A salient tension is the clash between revolutionary action, the pain of the colonised, and the aesthetic pleasures of cinema as an artistic medium. There is an emotional and cerebral oscillation between opposing intellectual positions that refuses to stabilise, and an openly declared clash between the individual filmmaker and the ‘colonised’ group.

We see vehement disagreements that never get resolved, an aspect that fits in with the impetus behind the discussion on dialogue in Gallery Two by the group lead by Chris Braddock, that approach being based on the writing of physicist David Bohm who looks at the nature of certain forms of conversation and social interaction. Here the aim surprisingly is not about efficacy or reaching a conclusion or agreed-upon solution to a problem, but relational dynamics and the toing and froing of articulated thought; facilitating the process; setting up the psychological mechanisms that are ‘lubricated’ by familiarity and bonding.

Bohm’s small (stimulating and gently provocative) book On Dialogue weaves in and out of aspects of conversational participation, looking at what assumptions are involved when opposing positions seem irreconcilable—and emotions on all sides are high. In the chapter about dialogue specifically, it argues that the notion of ‘discussion’ involves the jostling of clashing opinions and is inherently competitive, whereas ‘dialogue’ is more open-ended and not about one position convincing others. Instead it focusses on collective sharing.

Bohm’s values seem to directly contradict Barthes’ title which expresses a pragmatic sentiment. Bohm in fact appears much closer to the second (out of three) set of posthumously published Barthes lectures, The Neutral, which is anti-binary.

Pallavi Paul’s three films ‘on’ the charismatic poet and social activist Ramshankar Yadav (aka Vidrohi) and his devoted abandoned wife Shanti, collectively are fascinatingly ambivalent, and because of their embracing of opposing political vectors (from several disciplines), fit in well with the above. With Vidrohi and his constructed ‘revolutionary’ persona, Paul both adores and damns, providing a ‘warts and all’ examination. The emotional and complex filmic spaces (what she calls ‘a theatre of truth’) explored by Paul include the spaces of oral poetic traditions that straddle time, the space of revolutionary discourse within the university, and the intimate space of selfless love and caring—all mixed in with apt quotations from Paul Henningsen, the Danish light designer, and Salvador Allende, the overthrown Chilean president.

Paul provides a wonderfully sympathetic foil for the brilliant carefully written Nyampeta work, but her films suffer by not being presented on larger timed projections as with three other films in the darkened Gallery One. The Paul monitors in Gallery Two are badly disrupted by the light pouring through the large streetfront window, and the sound from other nearby works (despite headphones).

In this show it is screamingly obvious that Christian Nyampeta and Pallavi Paul are incredible artists: one a superbly gifted writer and conceiver; the other a brilliant documentary maker who creates nuance through juxtaposed voices. Their thoughtful complex works can be looked at over and over. Rich, intricate and sensual commentaries.

John Hurrell

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.