Peter Dornauf – 20 February, 2020

Called 'Home Pickling', the phrase conjures wistful images of a bygone era, a more innocent time when bottles of preserves, the smell of home baking and Bing Crosby crooning Pennies from Heaven, summed up a certain ideal. This home however, cordoned off with yellow plastic tape, (the word “caution” printed boldly across it), suggests it is the scene of a crime.

Hamilton

Aaron Smith

Home Pickling

Ramp

Amanda Watson

Painting Encounters with the Land

11 February - 28 February 2020

Art, in competition with the power and lure of the mass/social media, has had to move with the times, respond, adapt and find ways to make itself heard above a perpetual clamour of voices. One of those strategies in the late twentieth century was to make art that was more politically orientated. It thereby gained a certain kudos and credibility. Relevance became the mantra.

Aaron Smith, Wintec Media Arts Masters student, has taken note and created an installation piece (exhibited at the School of Media Arts Gallery) that is saturated with social commentary. His exemplars are artists like Mike Nelson, Jessica Stockholder and Ilya Kabakov. The latter, in particular with his Soviet themed works (Capitalism, Communism and their failed utopian dreams), has helped provide Smith with his singular focus.

His critique of Western culture comes in the form of a moderately large ‘tool-shed’, painted white, (symbol of purity but also the conventional hue of many suburban domestic dwellings), complete with attractive trellis growing flowers and vegetables, (plastic ones), against the outside wall of this ‘home’, whose entrance is marked by a traditional white picket gate.

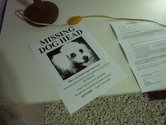

Called Home Pickling, the phrase conjures wistful images of a bygone era, a more innocent time when bottles of preserves, the smell of home baking and Bing Crosby crooning Pennies from Heaven, summed up a certain ideal. This home however, cordoned off with yellow plastic tape, (the word “caution” printed boldly across it), suggests it is the scene of a crime. The crime in question is one against humanity, perpetrated by society, or the powers that be, or the powers of individual perversity.

Inside the single tiny somewhat darkened room, we find a small desk on which is placed official notices. One is a complaint about the neighbours who decapitated the owners’ dog. The owner wants the head back. Another is an eviction notice. The only other pieces of furniture in this claustrophobic space are an empty bookcase hanging at an angle upside down and a chair with its legs sawn off. A bit of a pickle.

We are deep inside the underbelly of a fractured society amongst feral people prone to acts of indiscriminate violence. There is a hole in the wall of the room, lit red, that leads down a short narrow passage way, beyond a crouching rat, ending at a dead end where a dark red globular substance oozes down from the ceiling. Society is in meltdown. All that is missing are the sirens.

The cramped and murky quarters is a deliberate tactic by Smith to trigger psychological discomfort. Part of that ploy is to make familiar everyday objects unsettling, like a bunch of flowers teamed up with toilet rolls.

The narrative here is socio/political. From the outside, ignoring the police cordon, all looks spick and span with a garden to “mimic the beauty of rural life”. The interior, by contrast, is like a modern version of Dante’s Inferno — violent, threatening, infested, corpuscular and creepy. We could be somewhere near Lumberton, North Carolina. In the distance, faint strains of Bobby Vinton’s Blue Velvet might possibly be heard.

This interactive installation with its gate, door, room and shadowed corridor one is invited to walk down, is a timely parable, hyperbolic in tone, of contemporary suburban life at its most abject and disturbing.

Just down the road at Ramp gallery is an accompanying exhibition, Painting Encounters with the Land, by another Media Arts Masters Wintec student — Amanda Watson.

Watson has taken what one might regard as a genre that has become passé and completely played out — landscape painting — and given it fresh legs. Part of her approach is the inventive process involved in the creative treatment of her subject. It includes a direct and literal connection with the landscape itself. These are site specific works which entail wrapping the raw canvas around rocks, parts of trees or various other forms of organic matter that happen to be in the immediate vicinity.

Black ink is then applied to the large scrunched up and folded canvas while water is also judiciously added into the mix. Repositioning the canvas then takes place with a repeatable process that sees multiple wrappings take place. The results are a kind of fluid Franz Kline look that is dynamic and arresting.

The artist has provided detailed information about the sites themselves, which also act as the titles to the works. Thus, we get On the Southside in Taranaki, 18 September, 2019; Just off the track to Symes Hut on the mountain in Taranaki. One is reminded of Charles Heaphy’s Mount Egmont to the Southward in the title, but we are worlds away from that nineteenth century pictorial domain.

We also get In the Native Bush in Whaingaroa, Raglan 2018 & 2019 & from memories since 1998. The ‘memory’ part has to do with ‘touch-ups’ in her studio, augmenting the first literal encounter, aided by photographs and drawings made of the sites. She also provides ‘diary entries’ of her experiences. “April 1st, 2018, on the south side of the mountain in Taranaki: It was cold today and this weird foggy rain-but-not-rain-cloud was sitting over the valley. It was clinging to the mountain where I was working … I came here a lot as a kid with my family and friends and the familiarity and memories are comforting, but it was a little disquieting being there alone.”

These abstract landscapes are thus very personal to Watson, nostalgic journeys almost, that reconfigure the sites and transform them into geometric notations. Often multiple encounters from different sites will be employed on a single canvas to build up a layer of marks and jottings. They represent a real physical imprint of the land, a sort of literal brass rubbing in collaged fashion of the locale she knows so well, a signature of the earth, a record of time and place in cryptogram form.

The marks may be literal but they are also symbolic. Sign and substance come together here in one format and the effect is striking, fresh and audacious.

The method of the scrunched canvas recalls Miranda Parkes, but for Watson, the crumpling is only an initial process that later sees the canvas spread flat to reveal the monochromatic abutted bleedings and impressions made by ink and compressed pigment.

What these mean to the artist will be entirely different from what the viewer might take home, but that is no matter. These large canvases are a new approach to the school of landscape and abstraction, involving chance and readymade procedures, resulting in twists and turns, swoops and swerves, jagged triangulations, bulging curves and attenuated squares, rectangles and assorted blobs. Black on white speaks in a severe and minimalist language, but the outcome is striking.

Both shows, dramatically different, find their impetus, however, in a similar impulse — the search and exploration of a lost, even beautiful past.

Peter Dornauf

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.